What’s the most significant Philadelphia music landmark that needs to be saved?

Last month, Preserve Pennsylvania announced that the John Coltrane house in Strawberry Mansion is under threat.

Related stories

- ‘Philadelphia is the city that sleeps on itself’: How a Brewerytown record store owner is shining a light on our overlooked musical past

- ‘Are you sure it’s Sun Ra?’: Rare recording by the Philly jazz giant at Haverford College finally sees the light of day

- Concerts in Philadelphia, from Billie Eilish to Celine Dion to Hoagie Nation

That’s a big one. The importance of the site where the jazz great composed his 1960 album Giant Steps was stressed in an Inquirer opinion piece by Faye Anderson headlined “Preserving John Coltrane’s house can help save Philly’s soul.”

But when it comes to protecting the places where history was made, another imperiled building is unparalleled in its importance to the sophisticated music for which the city became known in the 1960s and 1970s. Its name is synonymous with Philly soul.

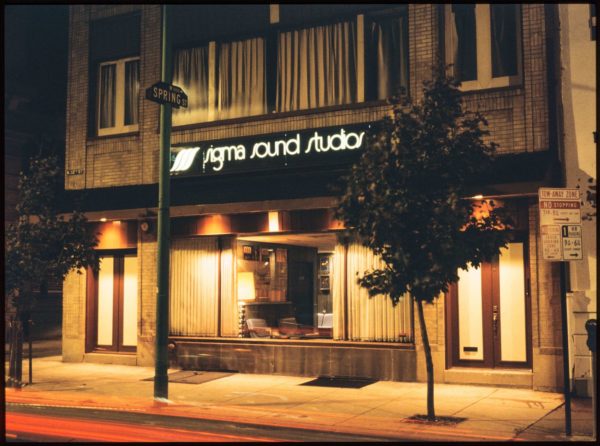

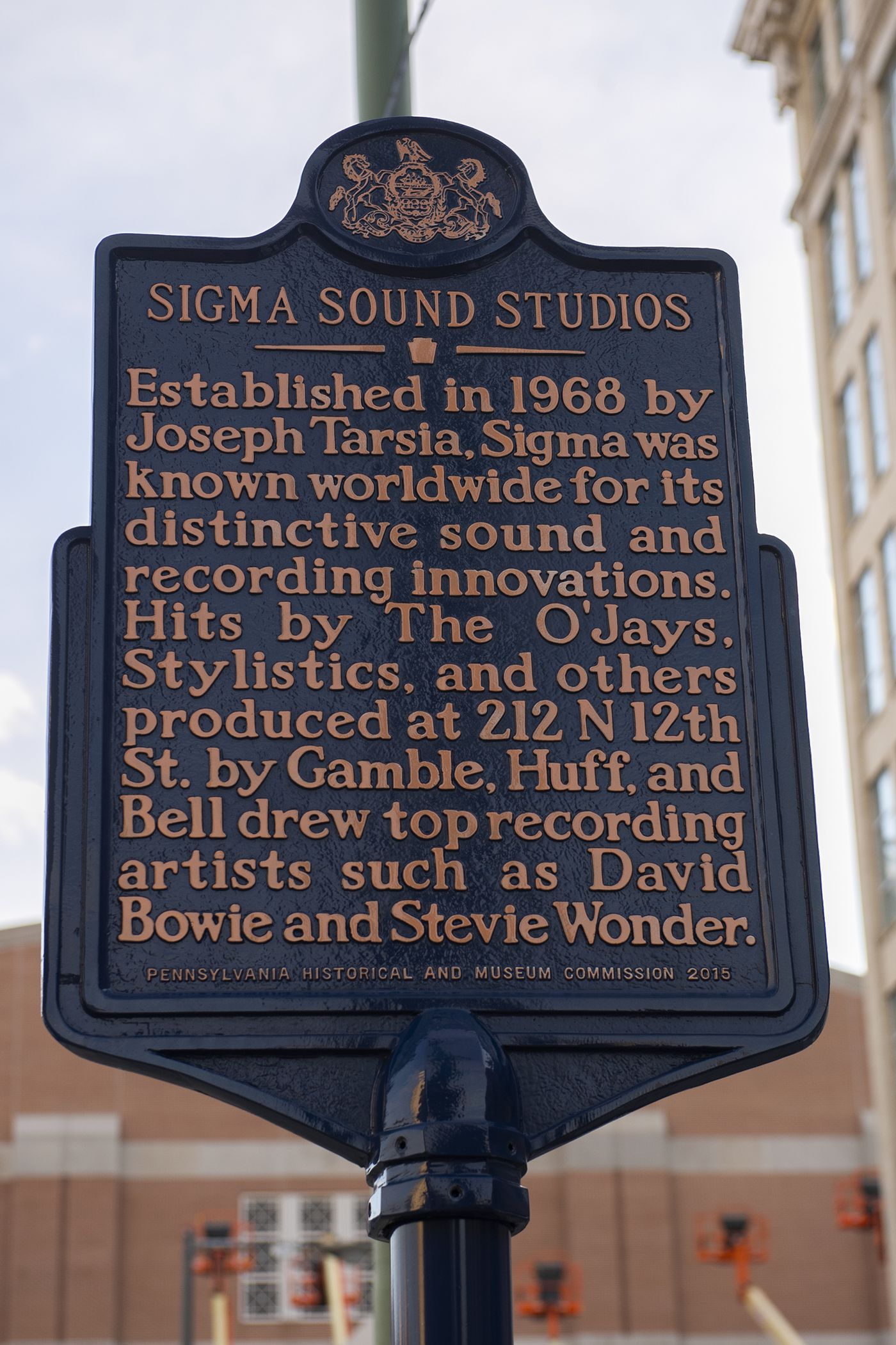

That would be Sigma Sound Studios, the recording facility on North 12th Street that engineer Joe Tarsia founded in 1968.

There, producers and songwriters Kenny Gamble, Leon Huff, and Thom Bell — “The Mighty Three” — oversaw the careers of the O’Jays, Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes, the Stylistics, and more.

“It was black music in a tuxedo,” Tarsia told me in 2018 at a 50th anniversary celebration. “There was the Motown Sound. The Memphis Sound. The Muscle Shoals Sound. And there was the Sigma Sound.”

