Editor’s note: This report contains explicit language.

Goodbye, “My Cherie Amour.”

“Can You Stand the Rain”? Not anymore.

Sometimes it feels like black artists on today’s pop charts are “Heartless.”

These songs charted 50, 30, and 10 years ago on the Billboard Hot 100, which tracks the most popular music in America. Performed by Stevie Wonder, New Edition, and Kanye West, respectively, they are examples of a rich black musical tradition that explored the many meanings of love.

Today, much of the love expressed in classic songs seems as anachronistic as cassette tapes. The Hot 100 pop charts still have plenty of songs by black artists about sex, which has always been an essential thread in the emotional tapestry of music. But compared with past decades, when popular black artists consistently gave voice to humanity’s most powerful emotion, far fewer chart-topping songs today discuss love as that alchemy of need, companionship and commitment transcending the physical.

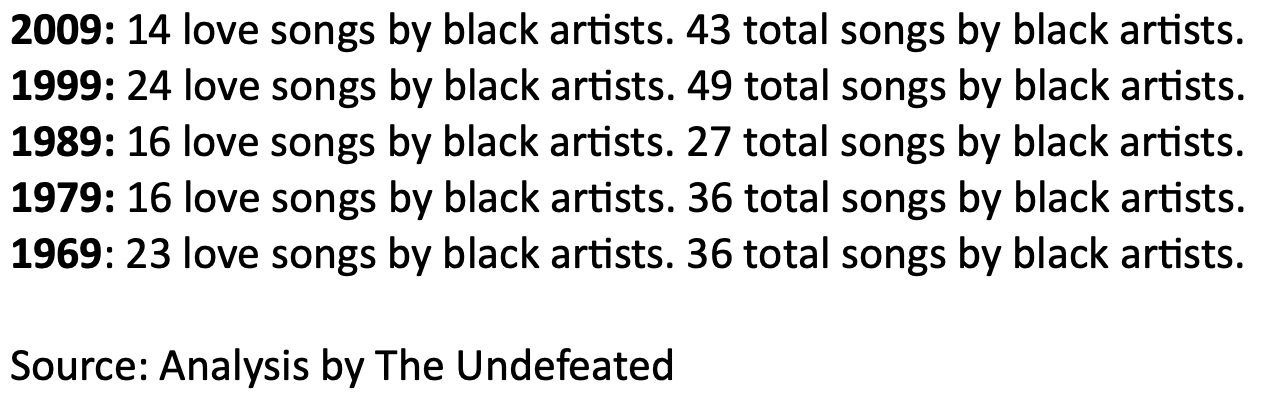

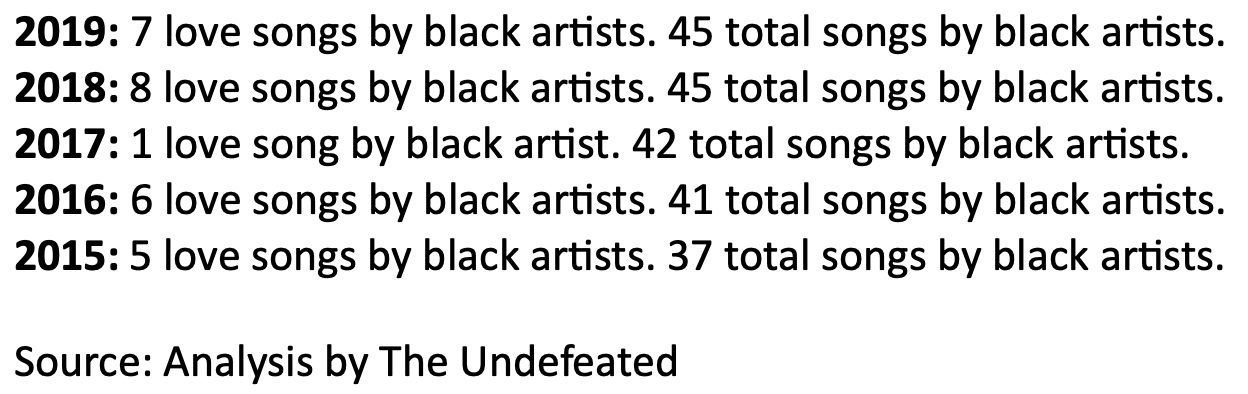

The Billboard Hot 100 measures online streaming, radio airplay and sales to determine the most popular music in America. The Undefeated analyzed year-end Hot 100 charts for the past five years, plus the year-end charts from 2009, 1999, 1989, 1979, and 1969. We counted all the songs performed by black artists, and all the love songs. We defined love songs as those dealing with attraction that is more than just sex, including love that is anticipated, fulfilled, lost, not reciprocated, or sometimes tainted by dysfunction.

