CultureMusic Indie rock Rock music

Singer and guitarist Stephen Malkmus became one of the most respected voices in modern rock when his band Pavement arrived on the scene 30 years ago. The band recorded a number of critically-acclaimed records such as Slanted and Enchanted (1992), Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain (1994) and Brighten the Corners (1997)—that have often appeared on music critics’ “best albums” lists. While Malkmus is hesitant to talk about his legacy today, his influence can be heard across the current crop of indie rock artists, whether it’s the frantic pop-punk of musicians such as Jeff Rosenstock or the groove-oriented, swaggering indie rock of a band like Wolf Parade.

After Pavement went on hiatus in 1999, Malkmus entered the second phase in his career as the leader of the Jicks, who have recorded seven well-received albums. Of late, he has branched out of the indie rock genre, sans the Jicks, starting with 2019’s electronic-dominated Groove Denied. Now he is making another stylistic and radical musical departure with Traditional Techniques, a ’60s-styled folk album due out on March 6. Traditional Techniques invokes both the simplicity of storytelling troubadours like Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, but veers into psychedelia reminiscent of The Doors. Nonetheless, this is a record for a 2020 audience.

Malkmus, 53, will of course tour to support Traditional Techniques in North America, starting on March 31 in Minneapolis. But here’s some big news: He will also reunite with Pavement in June at the Primavera Sound festival in Spain and Portugal. Malkmus talked all about it with Newsweek. Edited Excerpts:

What inspired you to make a folk album?

I was sort of curious to see what my songs put through that prism would be. That wish combined with the possibility to do it, because Chris Funk [of indie rock band The Decemberists], who helped organize it, offered me the relative[ly] easy ability to throw together a band to make it happen in my hometown. I would say those two things: opportunity and desire.

What artists influenced this album?

Song to song, I pictured myself as kind of a Gordon Lightfoot-style existential troubadour—a little bit melancholy and singing in a lower register with a bit more gravitas than some things I do and quieter. Certain voices or styles of singing would pop up in my head. I would sound like Lou Reed for a second, or folky things like Bert Jansch—Bob Dylan even. A lot of ’60s guys.

Is there a thematic thread that runs through the album lyrically? Or do you see them as individual songs?

It’s hard for me to be the arbiter of that. I don’t think that way necessarily. When I said I was the existential troubadour, which is kind of ridiculous, I don’t know what to say. If you notice something, tell me, and I’ll probably agree.

I’m always curious if an artist thinks about an album as a whole when they’re writing it, or if they’re just going song to song.

I would want to use a language that was of our time and not completely retro. At times, if it’s sounding like it was made on a porch or in an incense-drenched Afghan-carpet studio, I don’t think I want the lyrics to just take you back to incense and peppermints. I used some of my own modern jargon and ideas updating some of our neuroses from today [laughs].

My favorite song on the album is “The Greatest Own in Legal History.” Can you tell me more about writing and recording that song?

Originally I imagined it as one of [’70s power pop band] Big Star’s softer ballads in terms of melody, but then it slowed down—and then I was maybe vocally in a Bob Dylan sound. I came up with the tagline: I was on a “greatest own” of something. When I got to “Legal History,” I was like, “Okay, this is going to be a slightly self-satisfied but earnest public defense lawyer.” He’s just going to be pumping up his young client to let him know that he sympathizes, and that he’s there in his corner and he’s going to save him. It starts to write itself. You get a few cinematic images in your head and off to the races.

Songs like “Shadowbanned” and “Brainwashed” lyrically have a modern sensibility, but there’s also a classic timeless sense stemming from the folk presentation. Do you try to write more timelessly or for the moment?

A song like “Shadowbanned” is totally of the moment to the point of some of the jargon and thoughts in there will be thought of as silly, internet-y, cringe maybe [laughs]. The music is going in a way that’s not that. They’re pretty solid formats for singing whatever you want in a way. One thing I had to do was make the songs pretty simple by some standards, because everyone had to learn the songs on the fly. Hopefully, it does create a different feel than roots rock. If people are looking for that when they go to their playlist, “give me soft rock,” it’s going to be a little bit of cognitive dissonance. I could’ve used that, too, in a song.

You made three albums in the last three years: the indie rock Sparkle Hard, the electronic-oriented Groove Denied, and now the folk-inspired Traditional Techniques. How conscious are you of genre when making a record? And do you see yourself experimenting with other genres in the future?

In this case, I was pretty aware. The last 17 years I’ve just been making records, and they identify as indie due to the audience and the state of electric guitar music that’s not Nickelback or metal. Even though it’s probably closer to some rock ‘n’ roll that was not indie when it was first made, it identifies as that. As far as the future, it’s open. I don’t think I’m going to try to make a Nashville country-sounding modern record or some genre that’s outside of my signifiers, but there’s a way to do it, just like the Traditional Techniques that’s a fresh approach.

So we can’t expect a gangster rap or death metal record?

I can’t rap. I’ve tried to rap—that boat just sinks when I try it. I don’t have the voice for it. And, metal—I’m not really good at playing fast, and I don’t love fast music.

You’ve worked pretty consistently with the Jicks since the start of the 2000s. What was it like to record an album with a different set of musicians?

It’s different. I think I develop a certain working style with people, which there’s a lot of benefits from that and concepts of loyalty, teamwork and a shared existence. Those are the things with the Jicks that I have. But when you play with somebody else, inevitably, you get more surprises. It gives me a chance to play a different role. Relinquishing some control, that was pretty cool.

Pavement is marking its 30th anniversary with appearances at the Primavera Sound festivals. How do you view your influence—and Pavement’s influence—on indie rock and pop music at large?

It’s hard to reflect on it without sounding like you’re really great. All I can say is I’m really happy that people want to hear those songs. I’m going to make every effort to make it period correct. Pavement’s going to try for a ’90s sound and do those songs as they were then.

Are there any new artists that you feel are an extension of what Pavement did?

I like all kinds of genres.If we’re talking just guitar music, it’s hard for me to want to put that upon another group or something though. Of course, there have been some bands that have been mentioned in the same breath—like Parquet Courts, and I like them a lot. They’re doing their own thing, and they probably don’t want to even hear that. I guess I’m a little careful to say what we influenced: like Real Estate doesn’t sound like Pavement. They’re good. Snail Mail. Everyone’s got a distinct voice, but I know what you mean.

Traditional Techniques comes out March 6 on Matador Records.

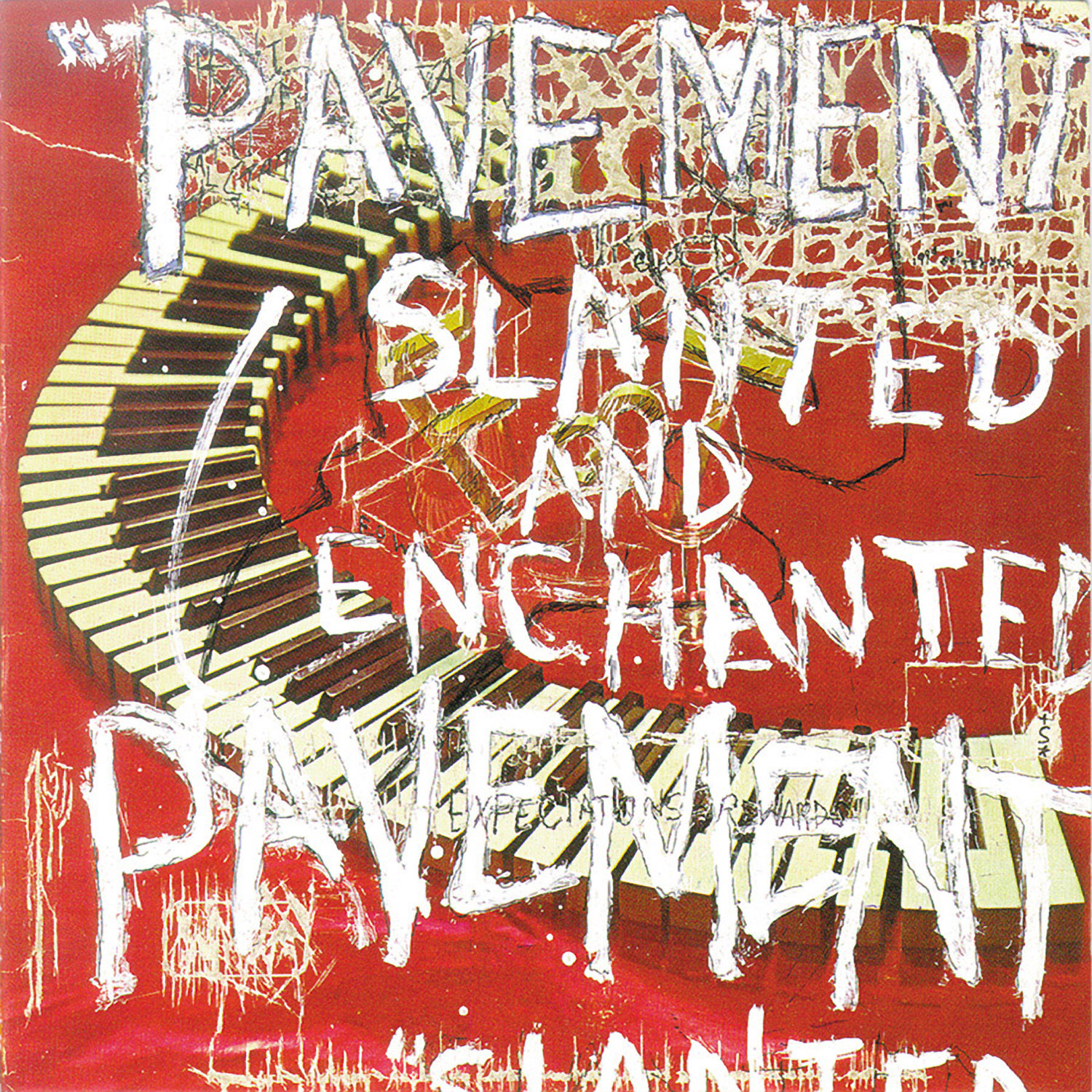

Slanted and Enchanted (1992)

Pavement’s 1992 debut is also often mentioned as a ’90s classic. The album is a little rougher around the edges than the band’s later work, but tracks like “Summer Babe” and “Zurich Is Stained” are clear predecessors to what Pavement would accomplish throughout the decade.

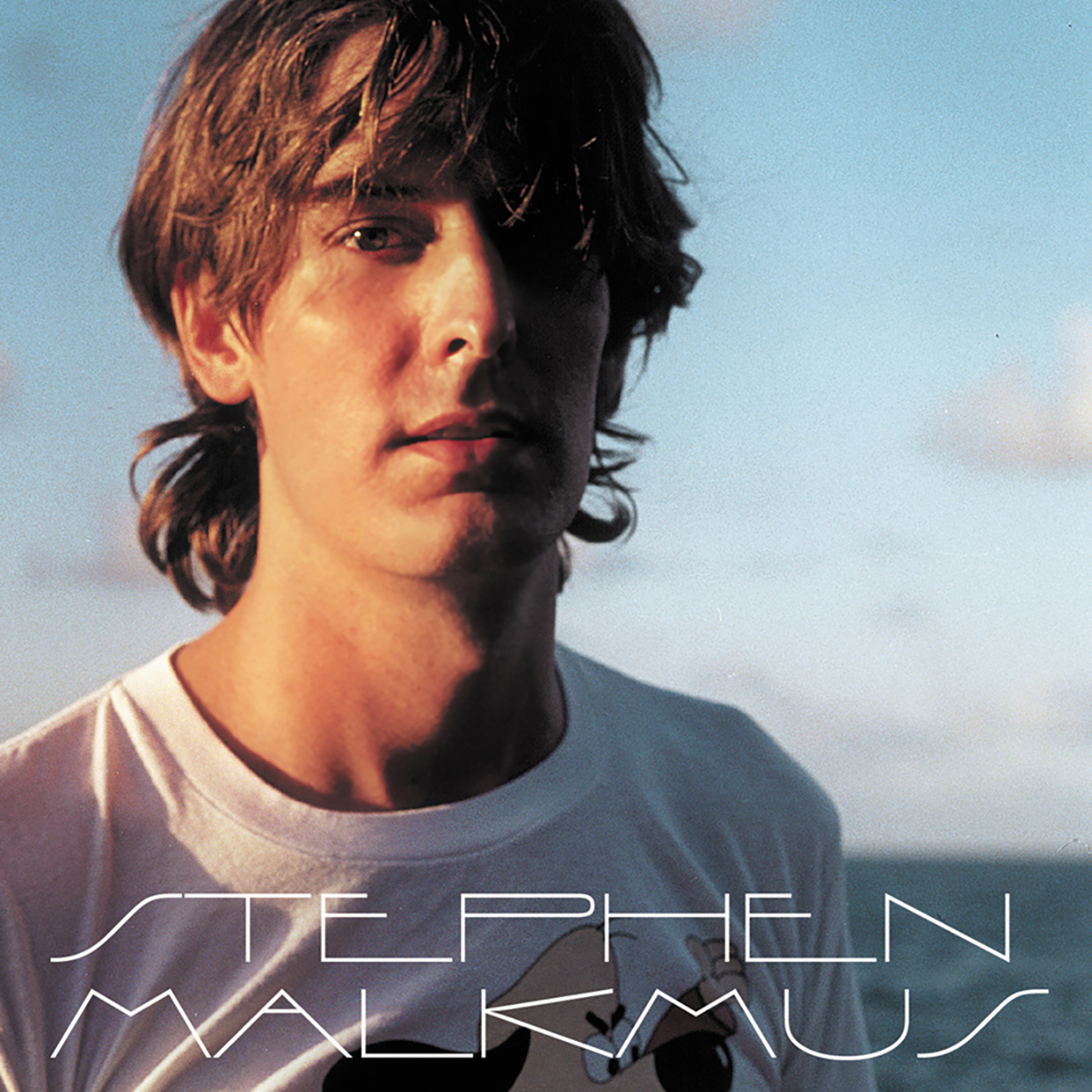

Stephen Malkmus (2001)

The singer’s self-titled solo debut, released two years after Pavement’s dissolution, is some of Malkmus’ best work. The album saw him writing songs that both resembled commercial jingles such as “Phantasies” and thoughtful ballads, like the gospel-tinged “Vague Space.”

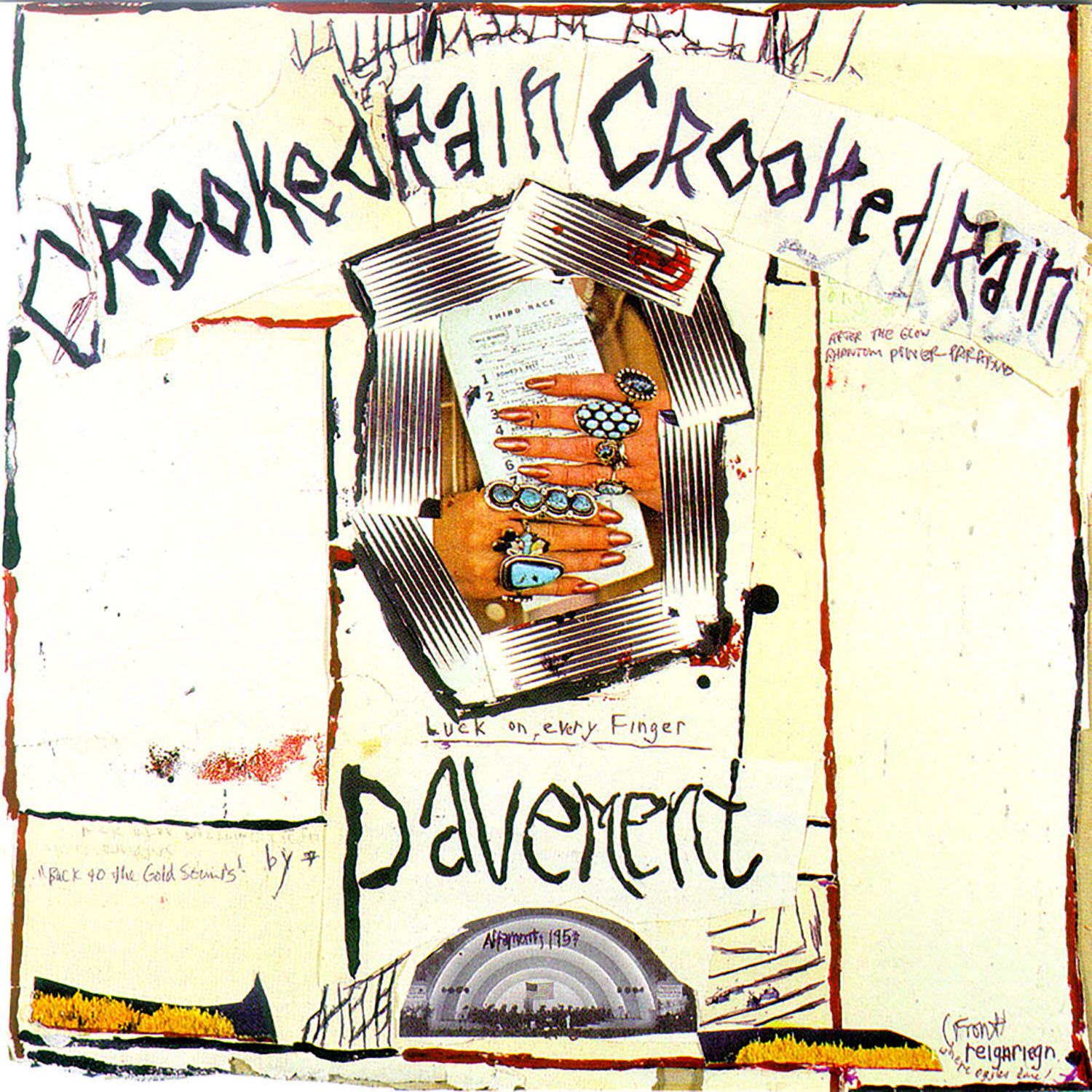

Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain (1994)

Pavement’s sophomore record, oft-regarded as their best, is an indie classic. Tracks like “Cut Your Hair” and “Gold Soundz” are essential, decade-defining tracks of the ’90s, combining catchy, garage-rock with smart, often self-aware lyrics. The album’s 2004 reissue also has lesser-known gems like “Nail Clinic.”

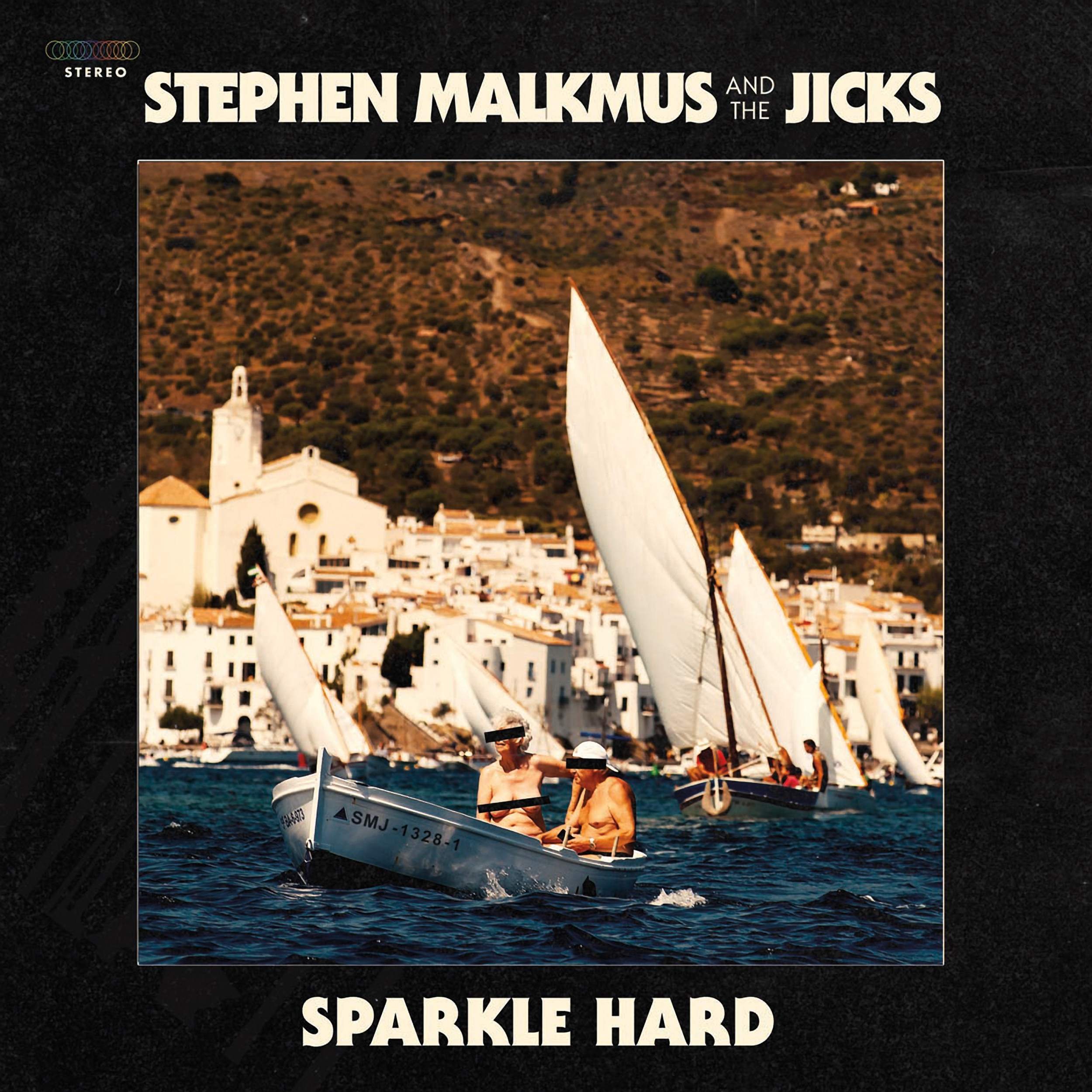

Sparkle Hard (2018)

Malkmus’ most recent album with the Jicks has the same infectious songwriting that one would expect from the singer-songwriter, but he pushes the envelope more than other releases with the band—as with directly political tracks like “Bike Lane” and “Shiggy”—and country tinged-tracks like “Refute,” featuring Kim Gordon.