Filed under:

Before retiring from the Chicago Police Department in the mid–1960s to manage the group known for its hit ‘O-o-h Child,’ he was one of the city’s few Black detectives.

On a raucous night at the old Regal Theater in the mid-1960s, Detective Clarence Burke Sr. watched and waited.

Besides being a Chicago cop, he was the father and manager of the members of the singing group The Five Stairsteps — the name their mother Betty bestowed on the couple’s five kids for the descending order of their heights.

They’d sung and played their hearts out in the talent competition at the theater at 47th Street and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, and the winner was about to be named. The place was throbbing with music, adrenaline and anticipation.

“It was jumping,” said Keni Burke, one of the group’s members. “It was 30 or 40 acts over a three-day period.”

But it was no contest. The crowd roared loudest for the Burke kids, so they were the winners.

Keni Burke said another group of singing siblings, from Gary, went home empty-handed that night: “We beat the Jackson Five.”

Mr. Burke once told a newspaper interviewer he and his wife “decided the experience would be good for them even if they lost, as long as they were ready to lose. Well, they won, and some of the top people in the Chicago music world began to take an interest in them.”

Mr. Burke, who died last month at 90, turned to a neighbor, Fred Cash of The Impressions, telling him, “You gotta hear my children.”

“We sang about eight bars,” Keni Burke said, “and [Cash] asked for the phone, and he called [Impressions band member] Curtis Mayfield and said, ‘I think it’s something you want to hear.’ ”

So the Burkes — Clarence Jr., Keni, James, Dennis and sister Alohe, who later changed her name to Rami — went to meet Mayfield, a soul music legend.

“We were 12, 13, 14, 15, 16,” Keni Burke said. “Can you imagine being ushered in on to see Curtis Mayfield, and you’re in Marina Tower, which you’ve only seen from a distance?”

Within a month, Mayfield had them booked at Chicago’s Universal recording studio, known for its early use of echo and multitracking.

“There was a full orchestra,” Keni Burke said.

The children wondered who it was for.

In his unmistakable falsetto, Mayfield told them: “That’s for you, babies.”

The Five Stairsteps went on to music immortality with the 1970 Stan Vincent song “O-o-h Child,” three transcendent minutes of soul and hope that’s now inspired listeners for half a century. On Aug. 18, its words were heard as Joe and Jill Biden hugged after her speech at the Democratic National Convention:

Ooh child

Things are gonna get easier

Ooh child

Things’ll get brighter. . .

Some day, yeah

We’ll walk in the rays of a beautiful sun

Some day

When the world is much brighter . . .

The song has been featured in movies including “Boyz n the Hood,” “Crooklyn,” “Guardians of the Galaxy” and “Shark Tale.” It’s been used on multiple TV shows and a “Grand Theft Auto” video game. It’s the chorus on Tupac Shakur’s “Keep Ya Head Up.” And Rolling Stone put it at No. 402 on its list of 500 greatest songs.

As The Five Stairsteps moved up the charts, the band kept slogging away at record hops, clubs and small shows. The group — later joined for a time by baby brother Cubie — appeared on bills with The Impressions, the Four Tops, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Otis Redding, Sly and the Family Stone, the Temptations and Jackie Wilson.

Through all of that, the proud band dad, who retired from the Chicago Police Department in the mid–1960s to manage The Five Stairsteps, chauffeured his kids around the country in first a red Chevrolet Impala station wagon and later an eight-door Checker Aerobus. He also played some bass.

And always he looked out for them.

Once, after a show in Pittsburgh, “My brothers and sister come off the stage, and they all had some kind of substance on their jackets,” said Keni Burke, who didn’t play that night because he was sick. Clarence Burke Jr. “said, ‘Dad, there was this guy in the audience, and he was spitting on us.’

“My dad said, ‘Point him out.’ The next thing you know, the guy was flying across the room with a backhand left. Then, he got him again with a righthand slap. Before he could get a third one, the guy took off running.”