Stevie Wonder, seen here on stage in Chicago July 26, 1986, is an example of black musical tradition that explored the many meanings of love.

Photo by Paul Natkin/Getty Images

The number of love songs by black artists on the Hot 100 has fallen from one or two dozen per year in decades past to an average of five per year since 2015. In 2017, there was only one black love song, Rihanna’s “Love on the Brain,” a painful lament with hints of domestic violence. The overall number of songs by black artists has increased on America’s most influential pop chart. But the proportion of black songs that are about love has fallen from two-thirds in 1969, to half in 1999, to roughly one-sixth over the past five years. Meanwhile, love songs by non-black artists remain as common as ever. (See our classification of songs on the accompanying charts.)

These numbers show a coldhearted truth: The deepest forms of love are fading out of popular black music. Or as Lil Wayne said in his 2018 hit single “Uproar”:

“What the fuck though? Where the love go?”

Yes, we are quoting profanity up in this piece. Because while there has never been more vulgarity in black pop than now, there has never been less love.

A combination of forces is pushing love out of black pop, including the ascendance of rap, the rise of streaming, the declining influence of organized religion, and the racism that constrains modern black life. The sum total makes it seem like the definition of love itself is under attack.

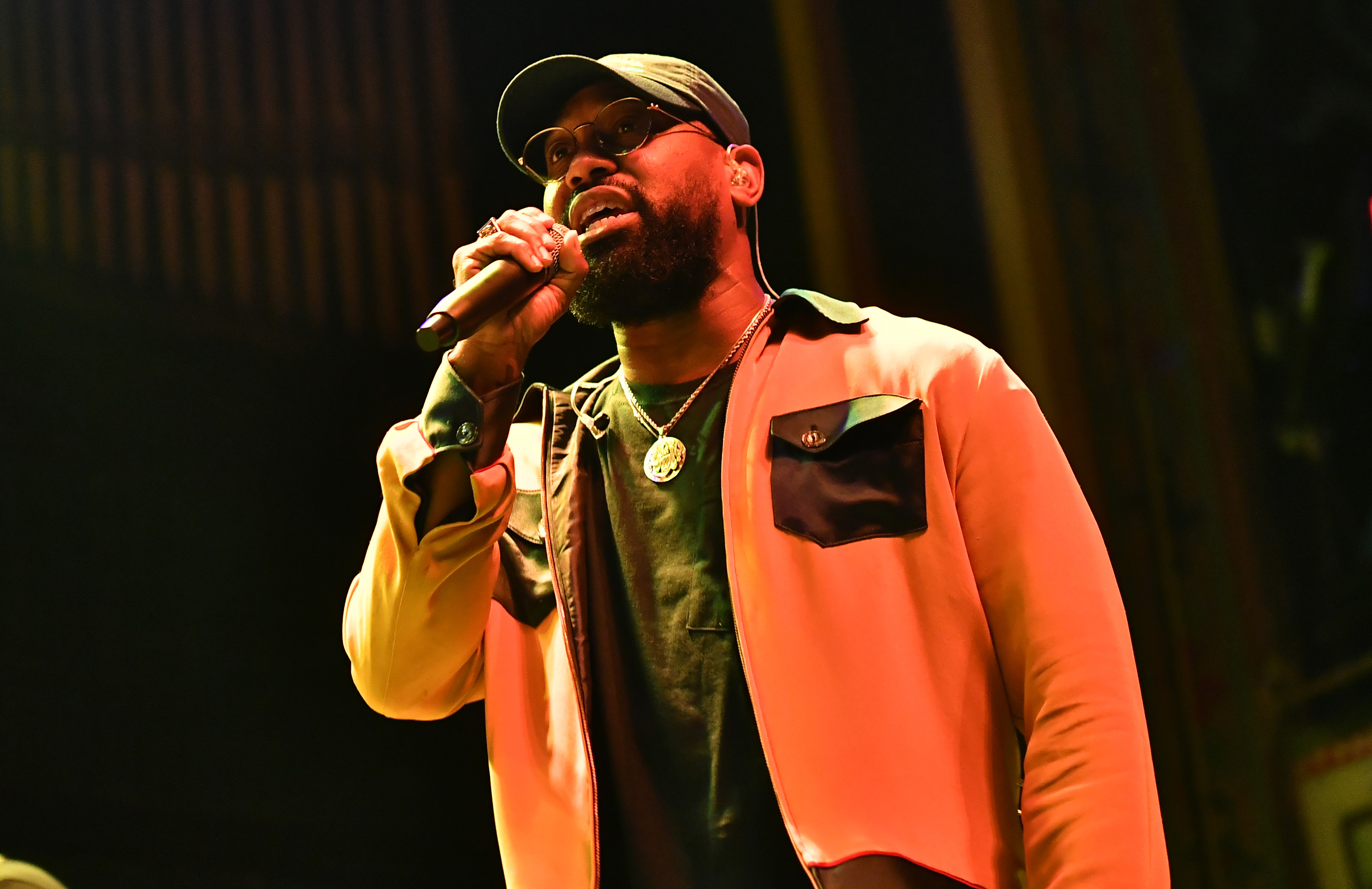

“Art reflects life. I think both men and women now are having a hard time buying into love and long-lasting love,” said rhythm and blues singer and musician PJ Morton. His catalog of love songs, including “Say So,” the 2019 Grammy winner for best R&B song, resides outside the popular mainstream.

Kendrick Lamar’s hit song “LOVE.” ranked No. 50 in the 2018 Billboard Hot 100.

Photo by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Coachella

“The music is just living out what we’re actually going through,” Morton said. “People talk about how the rules of dating these days are out the window. I think we’re just in a different time, so I think the music, as it should, reflects what’s actually going on.”

