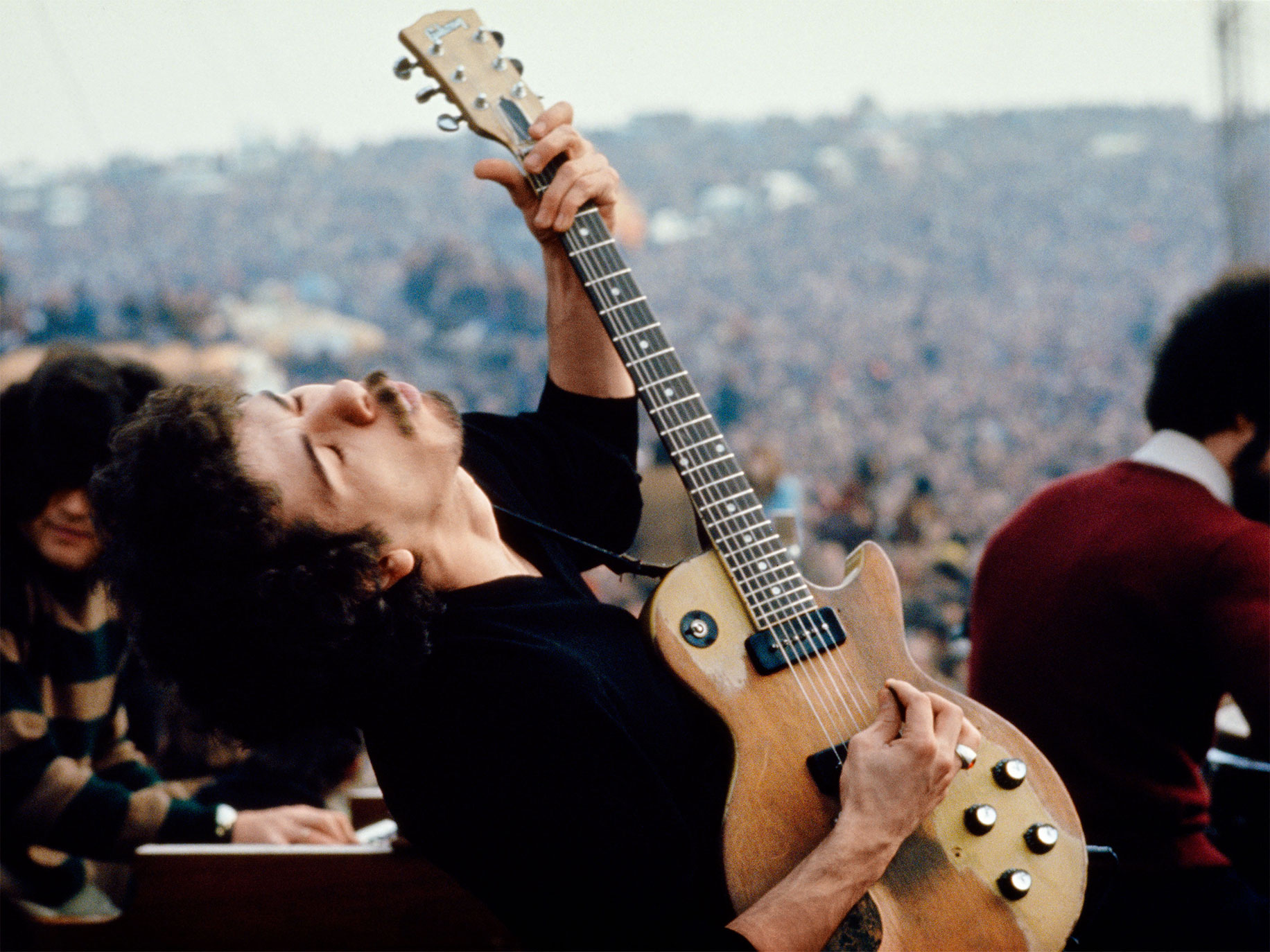

Jim Marshall’s genius lay in capturing images whose stories stretch far beyond their frames. Jimi Hendrix smiling down at his flame-engulfed guitar during the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival defines not only that iconic artist but also the legendary festival and the gilded age of rock itself. “He called himself ‘a reporter with a camera,’ ” says Marshall’s longtime assistant Amelia Davis. Davis worked with Marshall for 13 years before he passed away in 2010, leaving his estate to her.

