The city’s soul is wounded. Crime is up, children are being killed and the simple lights of summer are shadowed by orders of distancing. Some rules are too much to remember, but this should never be forgotten:

The summer of 2020 is the fiftieth anniversary of the hit Chicago pop-soul ballad, “O-o-h Child.”

It is a song of healing.

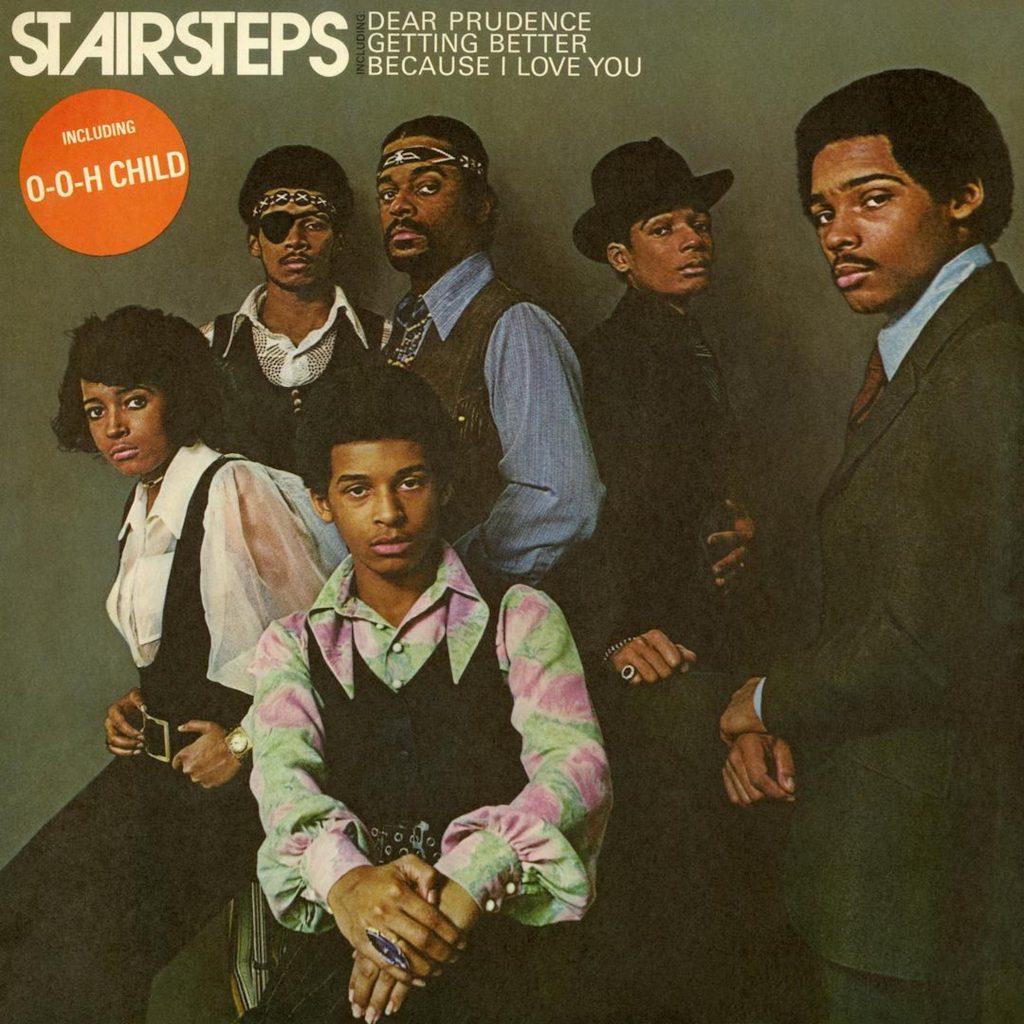

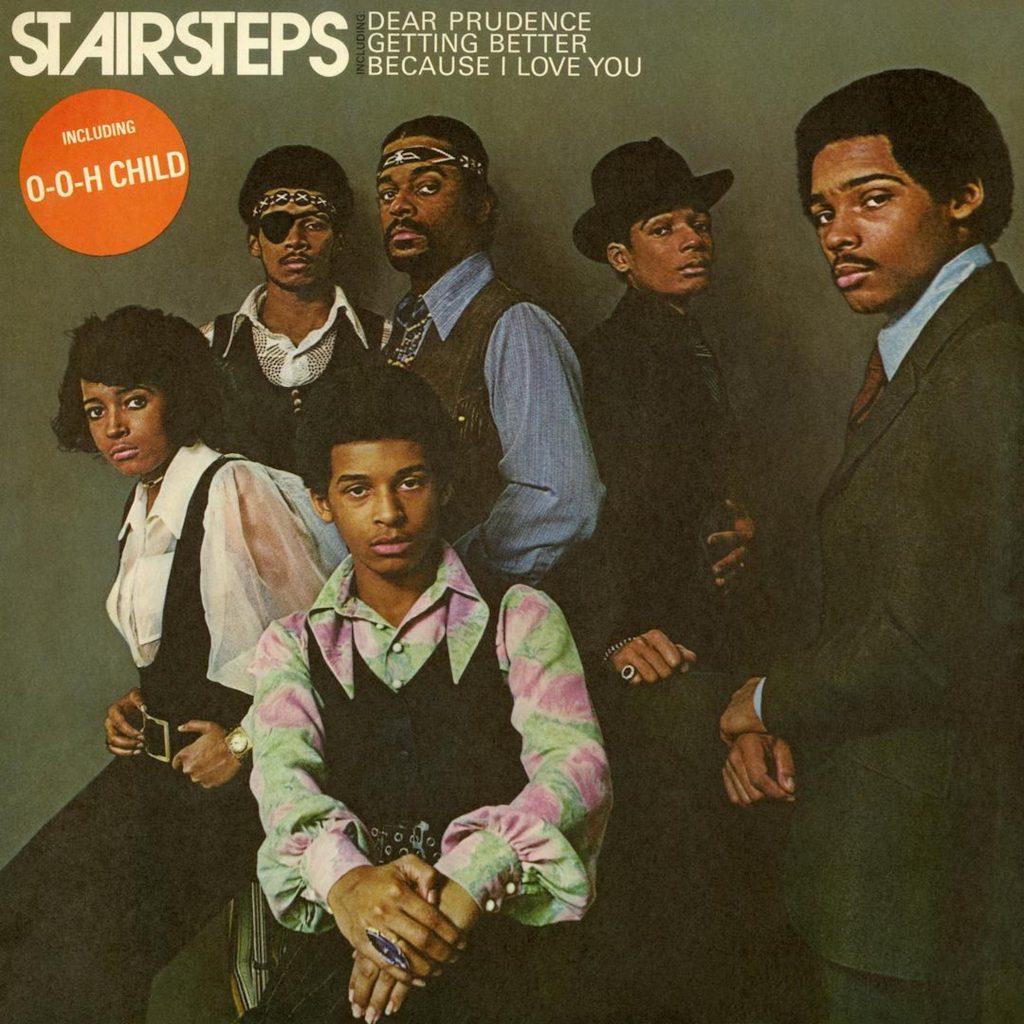

“O-o-h Child” was recorded by The Five Stairsteps, a South Side precursor to The Jackson 5. The group consisted of five of the six children of Betty and Clarence Burke, Sr. Clarence, Sr. was a detective for the Chicago Police Department. He also played bass and later managed The Five Stairsteps. The young-blood harmonies are so soothing and so hopeful on “O-o-h Child.”

“….Some day, yeah

We’ll walk in the rays of a beautiful sun

Some day

When the world is much brighter……”

I’ve heard the song a thousand times and it still makes me cry. The cresting horns hit all the hopeful notes of Chicago soul music and the chorus honors a universal possibility. Rolling Stone listed “O-o-h Child” at number 402 on its 500 greatest songs of all time.

The “O-o-h Child” backstory is also one of the greatest of all time. The soul ballad was written by Stan Vincent (Stanley Grochowski), a New Yorker who began his show business career as a kid actor on the Chicago-based mid-1950s Saturday morning TV series, “Watch Mr. Wizard.” He later wrote hits for Connie Francis and managed a couple of New York doo-wop groups.

Vincent fell into The Five Stairsteps orbit after pop artist Lou Christie had a smash 1969 hit with Vincent’s “I’m Gonna Make You Mine.” Christie recorded for Buddha Records, then a pop-bubble gum imprint. In the summer of 1970, Vincent composed, arranged and produced “O-o-h Child” for The Five Stairsteps. The Vincent connection is how the iconic soft soul hit wound up on Buddha. The song has since been covered by Nina Simone, the Wondermints and Dusty Springfield. It has become a staple of the live sets of the popular Chicago band Expo 76, fronted by Dag Juhlin.

L-R: James, Alohe, Dennis, Clarence Jr. (center) and Keni (bottom) / Photo courtesy of Keni Burke

It took a few weeks for me to track down the Burke family. My friend Joyce Moore (married to Sam Moore of Sam & Dave) unlocked the key. She is friends with bassist Keni Burke through his post-Five Stairsteps affiliation with the late keyboardist Billy Preston.

Keni, sixty-six, is doing fine in Atlanta, Georgia. He was a member of Bill Withers’ band and played bass and co-produced Withers’ 1977 album “Menagerie,” which included the hit “Lovely Day.” Burke’s parents are in Marietta, Georgia and they both enjoyed their ninety-first birthdays in July. “We just celebrated Father’s Day,” Burke says. “Both of them were up dancing. They’re mentally sharp, just amazing.”

Clarence Burke, Jr. died in May 2013 at his home in Marietta. He sang the Stairsteps’ lead in a sultry Smokey Robinson style. The oldest brother had turned sixty-four the day before his death. The cause of his death was not disclosed. Cubie Burke joined the group when he was three years old when they morphed into The Five Stairsteps & Cubie. Cubie became more popular as a dancer than a singer. He performed with Dance Theater of Harlem. Cubie died in May 2015 in Smyrna, Georgia. He was forty-nine.

Besides Keni, surviving siblings are Alohe, seventy-two, (contralto) who now goes by the name Rami; James, sixty-nine (first tenor); and Dennis, sixty-eight (baritone). The entire family is in the Atlanta area and Keni is the only one still active in the music business.

Like the great soul artists Curtis Mayfield and Major Lance (whose daughter Keisha Lance Bottoms is the mayor of Atlanta), the Burkes migrated from Chicago to Atlanta in 1974. They did take up residence in New York City in the early 1970s. Keni lived in Los Angeles from 1974 to 1985.

Keni keeps a photograph of Chicago soul great Curtis Mayfield on his dresser. Mayfield signed The Five Stairsteps to their first deal. “And it was Curtis who introduced us to Atlanta as a place we might want to consider living,” Keni says. “Atlanta was a beautiful new town on the rise. Growing up in the 1950s and sixties, we never felt any of the socio-political things going on in Chicago. We were so young. Moving to Atlanta we were a very close-knit family. We knew about civil rights of course, but it was more lessons than actually being on into it.”

The Burke family grew up in a four-bedroom brick house on East 99th Street and King Drive. The kids sat together on the living room couch and bounced their heads to the rhythm of soul music. The children were lined up on the couch in such a way where their mother said they looked like stairsteps. The Burkes sang along to early Miracles and Marvin Gaye songs. “My dad would give us some pointers, but it was more Clarence, Jr., who kept us moving cohesively,” Keni explains. “He taught the choreography. And he never danced in his life!” Clarence, Jr. and Alohe attended Harlan High School. “I was in the seventh grade when our careers blew up,” Keni says. “I didn’t make it to high school at all.”

Clarence Burke, Sr. became a Chicago policeman in the early 1950s. His late brother Marcellus was also a Chicago cop. Burke, Sr. always wore a black trench coat and a black Dobbs fedora. He retired in 1966 after The Five Stairsteps signed with Mayfield. “I remember seeing my dad on the news when I was little,” Keni says. “He was shot in the lower back. He was laid out on a stretcher. Another time my mom and dad were driving together and he saw a taxi driver being held up in front of them. My dad went into a shoot-out with the robber while my mom was in the car. He told her to hit the floor.

“My dad was no joke.”

Burke, Sr. reminisces about his days as a Chicago cop. “There were very few Black officers at the time,” he says. One other Black Chicago cop who successfully transitioned into music was the late Don Cornelius, the founder of “Soul Train.” Cornelius also left the force in 1966. Burke, Sr. and Cornelius were ex-Marines.

Clarence Burke and his partner Luceke “Zeke” Mays climbed up the CPD ladder after solving the brutal 1959 murder of Thelma Campbell, the sister of Twentieth Ward alderman Kenneth Campbell. During the 1960s Burke was assigned security to visiting dignitaries like Frank Sinatra and President Lyndon Johnson.

Burke was raised on the South Side. He was a CTA streetcar driver before becoming a cop. In the early 1950s while on his CTA job he helped firemen tend to victims at a State Street fire. “I wanted to be a servant to the city and its people,” he says.

Burke used his connections to help get his kids to perform on Chicago radio shows. Then in 1965, The Five Stairsteps won the three-day talent show at the original Regal Theater. They sang Smokey Robinson’s “Ooh Baby Baby.” Keni recalls, “Even the Jackson family was on the show. We were friends with them. Their father Joe Jackson confided in our father. But we were first. And we paved the way.” The Five Stairsteps were known as “The First Family of Soul” before The Jackson 5 was known as “The First Family of Soul.”

“My children have been my life,” Burke says.

I tell him he did a good job. “Well, they did a good job of keeping the old cop alive,” he answers.

Before moving to their house on East 99th, the Burke family lived in a townhouse on East 87th and South Park. Fred Cash and Sam Gooden of the Impressions lived about five doors down. The elder Burke kept telling Cash about his family group. Cash finally heard them sing in their 99th Street living room. They sang the ballad “World of Fantasy,” written by Burke, Jr. and Gregory Fowler. “Fred listened to about twelve bars,” Keni says. “He stopped us and said, ‘Can I use your phone?’ He called Curtis (Mayfield). We were ushered off to Marina City to meet Curtis.”

Mayfield had an apartment in Marina City. In 1966 he signed The Five Stairsteps to his short-lived Windy C label. Mayfield also saw his younger self in the group, writing ballads like “Stay Close To Me” and in 1968 giving them “I’m the One Who Loves You,” which he wrote for Jerry Butler in 1962.

The Five Stairsteps’ television appearances ranged from a poised appearance on “Soul Train” to the elder Burke being a 1967 detective/musician on the “To Tell The Truth” quiz show. The Five Stairsteps gave the straight-laced panelists a live performance of their Mayfield-Burke, Jr. and Fowler-composed jazz-tinged single, “Danger! She’s a Stranger.”

Burke shepherded his children around the country to sing their uplifting songs. A couple of months before the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, the Burke family had occupied the same room that would be given to Dr. King.

Two years later, “O-o-h Child” was a hit across America.

“The time was right for that song,” Burke says. “‘Things are going to get easier. Right now.’ It made sense. The tunes that make it are the tunes that have a message. When a prayer can be answered because of a message, you have a hit.”

Keni says, “My dad was on the front line. He dealt with the promoters. Without him, especially with us being children, there would have been no way we would have made it. And being a policeman our parents were aware when we were growing up. That’s when the Blackstone Rangers and the gangs were starting to emerge. When my dad started seeing the gang initiations he was like, ‘Okay, maybe I will let my children go into the music business.’ That was a way to get away from all that.”

The Five Stairsteps ascended to new heights after “O-o-h Child.”

“O-o-h Child’,” Keni says with a laugh, and he pauses. “Wow. We were performing at the Apollo. We were introduced to Stan Vincent. Here we were this R&B group who had worked with Curtis Mayfield. And here’s this white kid coming up the stairs of the Apollo. We’re like, ‘Cool.’ We were always rockers anyway. Jimi Hendrix, The Beatles. We knew Stan wrote the Lou Christie hit. It was a challenge doing Stan’s songs because they were different for us. At the time, we never knew ‘O-o-h Child’ would be what it became.”

