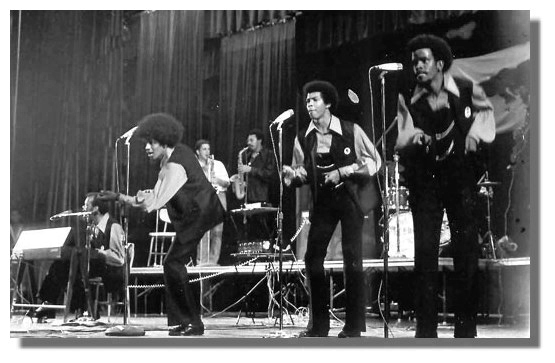

In 1970, an unlikely R&B group evolved out of the Oakland chapter of the Black Panther Party. (Courtesy of It’s About Time Black Panther Party Legacy & Alumni)

Fifty years ago, an unlikely musical group evolved out of the Oakland chapter of the Black Panther Party. They were called the Lumpen. And although they quickly gained a following for their air-tight funk and striking lyrics, they were always meant to be much more than mere entertainment.

Where other bands of their era were content to coast on good vibes, the Lumpen were out to preach a message of revolution in places where that message wasn’t always wanted. They were a musical cadre whose mission was to spread the seed of social revolution, armed with funk, attitude and matching outfits.

In 1973, Michael Torrence is a 22-year-old Black Panther. He’s dedicated himself to the cause and obeyed every command. He’s a true soldier.

“We were definitely as hardcore as anybody cause we dropped everything to come,” says Torrence. “We didn’t join to sing. We joined to be revolutionaries. We joined to make the revolution. We joined … to be Panthers!”

But five years of complete devotion to the Panthers has taken a toll. Now, Torrence is desperate to focus on his personal life, just for a while.

But to do this, he needs to get permission and it’s got to come from the top.

Torrence shows up at the Lamp Post — it’s a bar in West Oakland — where Panther leader Bobby Seale is having a birthday party. The two men huddle in a corner and talk for a while, but it’s all good.

Seale gives Torrence his blessing for some leave time.

Torrence is relieved. But as he’s making his way out of the bar, someone tells him that Huey Newton wants to see him. And he wants to see him now.

Newton is Seale’s comrade and co-founder of the Panthers. For years, Newton has been a strong and charismatic leader. But recently his moods have been unstable. Tonight, for whatever reason, he’s agitated.

Torrence is ushered into a chair in a back room. And there, flanked by a couple enforcers, is Newton.

“And he says, ‘Comrade, I hear you want to leave us. Well, do you want to leave bad enough to die? Do you really want to leave bad enough to die?’ I don’t understand the question,” Torrence says. “And [Newton’s enforcer] June takes a gun and puts it to my head. ‘Oh no, comrade, I don’t want to die.'”

“He say, ‘Okay. So this is what’s going to happen, you say…’”

Torrence starts to object. Newton isn’t having it.

“Would you tell this brother not to talk when I’m talking?”

Torrence gets a swift kick in the mouth.

Newton begins again, “Okay then. So. You say, all power to the people.”

“All power to the people,” mumbles Torrence.

Michael Torrence has just been persuaded to rethink his request for some time off — a pistol to the head is hard to argue with.

People Get Ready

By 1973, Torrence’s years with the Panthers have been a rollercoaster life of extremes. Many times he’s picked up a gun.

But he’s also picked up a microphone.

Though Torrence did not join the Panthers to sing, the movement’s Minister of Culture gave him and three other young soldiers a special assignment for the cause. It was an R&B group called the Lumpen.

When it all began in 1970, the Lumpen’s music was explosive. The band was powerful, and so was the message.

The Lumpen worked nonstop for the cause, killing it wherever they performed: San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia and the Midwest.

But it only lasted 11 months. Then things in the Black Panther Party began to implode.

This is the story of the rise and fall of an unlikely R&B group born out of social upheaval. The Lumpen weren’t out to make hit records, they were out to change American culture.