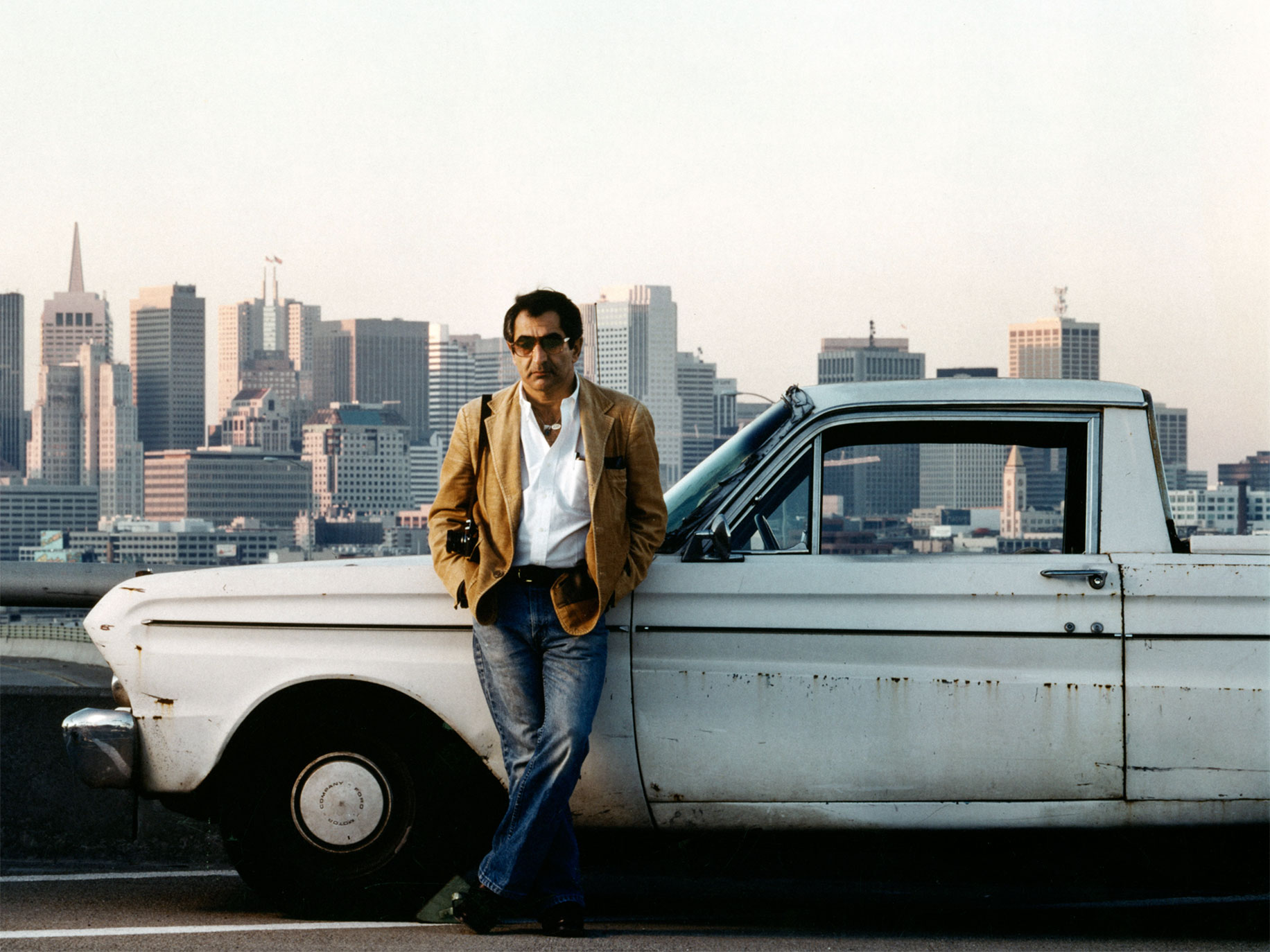

“He always said that his children were his photographs. His life was his photography,” says Davis. Marshall was self-taught; he bought his first Leica camera in 1959, when he started taking pictures of jazz musicians in San Francisco’s North Beach. He used an inconspicuous, easy-to-carry camera with a quiet shutter as he embedded himself in his subjects’ lives and they forgot he was there.