Some black love does endure on the Hot 100. Khalid’s “Talk” finished at No. 8 in 2019. Ella Mai’s “Boo’d Up” and Kendrick Lamar’s “LOVE.” both charted in 2018. But these days, black love resides mostly on Billboard’s Adult R&B chart. That’s where India.Arie’s “Steady Love” hit No. 1 in November with the refrain of, “He touches my soul and my spirit / He’s givin’ me love, so steady.” That’s also where Monica’s “Me + You” reached No. 17 last year with the declaration, “If I lost it all today, that’s OK, if you stay, I’ll take the minimum.”

India.Arie’s “Steady Love” hit No. 1 in November 2019 on Billboard’s Adult R&B chart, but it didn’t make the Hot 100 in 2019.

Photo by Aaron J. Thornton/Getty Images

“Steady Love” and “Me + You” are not pop hits. They are not the soundtrack of a new generation; they feel more like the province of a generation that still listens to radio. The Adult R&B chart is a long way from the Hot 100, which is the music industry’s holy grail of popularity and success. Twenty years ago, Monica’s “Angel of Mine” reached No. 1 on the Hot 100. The chasm between “Angel of Mine” and “Me + You” shows how far such sentiments have moved away from the mainstream – and the dance floor.

Heartbreaker: Black love on the Billboard Hot 100 From 1969 to 2009, a breakdown of four decades of songs from black artists on the year-end charts

After the love has gone: The decline in black love on the Billboard Hot 100 From 2015-2019, a breakdown of songs from black artists on the year-end charts

Young and old danced to Stevie Wonder’s “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours” (No. 3 on the Hot 100 in 1970) and Earth Wind & Fire’s “September” (No. 78 in 1979). En Vogue’s “Hold On” (No. 8 in 1990) was a club banger with sentiments such as, “trust and honesty too / must be the golden rule / you’ll feel the strength of passion in your soul … Hold on to your love.” Now dance floors throb to Lil Wayne’s “Uproar,” which peaked at No. 7 in 2018, and proclaims, “money over bitches, and above hoes / that is still my favorite love quote.”

“I’ll be loving you always,” Stevie Wonder declared on the uptempo “As” in 1976, which reached No. 36 on the pop chart. “Until the day is night and night becomes the day / until the trees and seas just up and fly away …”

Or until 2019, when the breakout hit of the year was Lizzo’s anti-commitment “Truth Hurts.” The song peaked at No. 1, finished the year at No. 13, and won the Grammy for best pop solo performance.