Keni Burke wondered why his 265-pound dad — who once hit a would-be assailant so hard that he fell into a mailbox, knocking it out of the ground — used a slap instead of a punch.

His father told him, “Because, son, I wanted him to feel it. I didn’t want to knock him out.”

“He was always thinking,” his son said.

In 1967, Mr. Burke appeared on the TV show “To Tell the Truth,” and he and two imposters fooled some of the panelists, who couldn’t figure out which one of the trio was the father of the singing family.

Mr. Burke’s death, first reported by writer Dave Hoekstra, came at a Marietta, Georgia, hospital after surgery, his son said. The patriarch and much of the Burke family had moved to the Atlanta area in the 1970s.

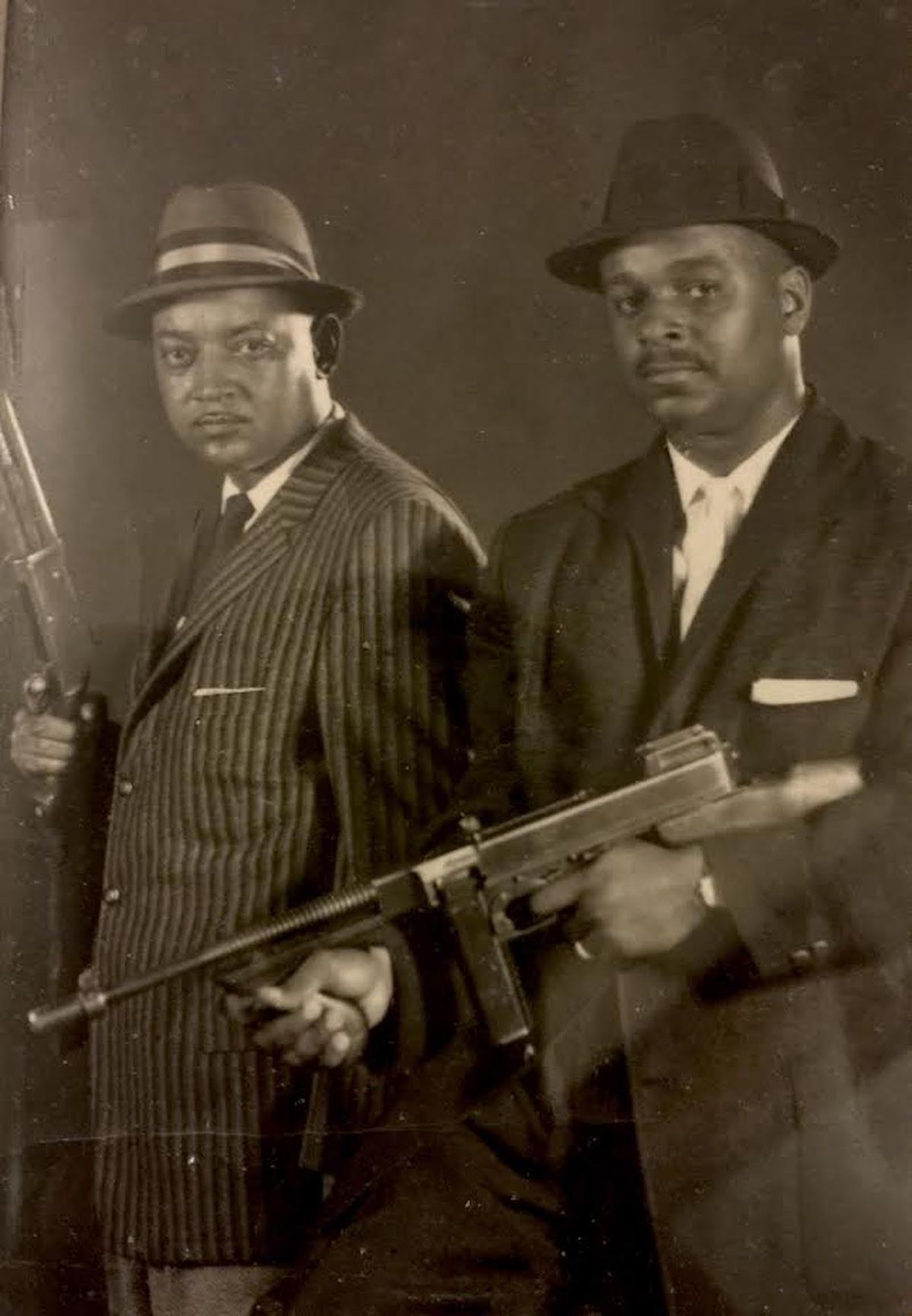

Mr. Burke, who’d been one of Chicago’s few Black police detectives, often made 1950s news headlines with partner Luceke “Zeke” Mays for solving murders and other cases, including the case of the Chatham cat burglar, who was said to have hit 30 homes by removing his shoes so he could soundlessly take valuables. Mr. Burke also once found a stolen $4,500 that had been wrapped in foil in the freezer of a man suspected in the holdup of an armored-car guard.

Another time, in 1960, Keni Burke said, “He got shot in a shootout. He took a bullet to the back. I can remember, on the news, my dad being put on the ambulance, on a stretcher.”

It wasn’t his only shootout, his son said. Once, while out driving, “My dad noticed a holdup going on in the taxi in front of him. My dad told my mom to hit the ground.

“He was the real, sho’nuff police,” the son said.

After Mr. Burke and his partner investigated the 1959 bludgeoning death of undertaker Thelma Campbell, sister of 20th Ward Ald. Kenneth Campbell, their work led the chief of detectives to promote both to permanent jobs in the detective bureau.

Despite the mayhem he saw, “It never came home with him,” his son said. “He was the kindest, sweetest guy. We’d all climb up on the bed with him, all of us, just jumping on him and playing.”