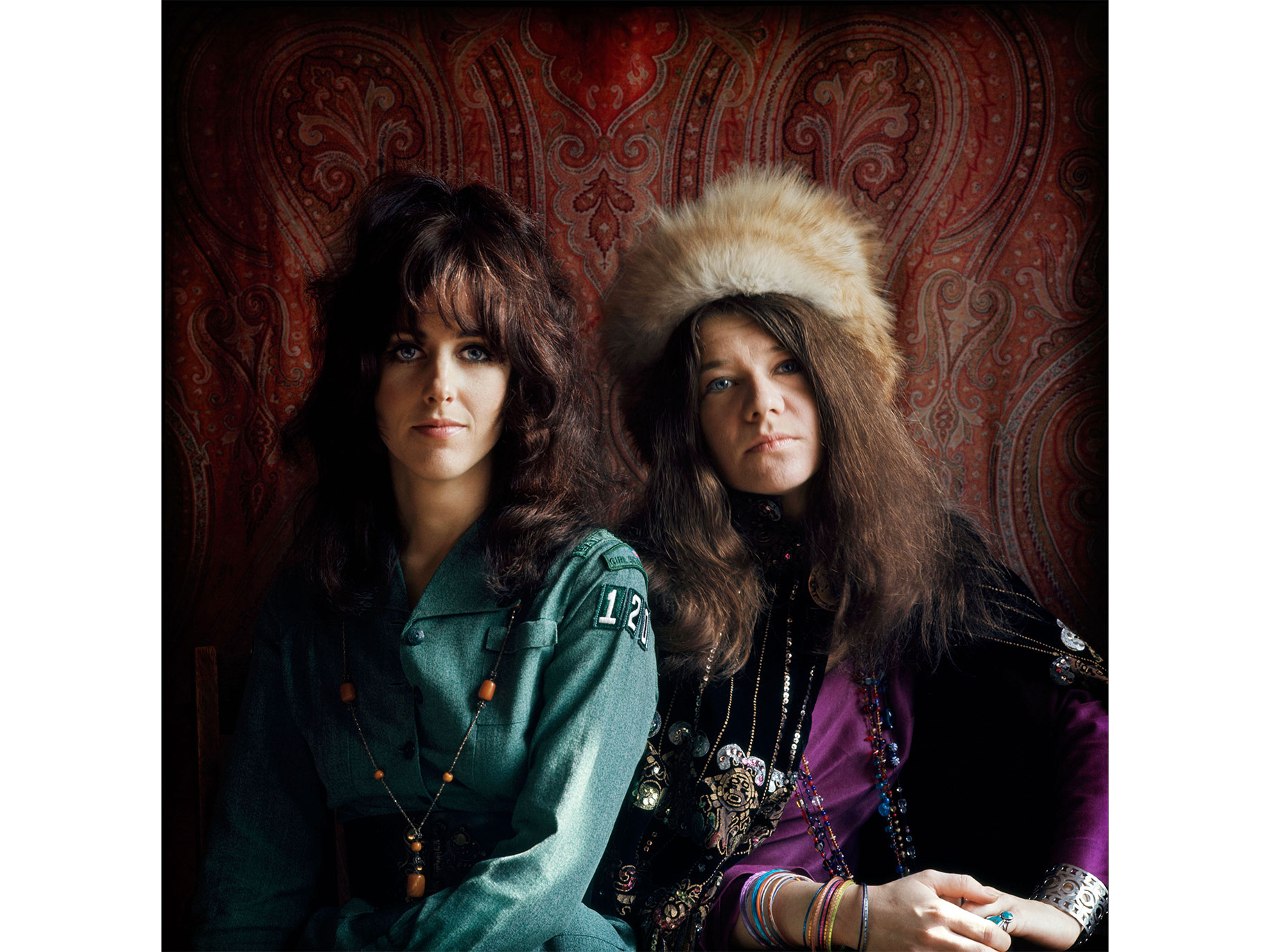

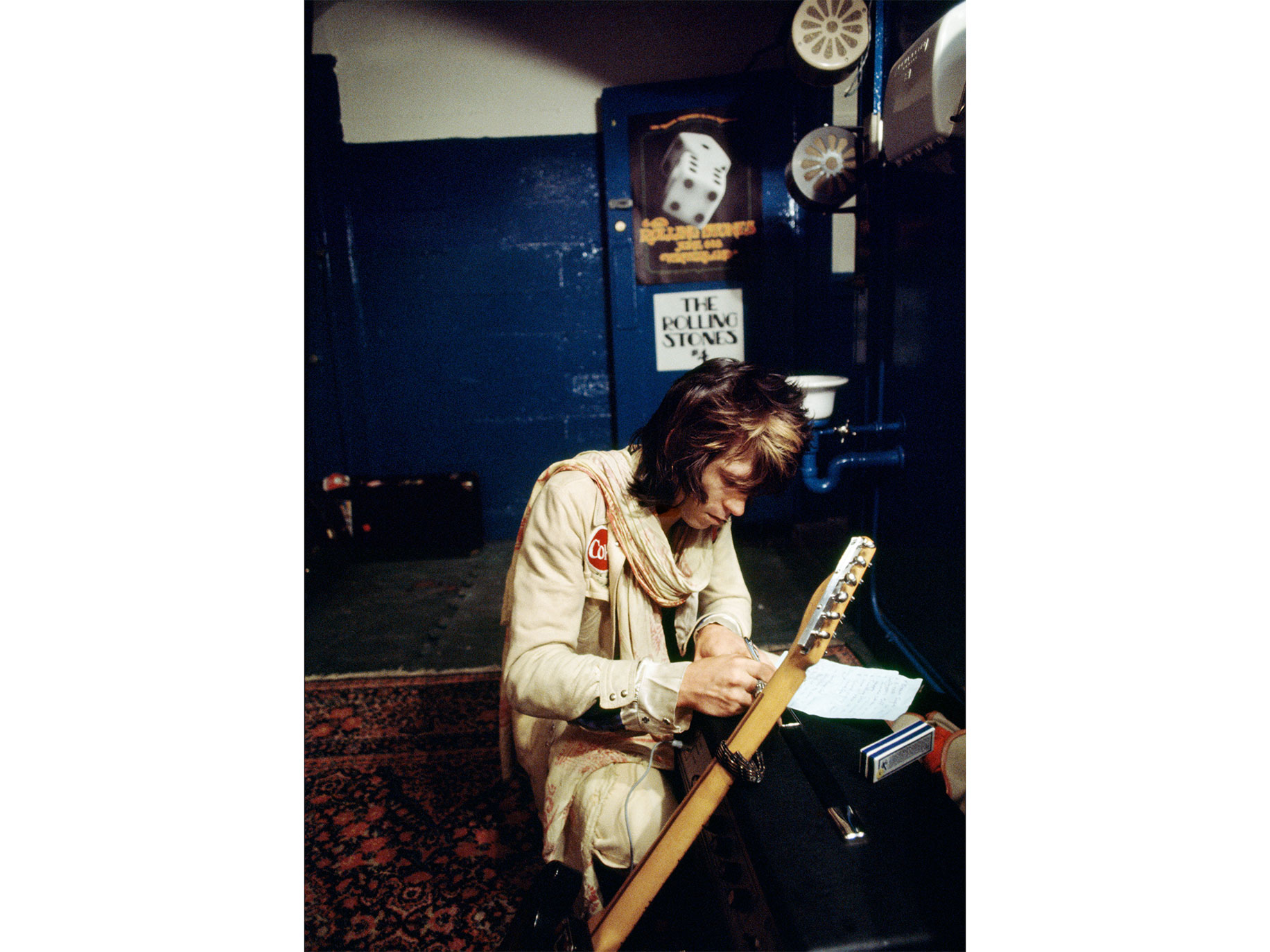

On an early-1970s tour with the raging Rolling Stones or in the New York apartment of a relaxed Thelonious Monk mugging with his family, Marshall caught the unfiltered personae of the complex people he shot. “Their guards were down, and they were not really posing,” Davis says. “Not only was he able to capture these musicians at the height of what they were doing as these gods of music, but he was also able to capture them as human beings backstage.”

Marshall also had a knack for being in the right place at the right time, whether it was hanging out in Greenwich Village with a young Bob Dylan, venturing onstage at Woodstock and Altamont, visiting with a meditative John Coltrane, or chasing the Beatles across the infield at Candlestick Park during their last paid concert.

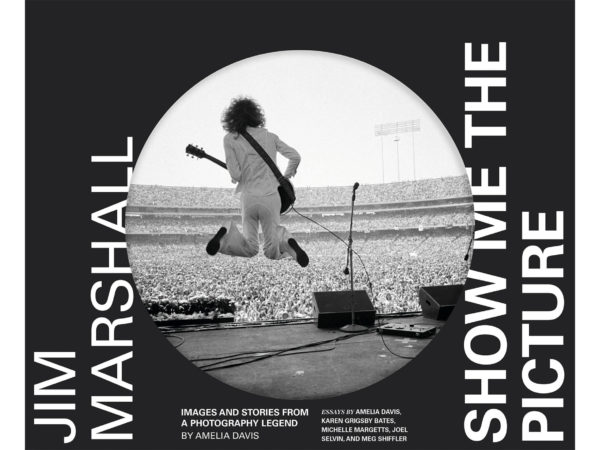

Davis has curated several volumes of Marshall’s work. The latest, Jim Marshall: Show Me the Picture, demonstrates that he was not just a great music photographer; he was also an astute chronicler of his time. His images of early civil rights events in the South, Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s, and marginalized people wherever he saw them reveal their subjects’ humanity—and Marshall’s wide-ranging curiosity. “Jim was trying to document what was going on,” Davis says, “everything he saw.”

©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY

©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY ©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY

©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY ©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY

©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY ©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY

©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY ©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY

©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY ©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY

©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY ©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY

©JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY