Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

Adapted from Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia, Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture by Grace Elizabeth Hale, in stores now from the University of North Carolina Press.

For alternative music fans, the college town of Athens, Georgia, means the B-52’s and R.E.M. Through the 1980s, the city was synonymous with a kind of against-the-grain music epitomized by those two bands’ very different styles. In 1987, Rolling Stone named R.E.M. “America’s best rock ’n’ roll band.” Drummer Bill Berry denied it. The best band in America, he said, was Pylon.

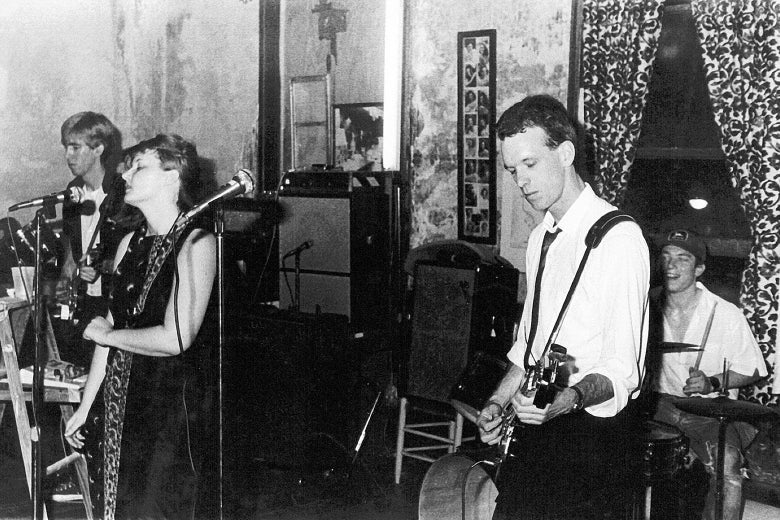

In its original incarnation, Pylon only lasted for five years. But no single band did more to define what it means to be an Athens band than Pylon. Formed as a performance art project by four art students who mostly did not know how to play their instruments, Pylon created a startling, original sound by combining formal experimentation with a danceable beat. Beyond their music, band members’ commitment to making art in their small, Southern college town helped transform what had been a tiny network of art students and their friends into one of America’s most important and enduring music scenes. This is the story of how, in that period when what would become alternative was new, Pylon broadened the very idea of what a band could be.

In Athens, Georgia, people got into bands the way people everywhere get into most things—through their friends.

As a high school student in suburban Atlanta, future Pylon bassist Michael Lachowski had taught himself photography by reading the Time/Life photography series and building a darkroom in his parents’ house. He met Randy Bewley, future guitarist, in the photography studio at the University of Georgia where the sculpture major from suburban Atlanta had a work-study job. Outside class, Lachowski made drawings, prints, Super 8 films, and sculptures, as well as photographs. Bewley made photographs and other two-dimensional work and later switched his major to painting. As Lachowski remembered, this kind of experimenting with genre just seemed normal at UGA: “We had an exuberant group of people; creativity was prized above all else; everybody was just putting out work. It led to us going out of the boundaries of our disciplines. A lot of us in the art school were trying out different media with a punk rock message, which is just go in there and do it. You don’t need training, or authority or legitimacy. Just figure it out.”

At the UGA library and at Barnett’s News downtown, Lachowski and Bewley followed the art and music news in publications like the Village Voice. After the B-52’s started playing New York City regularly in 1978, Bewley and Lachowski read about people they actually knew. Bewley wanted to form a band, too. Lachowski resisted. His problem with the idea was not that they were not musicians. The fact that they had no experience playing instruments was no different from the fact that they had no experience making prints or installation art before they went to art school. They could learn. Instead, Lachowski hesitated because making music seemed unoriginal: “I thought it had been done already.” But then the friends had an idea. As the band’s singer Vanessa Briscoe Hay remembered, “They’d been reading New York Rocker, and it seemed like it would be an easy thing to have a band and go to New York and get some press and come back. And that would be it.” Once they got the press, they would quit. Instead of a band, they decided, they would create a kind of performance art.

Bewley bought Lachowski a bass at a pawnshop and found a guitar for cheap at a flea market. Sometime that winter, the two friends started practicing regularly in Lachowski’s off-campus studio, a second-floor space on College Avenue right across from the university. Lachowski worked from a bass instruction book. Bewley played his guitar with an alternate tuning because he did not know the standard one. Plugged into little Pignose amps, they practiced by alternating positions, with one holding the groove and repeating a phrase while the other experimented.