Famously, David Bowie recorded Young Americans at Sigma in 1974. Bruce Springsteen took the bus from New Jersey to meet him, and teenage fans of the British rock star attained legendary status as the “Sigma Kids.”

On Wednesday, a group of Sigma Sound veterans from the studio’s glory days joined a younger generation of Philly music lovers and preservationists for a #SaveSigma brainstorming session, to mull the future of the gutted building that has been owned by real estate developers since 2015.

The meeting was called by Max Ochester, the mover-and-shaker owner of the Brewerytown Beats record store and label, an impassioned advocate for the preservation of Philly music.

Ochester wants to not only save the Sigma Sound building, but also turn it into a museum.

“Not a Sigma museum,” he said. “But a Philadelphia music history museum” — an institution sorely lacking in a city that has been home to Marian Anderson, Billie Holiday, Eugene Ormandy, Hall & Oates, Schoolly D, and the War on Drugs.

Speakers at the Sigma summit, held at the Spring Arts Building in Callowhill, included David Ivory, who engineered Erykah Badu’s 1997 album Baduizm at Sigma, as well as several by an up-and-coming Philly band called the Roots.

Ivory is a member of the Philadelphia Music Industry Task Force started by City Councilman David Oh in 2017, which is holding a public meeting at City Hall at 1 p.m. March 12. A subject that will come up: opening an official city Music Office.

Along with the Uptown Theater in North Philly, where James Brown and Aretha Franklin once performed, Sigma is the city’s single most important music landmark in need of safeguarding, Ivory said. “It’s Sigma and the Uptown, to be honest.”