He also worked security for Frank Sinatra and President Lyndon Johnson and Lady Bird Johnson.

“Lady Bird had a corsage,” Keni said, “and she gave it to my father to give my mother.”

Mr. Burke’s parents were Florence and James Marcellus Burke Sr., who worked as a Pullman porter, and later as maitre d’ at the Palmer House.

Young Clarence went to Betsy Ross grade school and Tilden Technical High School. He worked as a CTA motorman and saw firefighters and police officers responding to an emergency nearby.

“That’s when he decided what he wanted to do,” his son said.

He married Betty, a grade school classmate, and they raised their kids in the Dearborn Homes on 29th Street and later a house in the 700 block of East 91st Place.

“In our home, music was so rich,” Keni Burke said, “we listened to all the jazz greats: Sarah Vaughan, Ray Charles, but even [opera singer] Mario Lanza. My uncle married a woman from Puerto Rico, so we listened to Tito Rodriguez, Tito Puente.”

Mr. Burke once told an interviewer: “Mom and I stayed close to the kids, and, when they were growing up, we dug the kind of music they dug. We didn’t do any pushing, but they naturally gravitated toward music, so we encouraged them. Most times, our apartment in Chicago sounded like a rehearsal hall.”

Mr. Burke is survived by his first wife Betty and their children Keni, Rami, James and Dennis, his second wife Alberteen, from whom he was separated, their son Martin, 13 grandchildren and many great-grandchildren and great-great grandchildren. His children Clarence Jr., Cubie, Terrill and Leonard died before him.

Keni Burke, a singer-songwriter and multi-instrumental musician, has worked with George Harrison, Billy Preston and Bill Withers. His music has been sampled by LL Cool J, Mary J. Blige and 50 Cent. And he performed last year with 50 Cent and Snoop Dog at Madison Square Garden.

But he said the voice he likes to hear most is his father’s.

“Every recording or message that went to my voicemail, I never deleted any,” he said. “I hear, ‘Son, I’m sorry I missed you. When am I going to see you?’ ”