In the future, these long jams would give birth to a remarkable independence between the bass and the guitar parts. At the time, they sounded like “endless riffs.” Curtis Crowe, their landlord, who lived upstairs, remembered hearing “a never-ending series of hooks—no bridges or chorus, just hooks” echoing and vibrating right up through the floor. One day Crowe reached his breaking point: “So I kinda went ahead and knocked on the door lookin’ real timid and said, ‘Hey, mind if I drag these drums in here for a little bit?’ ” The band’s future drummer “had every song memorized before I ever went down.”

When Bewley and Lachowski decided to find a singer, it made sense to them to ask art students whose work they liked. Bewley’s friend Vanessa Briscoe Hay—then Vanessa Ellison—had started out in arts education before switching her major to drawing and painting without telling her parents. After she graduated, she got a job at the local DuPont nylon factory, through word of mouth at the art school. Bewley was still in school, but Lachowski got a job there too after he graduated. Bewley told her about a performance art project he, Lachowski, and Crowe had created that involved making music. Bewley wanted Briscoe Hay to try out for the role of singer. She told him she wasn’t really a musician. Bewley insisted they were all amateurs. What mattered was they respected her as an artist.

The audition at Lachowski’s studio turned out to be oddly formal. On a music stand, her future bandmates had placed an orange vinyl notebook full of typed lyrics. They would play a song, and she would try to make the lyrics fit, sometimes cracking up in the attempt. “They couldn’t really hear what I was doing,” she remembered, but “they liked the fact that I put forth some honest effort and they liked the way I looked, and they liked me as a human being.”

When the band debuted on March 9, 1979, in the second-floor space downtown above Chapter Three Records, it was hard to imagine its members would soon be local stars. All the songs they played were originals, except the theme song from Batman. Briscoe Hay stood on a mirror with her back to the big windows that looked out on old campus and concentrated on the words. Bewley and Lachowski looked at their hands. Only Crowe seemed at ease. In Athens, everyone danced at parties, and yet the audience at that first Pylon show and a second at Crowe’s loft stood strangely still. As Crowe told a critic in 1981, “Nobody knew what to do, so they were real polite.” In a letter to a former professor, Lachowski added a list of comments he had heard after their first few gigs: “too art oriented,” “conceptual,” “they sound like a bunch of artists who got together and decided to have a band,” “Michael, your music sounds just like your art,” and “they’ll like what you’re doing in New York (as if to imply that they don’t really in Athens).”

At their third gig, though, at a house in the country, everything changed. As Briscoe Hay recalled, “The B-52’s showed up at that party, and they started dancing and running around like crazy and everybody else did too.” After the show, Briscoe Hay said, Fred Schneider and Kate Pierson “were very supportive.” They said, “You’ve got to play New York.”

To get that date, Pylon had to make a demo. Someone bought some Kmart cassette tapes, and the four art students recorded themselves playing a few songs at Lachowski’s studio. Then Schneider gave a tape to Jim Fouratt at Hurrah, a punk dance club where the B-52’s had been playing lately. The timing was perfect. “Rock Lobster” was a New York hit, and the B-52’s reached the peak of their underground fame in the weeks before the release of their first album that July. Fouratt actually called the members of Pylon in Athens, read through a list of coming bands, and asked them who they wanted to open for. Bewley and Lachowski picked Gang of Four.

In New York, a huge crowd filled with other musicians turned out at Hurrah to see Gang of Four. Briscoe Hay borrowed a whistle from the doorman and blew it during the song “Danger.” People in the front shook Bewley’s hand after the set and badgered him with questions about how he came up with his strange tunings and original chords. After they got back home, the September 1979 issue of Interview arrived with Glenn O’Brien’s review that gave as much space to Pylon as to the Gang of Four:

Pylon, the first Athens band to hit the town since the B-52s. A tough act to follow—but Pylon is also a credit to their community. There’s not much resemblance to the Bs. Although the guitarist has real classy taste in licks that is sometimes reminiscent of RICKY WILSON’S. Pylon has a charming chanteuse up-front—sort of Georgia Georgie Girl who manages to carry off several difficult postures, including kooky, endearing, sincere and wry. And not all the songs sound the same. These kids listen to dub for breakfast. Recommended.

Interview was not New York Rocker, but O’Brien’s coverage was better than the band members’ dreams, even if they had to look up the meaning of the word dub. Their project was a success, but they did not want to quit. They were having too much fun.

In making their performance art rock, the four members of Pylon drew on what they had learned in art school about the ways that tensions between materials, mediums, and expectations could animate art. Middle-class kids holding down working-class jobs, they turned the factory into a style. Posters featuring orange safety cones and music full of machinelike repetition punctured by whistles and screams contradicted audience assumptions that small Southern towns produced only county and folk sounds and handmade things.

Their name referred to “the kind in the road, not the architectural one or the ones that hold up electricity,” as Lachowski wrote a former professor. “We chose Pylon because it is severe, industrial, monolithic, functional. We subscribe to a modern techno-industrial aesthetic. Our message is ‘Go for it!, but be careful.’ ” Working the contrast between flat, machinelike minimalism and ragged, Southern-accented amateurism, their songs used a four-on-the-floor disco beat to mash together punk’s emotional excess and industrial repetition and detachment. The bass throbbed and the drums boomed as guitar licks cut across the rhythm section without being leads. The vocals varied from deadpan recitations of short phrases to howls, and Briscoe Hay rarely flirted with the audience. Instead, she belted out vocals while bouncing up and down and shaking her head like a dancer in a Charlie Brown television special. Sometimes, she blew a shrill whistle midsong, like a referee or a cop.

Live, Pylon’s act could be shocking or jolting or heavy. It could also be deep. In fusing pop and rock forms with an avant-garde sensibility, the band members asked what art could mean in the midst of industrial decline, production-line mass culture, and rising political conservatism. And they tentatively offered an answer. “Be careful, be cautious, be prepared,” the lyrics of their song “Danger” warned. But be creative, too. “Everything is cool.” “Turn up the volume.” “Turn off the TV.” “Now, rock and roll, now.” “Read a book, don’t be afraid.” “Function precedes form. Things happen.” Pylon pushed people to think as well as dance, to put their minds and bodies back together. Playing live, the four art students could pound their awkwardness and their amateurism and their artistic vision into something transcendent. If people in Athens revived on a local scale that old dream that music could make a new world, it was because they were living it.

Pylon nurtured the creativity the B-52’s had helped spark in Athens before they left for New York. Pylon’s performances, shows by other bands, and art installations by Lachowski and others transformed the open space behind the Victorian house at 265 Barber Street where Lachowski lived into Pylon Park, one of the emerging scene’s important gathering places. The band also played the club Curtis Crowe started, the 40 Watt Club. In the summer of 1980, Briscoe Hay had to quit her job at DuPont when the B-52’s invited Pylon to open for them in New York’s Central Park. By the end of the year, band members found they could live two or three months in Athens on their New York City guarantees. Pylon became their job.

Over the next three years, Pylon toured the Midwest and Canada with the Gang of Four and played a string of dates in England. In January 1982, they sold out the large Memorial Hall ballroom on the University of Georgia campus. In April, when the 40 Watt moved from Clayton Street to a bigger venue on Broad Street, they headlined the back-to-back closing and then opening shows and packed both rooms. In Athens, Pylon ruled the scene that the band’s members had done so much to create.

If Pylon seemed wildly successful from an underground perspective, outside Athens, New York, and a few other cities, audiences often did not seem to know what to make of the group. Band members made enough money to live cheaply in Athens, but they weren’t exactly comfortable. To reach the next level, they hired a professional booking agent. He landed them a gig most bands would have been giddy to get: the opening slot for U2’s U.S. tour in support of their recently released album War. When they took the stage, crowds impatient to see the Irish band ignored them. As Briscoe Hay recalled, “People were heckling … ‘Where’s U2?’ and ‘Get off the stage.’ ” What everyone said was great felt instead like failure. It certainly was not fun. Maybe they did not really want this kind of success. Maybe their performance art–turned-band was exactly what they said it was, “temporary rock.”

At the beginning of 1983, Briscoe Hay told a local Athens paper, “I think if it ever became miserable, we would just disband,” and in retrospect she was hinting at what was to come. Band members decided around this time to break up at the end of the year, after they fulfilled their bookings, but they kept their decision secret. In Athens, most people found out when posters went up for “Pylon’s Last Show” with opening act Love Tractor.

A recording of that farewell show released in 2016 finally gave those of us who missed it a chance to listen in on this essential moment in Athens history. From the opening note of the first song, “Working Is No Problem,” Pylon played 22 songs with hair-on-fire intensity that did not let up until the five-song encore finished. Over the course of approximately an hour and a quarter of music, the crowd roared out its encouragement. Sometimes the fans sang along to lyrics like “Everything is cool” and even occasionally to guitar hooks, like the woo-woo of “M-Train.” At other times, they just yelled. No one wanted the evening to stop.

Interviewed afterward about the breakup, band members reflected on why they had started making music “as another form of artistic expression.” “We accomplished what we set out to do,” Lachowski said. “It’s not that we are miserable, it’s just that we’ve seen all we’re going to see and don’t want to put any more time into it.” “What was frustrating was not trying to live like other bands, but trying to convince everybody that we didn’t want to do it that way,” he explained. “We were the only ones that understood why we were not out there with the other bands trying to make it big.”

A critics’ darling, repeatedly named the best band in Athens, Pylon carried its art piece so far that it broke up on the cusp of stardom. “We’ll become a cult band now,” Bewley predicted on the eve of Pylon’s last show. “This is a type of suicide that’ll make us more popular in the long run.” And he was right.