“I put the sing in single / Ain’t worried ‘bout a ring on my finger,” Lizzo crows on “Truth Hurts.” This is an evolution from Beyoncé’s 2009 female empowerment anthem “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It).” Even though Beyoncé’s song exults over a long-overdue breakup from an inattentive man, she is concerned about a ring on her finger. Unafraid to express this emotional need, Beyoncé commandeers the bridge and roars her ultimatum:

Your love is what I prefer, what I deserve

Here’s a man that makes me, then takes me

And delivers me to a destiny, to infinity and beyond

Pull me into your arms

Say I’m the one you want

If you don’t, you’ll be alone

And like a ghost I’ll be gone …

Ten years later, that love is almost gone. It’s reached the point where everything is not love on Everything Is Love, Beyoncé’s 2018 album with her husband, Jay-Z, where they sing more about their money and clout than marital bliss.

What happened? Or as Diana Ross asked in The Supremes’ 1964 No. 1 hit:

“Baby, baby, where did our love go?”

It would be too easy to blame rap for this loss of black love. But it’s definitely a factor.

In 1989, the year-end Hot 100 chart included only three raps among the 27 songs by black artists. The 16 love songs included ballads such as Anita Baker’s “Giving You The Best That I Got” and Natalie Cole’s “I Miss You Like Crazy.” Even R&B bad boy Bobby Brown, whose rough-edged style pioneered today’s fusion of R&B and rap, had two hit love songs that year with “Every Little Step” and “Roni.”

In 1989, the year-end Hot 100 chart included only three raps among the 27 songs by black artists. The 16 love songs included ballads such as Anita Baker’s “Giving You The Best That I Got.”

Photo by Craig Sjodin /Walt Disney Television via Getty Images

“If you believe in love and all that it can do for you,” Brown sang, “give it a chance, girl.”

In 2019, the year-end Hot 100 had 45 songs by black artists. Thirty-eight were raps. The anthem of the year was Meghan Thee Stallion’s “Hot Girl Summer,” featuring Nicki Minaj spitting, “Put this pussy on your lip, give a fuck about the dick / I get that rrr and then I rrr, grab my shit and then I dip.”

The art of rap originated among young black men in the most oppressed corners of America, where emotion or vulnerability could get you killed. Rap is still forged from aggression, competition and defiance, not tenderness, partnership or submission. Rappers do occasionally let down their guard, as in LL Cool J’s “I Need Love” in 1987 or Drake’s “Too Good” in 2016. Method Man and Mary J Blige’s 1995 remake of “I’ll Be There For You/You’re All I Need To Get By” was the ultimate in hard-body male vulnerability: “There’s a few things that’s forever, my lady / We can make war or make babies / Back when I was nothing, you made a brother feel like he was somethin’ / that’s why I’m with you to this day boo, no frontin’.”

Snoop Dogg (left) and Dr. Dre’s (right) music was so compelling, and sold so many copies that generations of artists followed their explicit rejection of the concept of love.

Photo by Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic, Inc

For every love rap, however, dozens more treat sex as a sport – or worse. Other genres also glorify sexual conquest, but a misogynistic and often X-rated ethos has drowned out most other descriptions of rap relationships. Nobody is more responsible for this than Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, whose albums of the early 1990s inked “we don’t love them hoes” into the rap vocabulary.

No disrespect to the disrespectful rhymes of Too $hort, Ice-T and Slick Rick, who were among the first rap stars to describe women as disposable. But Snoop Dogg’s and Dr. Dre’s music was so compelling, and sold so many copies, that generations of artists followed their explicit rejection of the concept of love. On Dr. Dre’s 1992 album The Chronic, he unleashes one of the greatest beats ever under a Snoop chorus of “Bitches ain’t shit but hoes and tricks / lick on these nuts and suck the dick / Get the fuck out when you’re done.” Snoop Dogg ends the song with a description of catching the woman he loves having sex with his cousin Daz – the origin story of Snoop Dogg’s ice-cold heart. (Daz remained a charter member in good standing of Snoop Dogg’s crew.)

The Chronic sequel was Snoop Dogg’s 1993 solo masterpiece Doggystyle, featuring Nate Dogg crooning, “Cause I have never met a girl / that I loved in the whole wide world” on “Ain’t No Fun (If the Homies Can’t Have None).” The timeless lead single, “Gin and Juice,” ends with Snoop Dogg drawling, “I don’t love you hoes, I’m out the door …”

“Gin and Juice” peaked at No. 8 in 1994. The Hot 100 was never the same.

