Early in the summer of 1973, singer David Lee Roth and guitarist Eddie Van Halen performed together for the first time. Playing in front of an audience of buzzed students from John Muir, Blair and Pasadena high schools in an east Pasadena backyard, this embryonic version of Van Halen, then called Mammoth, blasted out songs by Black Sabbath, Grand Funk Railroad and Cream, rattling windows and shattering eardrums while party attendees chugged keg beer.

Last week, Eddie Van Halen died from cancer, at age 65, and tributes to his transformational musical contributions poured in from around the world. But long before anyone outside of the San Gabriel Valley had heard of the band, this pairing of two aspiring musicians who had little in common save their long hair drew together a generation of hard-rock-loving SoCal teens.

The Pasadena chapter of the Van Halen story begins in 1962. That year, the Van Halen family — 7-year-old Eddie, his older brother, Alex, and their parents, Jan and Eugenia — emigrated to America from Holland. They spoke no English, making the trip with a few suitcases, about $15 and the family’s treasured piano.

Jan Van Halen, a Dutch big-band musician, had in 1950 married Eugenia Van Beers, a Eurasian woman whom he met while on an extended tour of Indonesia, in Jakarta. In 1953, they migrated to Amsterdam to escape Indonesia’s political instability. Then after nearly a decade in Europe, they left Holland for the United States. According to Alex, they moved because his father believed “America was the land of opportunity” that would provide him ample musical prospects.

Years later, Eddie would remark that his father’s conception of his family’s new homeland initially turned out to be a “crock of s—.” With big band music out of fashion, his father’s first job in America was as a dishwasher at Methodist Hospital in Arcadia. Eugenia worked hard as well, cleaning houses to supplement her family’s income.

Eddie’s first experiences in America were similarly bracing. In a 2015 appearance at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Eddie recalled how his initial days as a second-grade student in Pasadena were “absolutely frightening.” As a Dutch-speaking immigrant, Eddie was, in his words, considered a “minority” and grouped on the playground with his Black classmates as part of his elementary school’s de facto segregation policy.

“My first friends in America were Black,” he said. “It was actually the white people that were the bullies. They would tear up my homework papers, make me eat playground sand and all these things, and the Black kids stuck up for me.” Eddie later emphasized the character-building aspects of this bullying, saying that for him and his brother, these soul-searing moments “made us stronger because you had to [be].”

These experiences bonded the brothers and the family. Eddie and Alex, who’d begun taking piano lessons in Holland, continued them in America. Their mother was a strong advocate for this musical education. Eugenia, who knew her husband’s career struggles better than anyone, wanted to assure that if her sons were going to follow in their father’s footsteps, they’d pursue a more respectable and stable musical path, one that would keep them out of nightclubs. Her dream for her sons was for them to become classical pianists. As Eddie put it, that drove her to “crack the whip” over lessons.

Despite their mother’s best efforts, Eddie and Alex soon became enamored with hard rock, a shift that roughly coincided with the family’s purchase of a compact two-bedroom home at 1881 Las Lunas St. in a heavily white neighborhood, just north of the 210, in the central part of Pasadena. In their new residence, the Van Halen brothers forged a tight musical partnership, with Eddie on guitar and Alex on drums. Childhood friend Tom Broderick remembers that Eddie quickly became obsessed with his instrument. “We never played football or rode bikes together, and to be honest I rarely saw him in class at school,” he tells The Times. “When I did see him, he was jamming at a party.”

By the fall of 1969, Eddie and Alex had enrolled in their neighborhood school, Pasadena High. Months later, a federal district court issued a momentous decision, holding that the Pasadena City Board of Education had violated the 14th Amendment rights of students through its segregation policies. The court ordered that by the start of the 1970 school year, no student body at any city school could “reflect” a majority of “minority students.”

In practice, this meant that Pasadena Unified School District needed to rebalance the demographic makeup of the city’s schools, including its three senior high schools: Pasadena High; John Muir, about three miles west of Pasadena High; and Blair, in South Pasadena. To address this inequality, the city developed a busing plan in which students of color shifted to the majority-white Pasadena and Blair high schools, and white students transferred to the heavily Black and Latino Muir High School.

