In “Let Love Rule,” his new memoir, Lenny Kravitz recounts the first 25 years of his life, ending with the release of his debut album in 1989. The story he tells isn’t about stardom (that will come next, he says), but about the influences that inspired his distinctive musical hybrid of soul and classic rock.

Kravitz began his recording career at a time when hip-hop and dance-pop were ascendant. For years, as rap and electronic music became more prominent, he resolutely stood up for rock ’n’ roll, and watched as hippie ideals of peace and love drew snickers, and then began to seem less silly. He’s sold more than 40 million records worldwide, and despite playing throwback music, has released four Top 40 hits, including the gorgeous Philly soul tribute “It Ain’t Over ’til It’s Over” and the funk-rock stomper “Fly Away.” From 1999 to 2002, he won four consecutive Grammys for male rock vocal performance.

“He’s the epitome of cool,” said the actor Jason Momoa, the star of “Aquaman” and “Game of Thrones.” Momoa has been in a relationship with Kravitz’s ex-wife, Lisa Bonet, since 2005, and the Kravitzes, Bonets and Momoas have become an extended, blended brood. “It’s sad some families can’t get along,” Momoa said. “He’s super-chill, and he’s filled with love. When I’m with him, I feel special.”

The story of Kravitz’s early life is filled with revelations. The first comes when he sees the Jackson 5 at Madison Square Garden. Then he goes to a James Brown concert, which he calls “my second life-changing moment.” When he’s 11, his mother is cast as one of the lead roles in “The Jeffersons,” the groundbreaking interracial sitcom, and the family moves to Santa Monica, Calif., where in quick succession he discovers Led Zeppelin (“Maybe the moment”), skateboards and marijuana. Epiphanies continue to occur: Kiss. Steely Dan. Choral music. The opera “Tosca.” And, on the same plane of importance as Led Zeppelin, Prince. “When I saw Prince, I saw myself,” he writes.

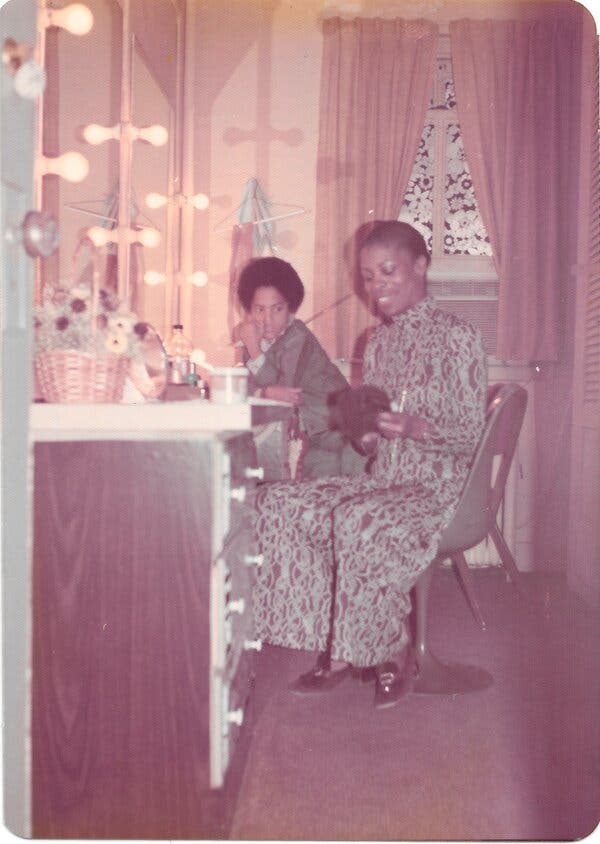

Parallel to this series of musical milestones, he develops a close relationship with his mother, the actress Roxie Roker, “a beguiling Caribbean-American woman” who seems to have known every Black artist and intellectual of the 1970s, and a difficult relationship with his disapproving father, the TV news producer Sy Kravitz, “a self-assured Jewish man” whose parents refuse to attend his wedding to Roxie.

“I am deeply two-sided,” Kravitz writes. “Black and white. Jewish and Christian. Manhattanite and Brooklynite.”

He meets Bonet, a star of “The Cosby Show,” backstage at a New Edition concert. Like Kravitz, she is the child of a mixed-race couple. “It was like she was the female version of me,” he writes. She pays for him to record the demos that eventually lead to a recording contract, after he spent years declining deals that would’ve required him to change his style of music. And in late 1988, they have a daughter, Zoë Kravitz, now an actress whose starring roles include a show about musical fandom, “High Fidelity.”

Kravitz, 56, had been in his Bahamas home for six months when we talked in late August. He’s a rambler, so being in one place for that long “is a new experience,” he said and laughed. He answered a Zoom call in jeans and a Talking Heads “Remain in Light” T-shirt and spoke convivially about his memoir, whether he can remain committed to nonviolence and the “horrific” thing his father once said to him. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

While you were writing your memoir, did you notice any patterns or themes in your life?

A lot of acceptance and forgiveness. Thinking deeply about things I hadn’t thought about was very healing. Especially in the case of my father.

When you were 16, he threw you out of the house, and you were itinerant for a few years. Did you remain angry at him?

Before my father died [in 2005], we made peace. It was fine. But I can’t say that I understood everything, or accepted it. In writing this book, I got to understand him as a man, instead of looking at him as my father who screwed up in different arenas. I ended up liking and loving him even more.