In an Inquirer story in January about Brewerytown’s reissue of an album by the 1970s soul group the Thompsons, Ochester referred to Philadelphia as “the city that sleeps on itself,” often guilty of giving its own cultural history short shrift.

Ochester will be part of Saving Philly’s Soul: The Why Live on March 20, a discussion with radio host Dyana Williams and WHYY-FM (90.9) journalists Annette John-Hall and Shai Ben-Yaacov, with a free performance by Philly band York Street Hustle at WHYY’s 6th Street studio.

On Wednesday night, Ochester rued the reality that so many of Philadelphia’s vintage recording facilities are gone. Among them: 309 S. Broad Street, which housed the Cameo Parkway label, where Tarsia gained technical expertise working on records by Chubby Checker and the Orlons.

Gamble, Huff, and Bell bought that property in 1973, and located the Philadelphia International Records office there, as well as a studio operated by Sigma. A fire in 2010 damaged the building, though, and it was sold and razed in 2015.

“The only one that’s left is Sigma,” said Ochester.

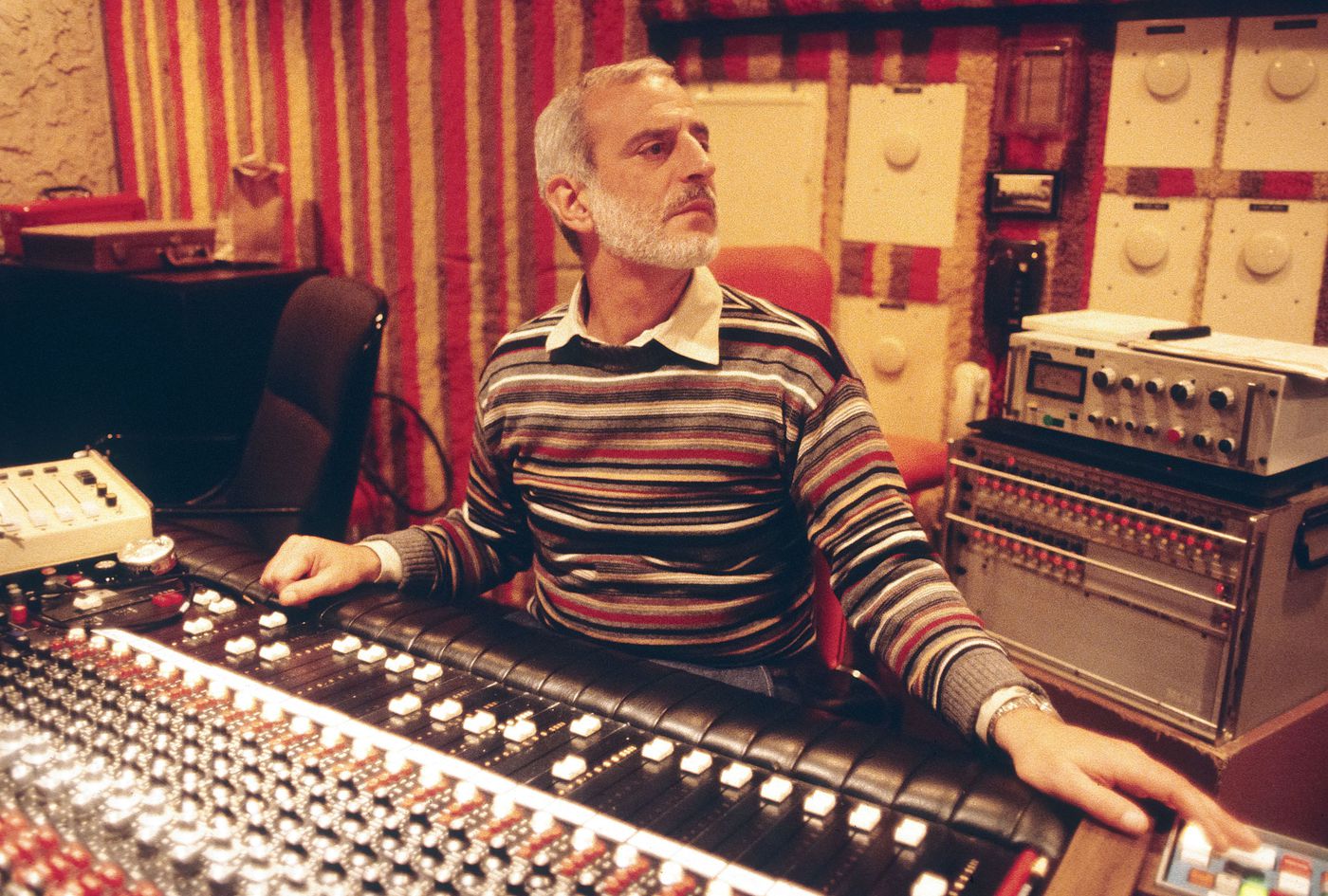

Sigma’s illustrious history was demonstrated in a slideshow by Arthur Stoppe, an engineer who worked there from the early ‘70s through the 1990s.

His pictures told the story.