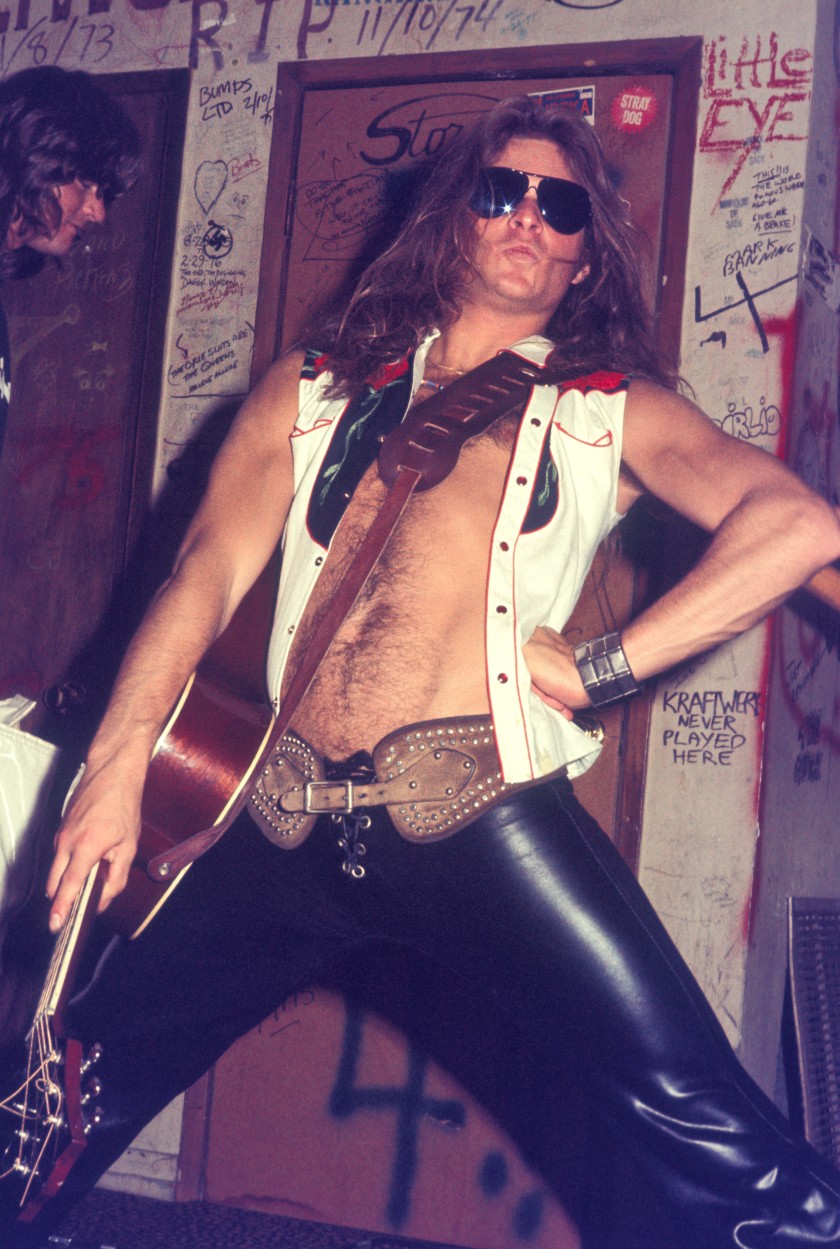

David Lee Roth in the dressing room at the Whisky a Go Go in West Hollywood, May 29, 1977.

(Lens/Estrada Media Punch)

While the Van Halen brothers would remain enrolled in their neighborhood high school, David Lee Roth, who’d moved to greater Pasadena from Massachusetts in 1963, would have a different experience. Roth, the Jewish son of a successful ophthalmologist, would be bused from the city’s south side to Muir in 1969, his sophomore year. Even Roth, who had grown up around Black people and had a longstanding affinity for Black culture, likely felt unprepared for the cultural immersion that awaited him at Muir. His high school friend George Perez explains, “At Muir, you had militant Blacks, who had Afros and Angela Davis posters in their lockers. You had longhaired white hippies and Mexicans as well.”