Other than your father, were there other things you had to accept in your life?

I had to accept myself. The whole journey of finding myself was quite a road. Thinking perhaps I wasn’t enough, or my name wasn’t correct, or the music wasn’t whatever it should have been.

The other thing that’s interesting is the spirit inside of me that wouldn’t allow me to take all those deals. When a teenager is being offered record deals and he’s living in a car, or living on people’s couches, not having anything — it really surprises me that I didn’t take any of those deals. Something inside of me knew to hold out.

There are striking differences between your mother and your father. She exposed you to Black music, theater and poetry. Your father, who was Jewish, doesn’t seem to have been interested in educating you about Judaism.

No, he wasn’t that kind of a communicator with me. And he wasn’t religious. As with many Jews in my family at the time, it was all about tradition and keeping that alive, especially after what people in the family had gone through in World War II. But I still got exposed to it, from going to temple and spending the High Holidays with my family at their houses.

There’s a breathtaking passage in the book that involves your father. You’re 19 or so, and you discover he’s been cheating on your mother. You tell her, and she says she already knew. Then the three of you talk, and he says something horrible to you, about cheating: “You’ll do it, too.”

Yeah. He was speaking from his truth. He ran off to the military to get out of the house, because his father had done that to his mother. And here he was repeating that. I guess he figured, “This is a generational curse that we can’t get out of.”

It was the most horrific thing he could have said. Those words burned through me. It’s taken me my life to deal with. In that situation? Tell a lie. My mother thought this was his moment to say: “Son, this was horrible. This is wrong, and I hope you learn from this.” The kind of thing you’d see on “Leave It to Beaver.” He said, “You’ll do it, too,” grabbed his bag, and walked out the front door. It couldn’t have been better directed.

On your most recent album, “Raise Vibration” from 2018, there’s a song called “Here to Love,” where you say love and nonviolence are the only ways to affect change. But in the next song, “It’s Enough!,” you seem to doubt they can work. Have you held on to your nonviolent beliefs?

I ultimately think it’s the way. But [long pause] I can see both sides. At a certain point, you feel the need to push back, because you’ve been nonviolent, you’ve been elegant, you’ve been thoughtful — and then people walk over you. Every year, every decade, I thought we were chipping away and getting to a better place, slowly. You knew there were racists, but they couldn’t be overt about it. People are losing their minds in general on the planet.

One of the record deals you turned down years ago was offered by John McClain, an A&M executive who wanted you to join a band that would be a “Black Duran Duran.” It’s a shame that didn’t happen, because it would’ve been amazing.

We were sitting in his office, and he said, “We’re going to be jet-setting all over the world, South of France, making videos like ‘Rio,’ on a boat, wearing beautiful linen suits.” [Laughs] He was selling it. But I said I couldn’t do it.

Funny, because we are very good friends to this day. He and I are both like brothers to Denzel [Washington], and Denzel got me back in touch with John years ago. John’s the one that hooked Michael [Jackson] and I up together, when I wrote and produced a song for him.

You and Zoë are very close. When she was growing up, you spent a lot of time on tour and in the studio. What kind of father were you?

Yes, I was in and out, going on the road. But then Zoë moved [in] with me when she was about 11. She went on tour with me, we had teachers on the road, I took her around the world. I think that experience, and her mother’s house, exposure to the arts, gave her a certain strength and knowledge. We’re best friends. There’s nothing we don’t talk about.

Sometimes I call too much. She’ll joke and let me know that I’m a little too much. But if I don’t call her for a few days, she’ll call and say, “You didn’t call!” I love that. You do miss me! You do love me, don’t you?!

Has the music business gotten any easier for Black musicians who want to play rock ’n’ roll?

I don’t see much of it. Rock ’n’ roll in general — where is it? White, Black or otherwise. You do see young kids on Instagram, playing electric guitar. They don’t want to hear trap or hip-hop — they want the Stooges, the MC5, Bowie, Marc Bolan. I’m sure something’s going to come of that. I’m always hopeful.

You smoked marijuana every day from the age of 11 until you were 35. Then you stopped for a while. Do you smoke now?

I smoked like Bob Marley — I was on that level. I guess now you could say like Snoop Dogg, right? That’s how I was, from the moment you wake up to the moment you go to sleep. Then I needed to come off it, and I did. I realized that life was trippy. Regular, not-being-high life was like being high. I needed to feel things, in a different way. Now I just do it when I feel it.

Here’s a psychological theory. You describe your childhood as “golden,” and say it was the happiest time of your life. Is your love for the music you grew up on also a way of holding on to that childhood?

Probably. Last night, I was on YouTube for hours, watching Jackson 5 footage, Motown, different stuff. I am very nostalgic in that way. It’s amazing work. But yes, it does make me feel a certain way. It makes me think about growing up in New York as a kid. I was watching footage, thinking: “What happened to music? What happened to romance?” We’ve lost all that subtlety.

Your memoir ends when you’re 25, and you’ve released your first album. You write, “I didn’t know then that the life of a rock star is in equal measure a beautiful blessing and perilous burden.” Is it safe to assume there’ll be a second book that gets into the blessing and burden dichotomy?

This book is about the journey of finding my voice. The next one will get real messy. [Laughs] Everything changed. I didn’t have a world looking at me, or people projecting their ideas of who I am. Then you get thrown on that world stage. What you have access to gets crazy.