It’s a journey unlike that of any other band.

And Michael Torrence was at the center of it.

Rise of the Panthers

In 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale co-found the Black Panther Party. They’re both students at Merritt Community College in Oakland.

Within a few years, the Party offers educational programs, food service, free medical care and drug rehab to the Black community. And the Panthers are leading the fight against rampant police brutality.

By the end of the ‘60s, change is in the air, and the Bay Area is ground zero.

“[In] San Francisco at that time, we were in the Fillmore District,” Torrence says. “It was very high-tension. Police were riding, you know, four or five deep. If you were out selling your papers they would come and harass you, snatch your papers, maybe arrest you, threaten you. But at the same time there was a lot of energy. That’s the best thing about it. You could really feel the energy, particularly among younger people, that we felt we could really make a change. Not only could we make a change, we were going to make a change. There was this commitment to die if necessary.”

Those papers are the weekly bible of party information, a publication called The Black Panther. And the Howard Quinn Printing Company on Alabama Street is where the Lumpen story begins.

Former Lumpen singer James Mott, now known as Saturu Ned, takes up the story.

“Wednesday night was distribution night, where we would get out the paper. Everybody would come,” he said.

That’s in 1970: He’s newly arrived from the Sacramento Panther chapter.

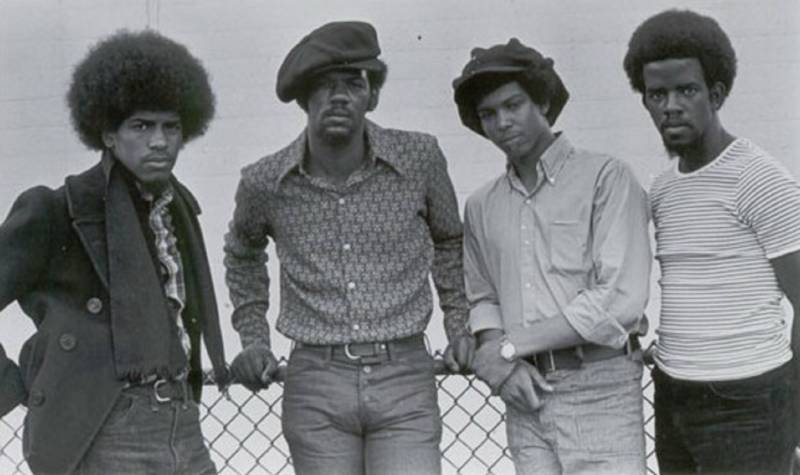

All the future members of the Lumpen are in attendance that Wednesday night: Torrence, Mott — now Saturu, William Calhoun and Clark “Santa Rita” Bailey. They all have musical backgrounds ranging from church choirs to professional-level experience, but when they meet, they’re just loyal young soldiers taking orders along with everybody else.

“It was a community gathering in Fillmore,” Saturu says. “At that time, Fillmore is not like it is now, changed, and the gentrification. It was … Fillmore.”

“And on those distribution nights when various chapters would all come together from the Bay Area to get the paper out, we would sing,” Torrence says.

“And we would sing, at that point, just doo-wop songs,” Saturu recalls. “So one night I went over there and the three of us sang and I joined in. And we started harmonizing. We just blended in so cool!”

“And then what we began to do was, we’d just put other words to the popular songs. Because we would be singing what we called revolutionary songs to encourage us in the struggle. In terms of the Lumpen, it kinda grew out of that. Just us singing together. Part of, I guess, the tradition of just singin’ while you work,” Torrence says.

It’s a typical Wednesday. The four Panthers are at the print shop, stacking and racking and harmonizing into the night. But this time, there’s someone listening: Emory Douglas, the party’s Minister of Culture.

“So after I got back to Central [headquarters], Emory comes in and says, ‘Hey brother, comrade James, you know, everybody relates to music.’ I say, ‘Yeah Emory, they do.’ He says, ‘You guys sound good. We could create a group and the group could be part of the Ministry of Culture, where we could be able to get that message out in the music.’”