Roth was adept at navigating this racial and ethnic terrain. Vincent Carberry, who was tight with Roth, explains that Roth “got very good at bridging the gaps” and “getting along with everyone, whether that meant embracing Black and Spanish music, playing soccer or whatever else.”

Another friend, Dan Hernandez, concurs, saying that while Roth’s volubility made him a great diplomat, ultimately Roth had credibility in the halls of Muir because “he was basically a white dude who wanted to be Black. He had soul.”

By the time Roth graduated in 1972, he’d begun singing in a rock band. His showmanship and charisma drew a strong multiethnic following among Muir students. He’d also begun sizing up the competition, namely Mammoth, a trio consisting of the Van Halen brothers and bassist Mark Stone, at a number of backyard parties. Recognizing the immense musical talents of Eddie and Alex, he began angling for a way to join their band as lead vocalist.

At first, the Van Halen brothers were less than enthusiastic about Roth’s entreaties. Everything, from Roth’s social class and cultural style to his musical taste, turned them off. Roth’s father had money. The young singer wore flares and suspenders, a Bowie-inspired shag, and platforms. He liked Billy Preston, Sly and the Family Stone and the Rolling Stones. The Van Halen brothers were blue-collar kids who wore their hair straight and long. Chain-smoking Camels, they pioneered the grunge look long before the birth of Nirvana: They favored Pendleton flannels, lightweight cords or faded denims, and desert boots.

Most important, they had little use for the soul and funk music favored by Roth. Instead, Mammoth played the hard rock hits of the day by Black Sabbath, Deep Purple and Cream. As Roth told the Guardian in 2012, Van Halen and their Pasadena High buddies were “98% Jeff Spicoli.” Apart from their deep mutual interest in becoming professional rock musicians, they had little in common.

Ultimately, Roth won the brothers over, in no small part because Eddie, who was Mammoth’s lead vocalist and guitarist, didn’t like singing lead. Roth, however, saw more sociological factors at work, telling The Times in 2012 that the “immigrant energy” of the Van Halen family, along with his own intense drive to succeed, made them a perfect pairing: “desperate people seeking desperate fortune — with a smile.” Soon after, upon Roth’s suggestion, the band changed its name from Mammoth to Van Halen.

Although it took the Van Halen brothers’ fans some time to warm up to Roth, Van Halen inarguably became a better band with a ringmaster like Roth fronting the group. This union of talents also broadened and expanded the band’s fan base by drawing together a broad swath of fans from their respective high schools. “Backyard parties,” Roth observed in his 1997 autobiography, “developed into an art form.” From 1973-75, Van Halen would play dozens and dozens of these gatherings.

Early in the school week, enterprising hosts, often wealthy teens or young adults whose parents had decided to take a ski vacation to Aspen or a skin-diving trip to the Caribbean, printed hundreds of party fliers trumpeting the appeal of Van Halen and plentiful keg beer. The hosts and their friends then distributed the fliers across the city. “At the three different high schools,” Patti Smith Sutlick, then a Blair student, says, “the talk all week was, ‘Where’s the party this weekend?’”

