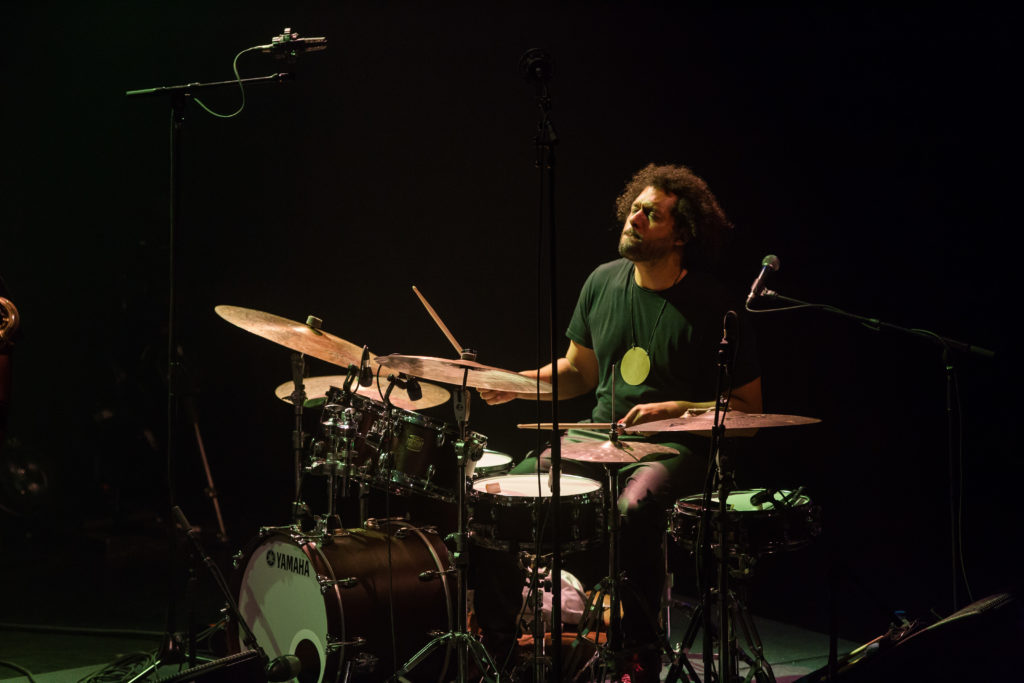

The Australian electronics artist Nick Murphy, formerly known as Chet Faker, performs at the 2019 Montreal Jazz Festival on July 2. (Photo: Alexanne Brisson)

Addressing the audience midway through his set at the 2019 Montreal Jazz Festival, which ran from June 26 through July 6, rising star drummer Makaya McCraven took a moment to reflect on his place in time. The fest was celebrating its 40th anniversary, and McCraven philosophized on the scope of that achievement: “The Montreal Jazz Fest turns 40 this year?” he mused. “Damn, that’s older than me!”

Such things are bound to happen when a festival as prestigious as this one advances into its golden years, while at the same time promoting an open-armed attitude toward young jazz pioneers like the 35-year-old McCraven. It was a case of the festival’s past running square up against its future, and it was one of many threshold moments that populated the 2019 edition, during which genres and generations collided to thrilling effect.

Founded in 1979 by André Ménard and Alain Simard, the Festival International de Jazz de Montréal, as it is officially known, has played host to a number of jazz greats throughout the years, from Miles Davis to Ella Fitzgerald to Herbie Hancock. But from the very beginning, it has also served as a showcase for jazz-adjacent rock and R&B acts. Historically, those have included Aretha Franklin, Erykah Badhu, Ian Anderson and Stevie Wonder. This year, the pop contingent expanded to comprise artists from hip-hop and electronica, which meant that rock icons like Bryan Adams, Peter Frampton and Allan Parsons shared space in the lineup with eccentric indie-rockers alt-J and electronics artist Nick Murphy, formerly known as Chet Faker.

The diversity of programming, as Menard has made clear through interviews, was intended to stress the theme of integration and progress, to show how influences from outside genres serve to invigorate the jazz tradition. It’s a winning formula, one that has helped the festival grow from a casual gathering of jazz fans in the early ’80s to one of the most recognized jazz festivals in the world.

But as the 40th edition so emphatically proved, the festival also places a premium on showcasing artists who are reinventing the music from the inside. This year’s fest featured a host of young innovators like 24-year-old multi-instrumentalist Jacob Collier, whose brilliantly frenetic, Instagram-friendly live shows drew flocks of fellow twentysomethings to the downtown Club Soda stage, as well as the 39-yeard-old accordionist Vincent Peirani, who played a medley of Led Zeppelin tunes in a style built of equal parts free-jazz and French chanson. For his part, the festival’s artist-in-residence, Roberta Fonseca, a Cuban pianist with a strong classical background, confirmed that he was among the jazz vanguard by teaming up with the New York house DJ Joe Clausell to create synthesized salsa rhythms and breakbeats in real time.

Occasionally, artists took extra-musical measures to create new audience experiences, as was the case with singer-songwriter Richard Reed Parry of the Canadian rock band Arcade Fire, who led a multi-night residency in the Société des Arts et Technologies that featured original music played in a domed room whose walls consisted entirely of video panels. As Parry and his quartet played through a heady mixture of indie rock, free-jazz and electronica, video installations were projected onto the domed ceiling, creating an atmosphere of surrealist imagery and immersive sound.

As it happened, this year’s festival was also Menard’s last, and so the theme of legacy — both Menard’s and the festival’s as a whole — figured heavily in the programming. The fest was not without its share of jazz legends. At all of 76 years of age, George Benson, who seems to have discovered the Fountain of Youth somewhere on Broadway, sang with the stamina of a man half his age to a packed house at the Salle Wilfrid-Pelletier at the Place Des Arts. And Ravi Coltrane, himself keeper of a strong jazz flame, performed with his quartet at Théatre Maisonneuve, offering up an evening of music that ascended from a hard-bop foundation into a more spiritual plane.

Dianne Reeves was celebrating a milestone of her own — the 20th anniversary of her landmark album Bridges — and her performance in Montreal provided the opportunity to share with the audience that album’s standout song, “Suzanne,” by famous Montrealer Leonard Cohen. It also gave her the chance to reunite with one of that album’s standout instrumentalists, the guitarist Romero Lubambo, and rekindle a friendship onstage.

No figure as integral to Montreal as Ménard can every truly leave the fest, and even if he isn’t directly involved in the proceedings, his imprint on the musical programming is indelible. The aesthetic balance he helped create — the deference to history, the investment in jazz’s future — has sustained the fest for four decades, and will hopefully carry it forward for many more. That aspect came to light the night Joshua Redman performed at Théatre Maisonneuve. In a ceremony before the concert, the 50-year-old saxophonist was presented with the Miles Davis Award for outstanding contributions to jazz. The presenter was Menard himself.

The episode certainly qualified as a threshold moment. Redman first appeared at the festival in the early ‘90s, back when he himself was a jazz rookie. He recalled his initial appearance as “my first festival as a professional musician,” and said that the experience “spoiled him.” He has appeared back at the fest more than 10 times since. Redman told the crowd that the award carried special significance because it was the last one that would come directly from Ménard’s hands. He acknowledged that he thought it unfathomable that the Montreal festival could exist without Menard. And yet, his assessment of the festival’s future was a bright one.

“There’s a spirit here,” Redman said. “You feel it in the street. It’s a festive festival. There’s nothing like this one.”