Buddah first released The Five Stairsteps’ edgy, funky cover of the Beatles’ “Dear Prudence” as the A-side of the 45. “O-o-h Child” was the B-side. “Dear Prudence” flopped. A Philadelphia DJ flipped the 45 and “O-o-h Child” took off. “It was all a fluke,” Keni says.

“O-o-h Child” was recorded at Allegro Studios in New York City, where Dion recorded his 1968 civil rights hit “Abraham, Martin and John.” Vincent assembled a crack band with Bernard Purdie (Aretha Franklin, James Brown) on drums. Hugh McCracken on lead guitar (that’s his guitar fills on Van Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl”), Richard Tee (Aretha, Donny Hathaway) on piano, Clarence Burke, Jr. on guitar and Keni on bass.

As the Burke family got to know Vincent they learned how he also grew up as a youngster in Chicago show business. Vincent went on to become business manager for Jack Douglas when he produced the 1980 John Lennon-Yoko Ono album “Double Fantasy” and Vincent brought his old “O-o-h Child” guitarist McCracken into the Lennon-Ono sessions.

How does Keni explain the everlasting spirit of “O-o-h Child”?

“The lyrics are on point,” he says. “They speak to everyday life no matter where you are in your own life. People are going through struggles. The Vietnam War was ending when it came out. There was social change. But the record also has a feel to it. Something about it brightens your day. And when my dear sister sings the first verse, her voice is so soothing it puts everybody in this mood. It’s like a warm blanket to the soul.”

Between 1973 and the early 1980s Keni played with Billy Preston (a.k.a. “The Fifth Beatle”). After “O-o-h Child” the group was signed to George Harrison’s Dark Horse label. “Billy had a ranch in Topanga Canyon (California),” Keni says. “A lot of folks would come over. One day George came by. He was looking to sign some acts. I had recorded four demos at Curtom (Mayfield’s studio in Chicago). I played them for George and he liked it. I had moved away from the family doing my own thing. Billy said I should bring the family back in on it so I did.”

The result was 1976’s “2nd Resurrection” by The Stairsteps. They dropped the “Five” and moved into a heavier synth-driven funk sound. In 2001 Mojo magazine called “2nd Resurrection” one of the one-hundred best soul albums of all time. “We had a top ten R&B hit (the uptempo horn driven) ‘From Us to You’ that I wrote, but the album didn’t do what we felt it should have. So the family went on their way so I stayed on with George.”

Keni met Bill Withers in 1977 and they remained collaborators and friends until Withers died earlier this year. Withers first asked Keni to co-produce three Withers tunes for the 1977 “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” soundtrack. “He was my most favorite human being in the record business, bar none,” Keni says. “Down to earth. Never changed. Bill was fifteen years my senior. When I was doing session work in Los Angeles most people didn’t know I was a Stairstep. But he knew about ‘O-o-h Child.’ He was a man of principle.”

Through his second marriage, Keni became the son-in-law of the late jazz trumpeter Gil Askey, a long-time musical director for Diana Ross. Keni is currently producing the power ballad “Time on My Hands” that he wrote for soul legend Little Anthony. Narada Michael Walden (Journey, Weather Report) guests on the drums. “Our dad took us to see Little Anthony and the Imperials in Chicago,” he says. “That was our first concert.”

The Imperials’ songs were softer and smoother than the beat of a Chicago cop. The retired detective/music manager says, “Oh my, I worked Wabash Avenue, one of the toughest districts on the South Side. I was wounded twice in the line of duty. My children sang all the time and it was just a thrill to come home to my children. More than a pleasure.

“More than God’s will.”

Dave Hoekstra is a Chicago author, radio host and documentarian. His latest book “The Camper Book (A Celebration of a Moveable American Dream) is available on Chicago Review Press. He co-produced the documentary “The Staple Singers and the Civil Rights Movement,” nominated for a 2001 Chicago/Midwest Emmy Award. Dave was a 2013 recipient of the Studs Terkel Community Media Award. His work can be found at davehoekstra.com.