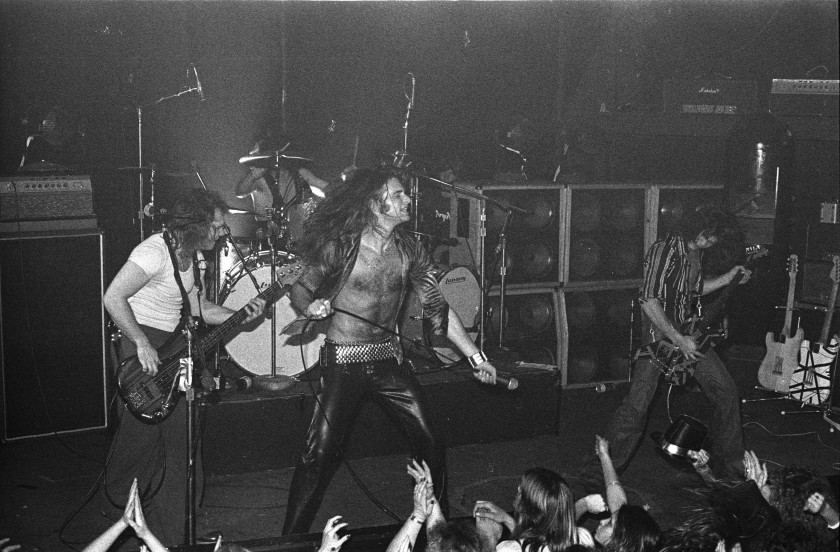

Van Halen performs at the Whisky a Go Go, 1977.

(Lens/Estrada Media Punch)

If no sure answer was forthcoming by Friday night, teenagers made a beeline for the corner of Allen Avenue and East Villa Street. Jan Velasco Kosharek, who grew up in the neighborhood, says the small commercial district there included a florist, a gas station and a very well patronized business, Allen Villa Liquor. Located a couple of blocks from the Van Halen home, it was where Jan Van Halen and his sons bought their beer. Marcia Maxwell, another Pasadenan, recalls, “We’d ask Larry, the owner, ‘Where’s the party?’ And off we’d go.”

Even if kids didn’t know the exact address, these parties weren’t hard to find. By rolling down their car windows, they could, by following the reverberating Eddie Van Halen riffs and David Lee Roth screams, make their way to the right spot. Debbie Hannaford Lorenz, who grew up in neighboring San Marino, observes: “When I hear a Van Halen song, I remember walking down the dark street with all the cars and the music echoing everywhere. My friends and I were always so excited to go to these parties.”

This kind of buzz was enhanced by the ample substances on hand. Along with abundant alcohol — whisky pilfered from parents’ liquor cabinets, Boone’s Farm Apple Wine bought at Trader Joe’s for a buck, and gallons of keg beer — drugs were readily available. During this golden age of recreational drug experimentation, there was plenty of pot, coke, acid, mescaline, peyote, mushrooms and quaaludes. As one local summarized: “What do I remember about those Van Halen backyard parties? Lots of drunkenness, lots of fun and lots of drugs.”

Art Agajanian, who hosted a monstrous Van Halen party at his parents’ Chapman Woods home in 1973, says: “It was the perfect moment in time to have these parties. Something like a thousand people came, from all three high schools: football players, everyone. A lot of relationships and friendships started because of it. ”

Fans set up a makeshift memorial near Eddie Van Halen’s childhood home in Pasadena.

(Richard Shotwell / Invision)

Van Halen’s role as house band for the Pasadena backyard party scene came to an end around 1975. After making a name for itself on the Sunset Strip, Van Halen released its debut album in early 1978, which would sell more than 2 million copies worldwide before the year ended. The band had become rock superstars.

Still, the Van Halen brothers kept living at their family’s home on Las Lunas through the end of the decade. Only after Eddie Van Halen began his relationship with his future wife, actress Valerie Bertinelli, did he move out of his childhood home.

Some 40 years later, the central Pasadena neighborhood where the Van Halen brothers grew up has changed in some significant ways. Hispanics now outnumber whites, with a growing community of Armenians in the vicinity as well. Blacks, who lived there in relatively small numbers back in the 1960s, now represent nearly 10% of the population. Michael Kelley, a longtime resident of the area, says, “This neighborhood has become much more multiethnic and wealthier as well.”

The commercial strip at the corner of Allen Avenue and East Villa Street has also experienced a transformation. The only holdover from the 1970s is the liquor store, now called M&S Liquors. On the sidewalk surrounding its entrance, a memorial of votive candles, flowers, guitar picks and chalked messages to Eddie Van Halen adorns the concrete. In time, these tributes will fade, leaving behind one permanent representation of the mark that Eddie made upon his neighborhood: a many-decades-old etching of VAN HALEN, carved deeply into the gray curb.

Renoff is a historian and the author of “Van Halen Rising: How a Southern California Backyard Party Band Saved Heavy Metal” and “Ted Templeman: A Platinum Producer’s Life in Music.”