Twenty-five years after “Gin and Juice,” rap has conquered pop music. A change in the way Billboard calculates Hot 100 hits helped complete the takeover.

Billboard is constantly adjusting its proprietary Hot 100 formula, which gives more weight to some forms of music consumption. As recently as 2013, sales by digital download or physical copy counted the most, followed by radio play and then streaming. That meant one purchase of a song via digital download gave it a bigger push up the Hot 100 than if the song was played once on the radio. Similarly, one radio play was more important than one stream.

Today, streaming carries the most weight, followed by radio play and then sales of downloaded or physical copies. Young people stream the most music. The music young people stream most is rap. A request to interview Billboard’s editorial director, Hannah Karp or other people at the company was declined by its publicity firm. But based on this formula, streaming is one of the main factors killing black love on the pop charts.

Tuma Basa, YouTube’s director of urban music and the former head of global rap programming at Spotify, disputed that idea, however. Basa said radio made love songs seem more popular than they actually were, because it was a safe subject that appealed to the broadest possible audience.

“If I’m a radio program director, and I play a record that alienates the listener, I lose the listener. On a streaming playlist, or on YouTube, if someone doesn’t like a song, they skip the song. They don’t get off the platform or the playlist,” said Basa, who used to curate Spotify’s influential Rap Caviar playlist.

“So on platforms like YouTube or playlists, we can take different kinds of risks because we don’t lose people completely. The program director at a radio station has to focus on things that relate to a large amount of people. A lot of people relate to love or heartbreak. That subject matter is very safe.”

The lack of black love in today’s popular music, Basa said, “is more of a reflection of what people want to hear than before.”

There is truth to that idea, but it ignores the power of the music industry, which is dominated by predominately white-run, publicly traded corporations, to influence a song’s popularity. Most of the audience for the black music on the Hot 100 also is white. At a minimum, these corporations have created a financial incentive for black artists seeking pop stardom to produce loveless music.

By this point, the industry and the audience are both addicted to this music. So what does that mean?

If you want to know what’s happening with black folk, Nelson George wrote in his 1988 book The Death of Rhythm and Blues, just listen to our music.

Our most popular music today says we no longer understand the meaning of love.

Khalid’s single “Location” was a Billboard Hot 100 hit in 2016. Jason King, a musician and New York University professor who teaches pop music history, said “Location” is a love song for millennials living in a world of dating apps and Instagram DMs.

Andrew Lipovsky/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

“The definition of love is getting contorted and twisted and perverted,” said the 30-year-old rapper Dee-1, whose latest album is titled God and Girls. “There’s a lot of confusion in my generation, and the generation below me, as to what the goal is when it comes to relationships and love. We hear these terms, but people don’t actually know what’s being sought. I feel like marriage is the goal of being in a relationship, and I don’t think people are hearing that narrative enough.

“It’s tough for a young black man or woman to have an accurate definition of love today,” said Dee-1, “especially when they’re listening to popular music and the way society as a whole approaches these topics.”

Take R&B star Khalid’s debut single, “Location,” a Hot 100 hit in 2016. Khalid describes a new acquaintance he wants to know better, and asks to meet up: “Just give me the vibe to slide in / Oh, I might make you mine by the night.” In the video, he follows a pin on his phone screen until it leads him to a party, then through a bedroom door, and finally to the woman lying on a bed.

Khalid, who was 18 when the song dropped, described it to Complex as “a story of young love. … just a story of searching for something that we all want in life no matter who we are and that’s a real genuine lover, but it doesn’t come easy.”