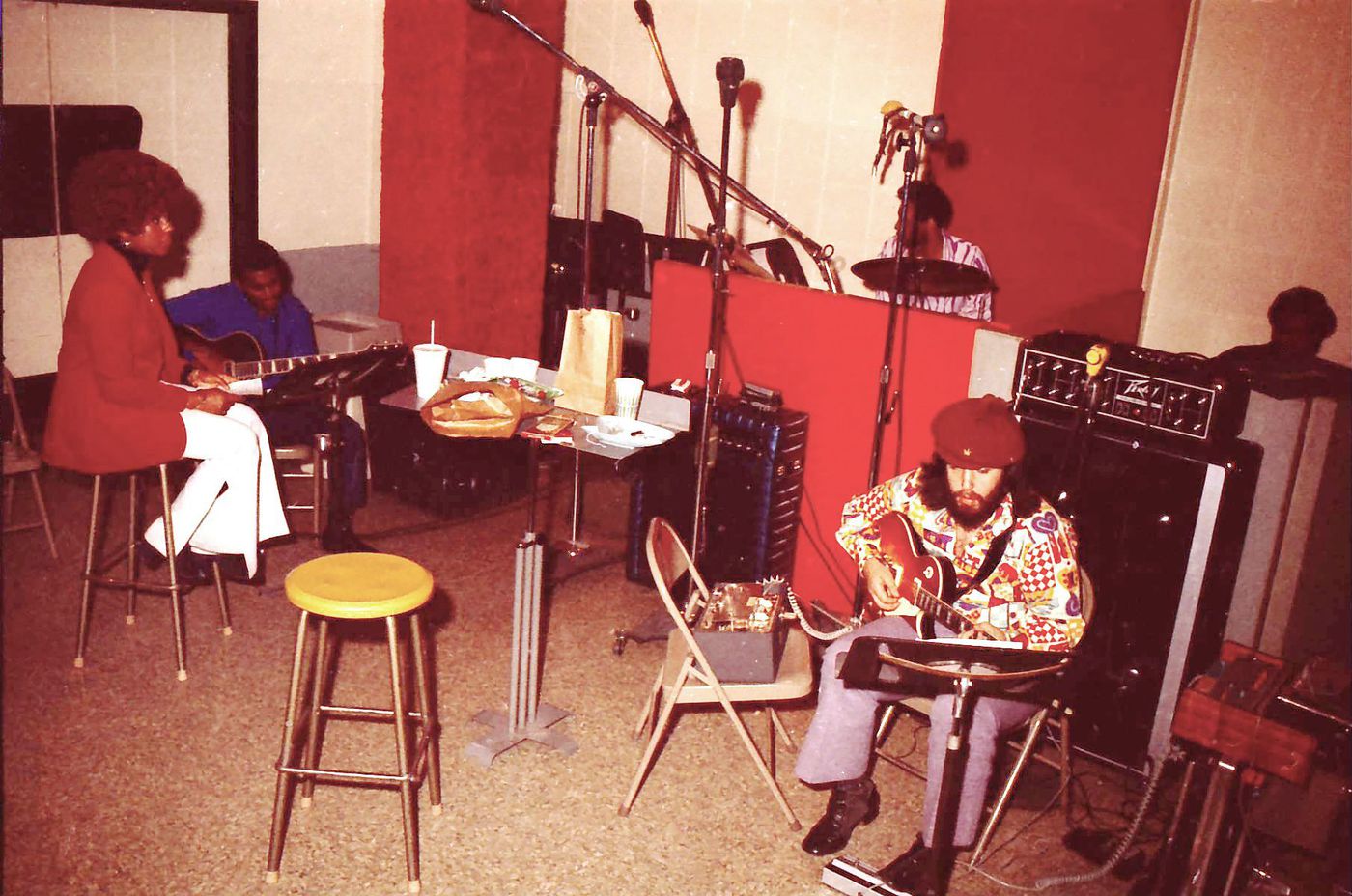

There’s Barbara Mason of “Yes, I’m Ready” fame in the studio with Ron Baker, Bobby Eli, and Earl Young, all members of Philly International backing band MFSB. Young was also a member of the Trammps, and his is the bass vocal heard on the 1976 hit “Disco Inferno.”

There’s Bowie at Sigma with then-girlfriend Ava Cherry. And hey, look, it’s Lou Rawls, and Teddy Pendergrass, and a young Michael Jackson. (The Jacksons recorded two albums in Philadelphia in 1976 and ’77.)

The Tarsia family sold the business in 2003, and in 2015 developers bought the building and gutted it before construction plans stalled. That same year, a blue historical marker went up, noting that Sigma “was known worldwide for its distinctive sound and recording innovations.”

On Wednesday night, Patrick Grossi of the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia schooled two dozen avidly interested attendees about applying to the city for a status that could preserve the facade. (The marker, awarded by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, doesn’t protect the building.)

James Gorecki, the real estate agent who sold it in 2015 to Chinatown-based investors for $1.55 million, took questions. He estimated that the Sigma building — actually two properties at 210 and 212 N. 12th — is likely worth significantly more than that now. When he asked the owners a year ago if they were interested in selling, he said, the answer was no.

Ideas were batted around the room — about fund-raising, about programming, about the need to turn a proposed museum into a destination with interactive attractions and a performance venue.

At the moment, there are no active demolition or building permits for the property, Grossi said. But if the building is destined for development as a consequence of Philadelphia’s real estate boom, someone suggested, maybe apartments or condos could be built on top of Sigma, with the studio’s original two stories remaining intact.

Challenges lie ahead, everyone agreed after the meeting ran past its planned two hours.

The building itself “is nothing special,” said Toby Seay, a music industry professor at Drexel University, where over 7,000 Sigma tapes are housed. “But when you walk by it, you think, ‘Wow, on this spot, this happened here.‘ There’s something magical about that…

“It’s not a cheap proposition. But it would be a shame if it were to go away, because every place else is already gone.”

Ivory left optimistic, hopeful that the energy could lead to a Philly version of the Stax and Sun Records museums in Memphis or the Motown museum in Detroit.

“Great things start small sometimes,” he said. “We need this. It’s about preserving our heritage as a music force, in the country and the world.”

For Sigma vets like Stoppe, #SaveSigma holds out hope that the studio where they helped make history might have a future as a place of experience and learning for music fans.

“I’ve been dreading it every time I walk down the street. Is the building still there?” he said. “Now, after tonight, we know there’s a chance that it just may stay there. It’s a good thing to hear.”