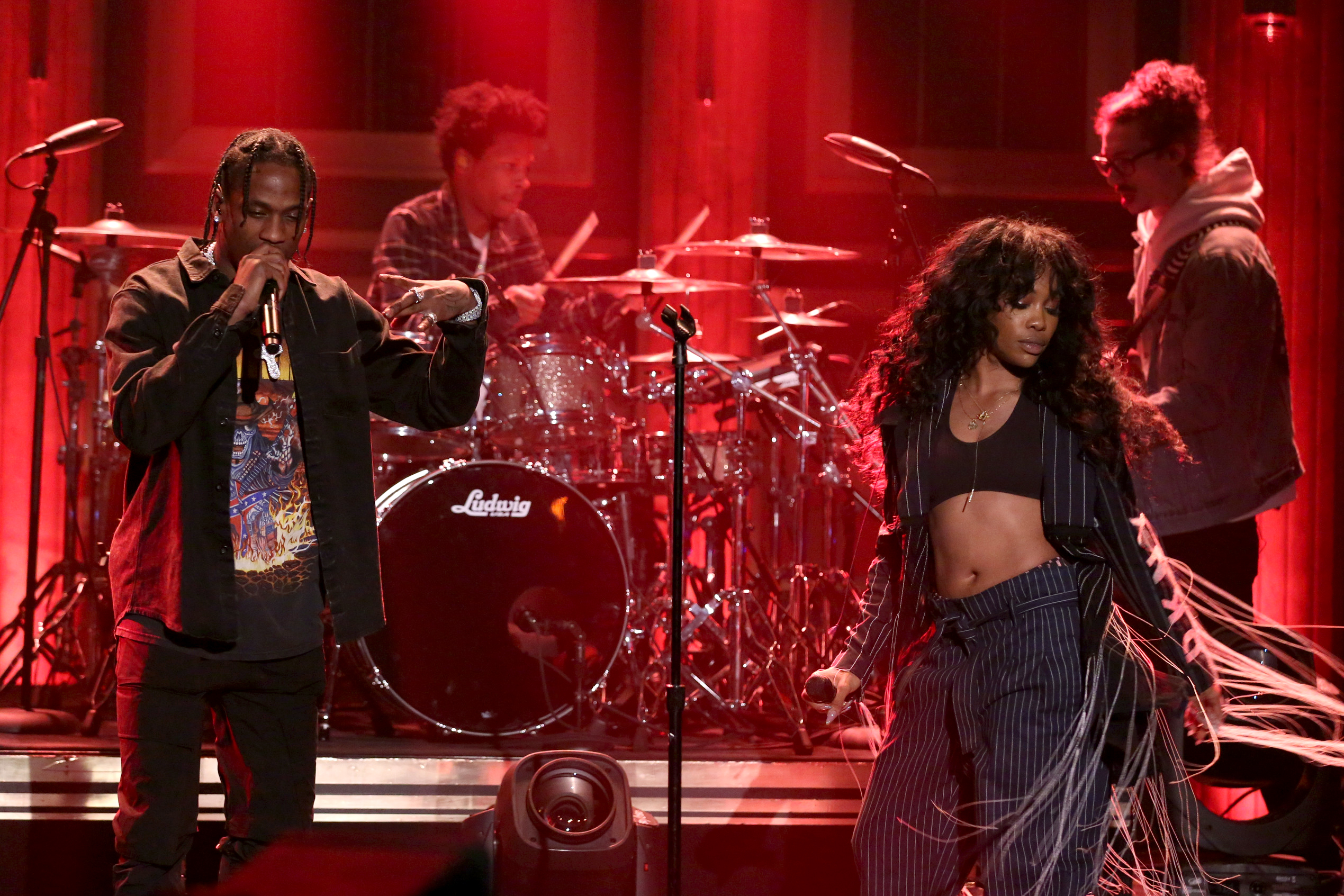

Travis Scott (left) and SZA’s (right) hit song “Love Galore” reached No. 80 on the Hot 100 in 2017.

Andrew Lipovsky/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images

Jason King, a musician and New York University professor who teaches pop music history, said “Location” is a love song for millennials living in a world of dating apps and Instagram DMs. “Millennials in particular are conflating sex, love and intimacy in ways that were not as easily conflatable in the past,” King said.

Like in SZA and Travis Scott’s recent Hot 100 hit, “Love Galore.”

“I don’t love these niggas / I dust off these niggas / Do it for fun / Don’t take it personal,” SZA sings. In a commentary on the Genius lyrics site, SZA said, “We was kicking it for the summer. It’s not that deep … ‘Why are you bothering me? You literally don’t want to do anything but smash.’”

At the end of the “Love Galore” video, SZA ties Scott to a bed, then leaves. A psychopathic woman with a pickax enters their love chamber.

Blood splatters the ceiling.

Black music has always been the canary in America’s coal mine. Ever since we sang of deliverance from bondage, our music has expressed truths that were only later accepted as real.

Beneath all the progress of the past 50 years is a deep reservoir of trauma – obtaining equal rights later revealed to be illusory, the crack epidemic and the government’s attendant War on Black Neighborhoods, mass incarceration, a tripling of the percentage of black children born to unmarried parents, the election of a black president and its backlash, videotaped proof of police killings …

“Love is a very different thing in an age of damage,” said King. “In the last 10 to 15 years, you’ve seen black musicians in R&B and hip-hop still exploring issues of intimacy, but doing it through the lens of damage.”

“Tainted love” songs, where love crushes instead of comforts, frequent the recent Billboard Hot 100, including Cardi B’s “Be Careful.”

ANGELA WEISS/AFP via Getty Images

“The biggest figures that we have in black music today are not really love figures, at least not compared to a Smokey Robinson, Phoebe Snow, or Roberta Flack or any of those people back in the day,” he said. “Today you have Drake with ‘Fake Love’ or ‘Passionfruit,’ where it’s like, how do I have trust in a relationship? Or The Weeknd, who’s all about projecting this kind of performative damage. Or Cardi B, who does rap a lot about relationships, but there’s a lot of cynicism there.”

“Tainted love” songs, where love crushes instead of comforts, frequent the recent Hot 100: Cardi’s “Be Careful,” Juice WRLD’s “Lucid Dreams,” Lil Baby’s “Close Friends,” XXXtentacion’s “SAD!”

“Aretha Franklin was doing tainted love too,” King said. “But she also knew how to exalt a kind of all encompassing love with a capital L. I think younger artists are not that interested in that notion, which also has to do with the church – the love of Jesus being transferred, literally, into soul music. That’s what soul music was: Taking your love for Jesus and applying it to secular matters.”

Morton, the R&B singer, said more black people used to attend church every Sunday, “whether you were a heathen or a saint. There was a certain community there and a certain soul connected to that. I believe that was a big part of our soul songs, our R&B songs, our love songs.

“I just feel like that is a piece we don’t have anymore – a message of God’s love.”

“God is love,” the Bible says. Black American music began with this love. We asked Him, in our African call-and-response tradition, for strength and freedom. These “Negro spirituals” begat the blues, which begat jazz, rock ’n’ roll, R&B, and rap.

“The blues impulse transferred .. . containing a race, and its expression,” Amiri Baraka wrote in his seminal 1966 essay The Changing Same (R&B and New Black Music). “Through its many changes, it remained the exact representation of The Black Man In The West.”

The Billboard Hot 100 is not an exact representation of black people in America. It’s just one snapshot, although a particularly profitable one. Black artists are still making love songs outside of that business model. We just have to look for them.

Singer PJ Morton, whose hit “Say So” won a 2019 Grammy for best R&B song, on the current status of love songs: “Art reflects life. I think both men and women now are having a hard time buying into love and long-lasting love.”

Photo by Paras Griffin/Getty Images

Ironically, although streaming has pushed black love to the margins of the recording industry, it also made it easier to hear. Radio play is no longer necessary. King, the NYU professor, identified a “quiet stream” of black artists such as Jorja Smith, dvsn and Amber Mark, who receive relatively little commercial attention, but have brought a deep love aesthetic into today’s music.

A.D. Johnson, a music licensing executive for Universal Music Group/Universal Production Music, also is a DJ who curates a love songs playlist. He cited Morton’s “First Began” as a great under-the-radar love song. “No disrespect to someone like Chris Brown, who is amazing and talented,” Johnson said, “but what if PJ Morton had a Chris Brown budget?”

Morton isn’t holding his breath. He’s too busy. He just returned from several sold-out European shows, and is currently on 14-city American tour of small and medium-sized venues.

“What I’ve learned and seen is the hunger for what I do,” Morton said. “How it touches people and how it’s connected with people who still do want that. I just feel like now, it’s more of a mission.

“I do believe there are cycles, you know?” he said. “I don’t think the songs that are popular today should disappear, but I do believe the percentages will shift. I think people will get tired of not having any depth. They’ll get tired of all that candy. At some point, they’ll get a stomachache and want some real food.

“When people are ready, they’ll find that love is there, just waiting.”

Because love endures. Even when suffering from today’s collision of commerce, history and technology, love remains.

Like Bobby “Blue” Bland, the Isley Brothers, Marvin Gaye, Ten City and Bobby Brown said:

That’s the way love is.