Emory Douglas is the brilliant style guru and visual artist whose iconic posters and flyers helped brand the movement.

“I just would make suggestions,” Douglas says. “Possibly adding some social justice context to the lyrics.”

At this point, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton are both behind bars. So Douglas approaches Panthers Chief of Staff David Hilliard. He understands the value of spreading the word through music, and he greenlights the project. He also gives the group a name: The Lumpen.

It’s a play on Karl Marx’s idea of the lumpenproletariat: the lower class that would rise up to crush the capitalist power structure.

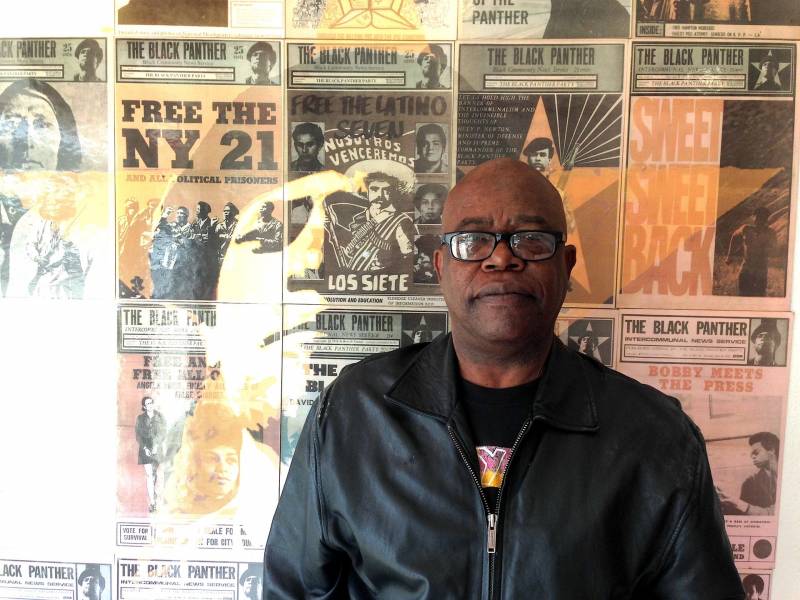

“At the time the party was coming about, political education, political awareness, was growing tremendously,” says Billy X Jennings. He’s a former Panther and the party’s long time historian. He was tight with the Lumpen members fifty years ago, and still is to this day.

“In 1968, James Brown put out a song that really changed everything, because Black people, prior to that time, referred to themselves as Negro,” Jennings continues. “James Brown came out and said, ‘We’re Black and we’re proud.’ And once that record come out, you could never go back and say you’re a Negro. You could never go back! James Brown couldn’t have did that in ‘68 if there wasn’t a group like the Black Panther Party that had set up a foundation of knowledge already.”

“Emory was recognizing the role of music historically in Black people’s struggle and part of our culture period,” Torrence says. “He began to say, we can do something with this! You guys sound decent together anyway, because we just clicked like that. And so he encouraged us to put something together.

“Whatever rehearsal we would do, we would have to do after whatever other assignments or duties we had,” Torrence continues. “So we had to go sell the papers, we had to do the breakfast program, we’d have to do the garbage run, we’d have to do security. We’d have to do whatever it is that any other Panther would do.”

From the Panthers’ perspective, The Lumpen was not about show business. It was about contributing to the revolution.

“Singing for us was just political work,” Torrence clarifies. “And if they said the next day, ‘Okay, that’s it,’ fine. Cause we didn’t join for that. If I was really about that, I could have been trying to do it out there in the world. I could have been out there trying to get paid. We never got paid, it was just, if this is how we can be helpful, if this is how we can be useful, if this will advance the cause, this is what we’ll do. But it was always, we follow orders.”

And now, only a few months since they were harmonizing to the oldies at the printing plant, their orders are to get onstage and get to work: Educate the people, spread the word and earn money for the party.

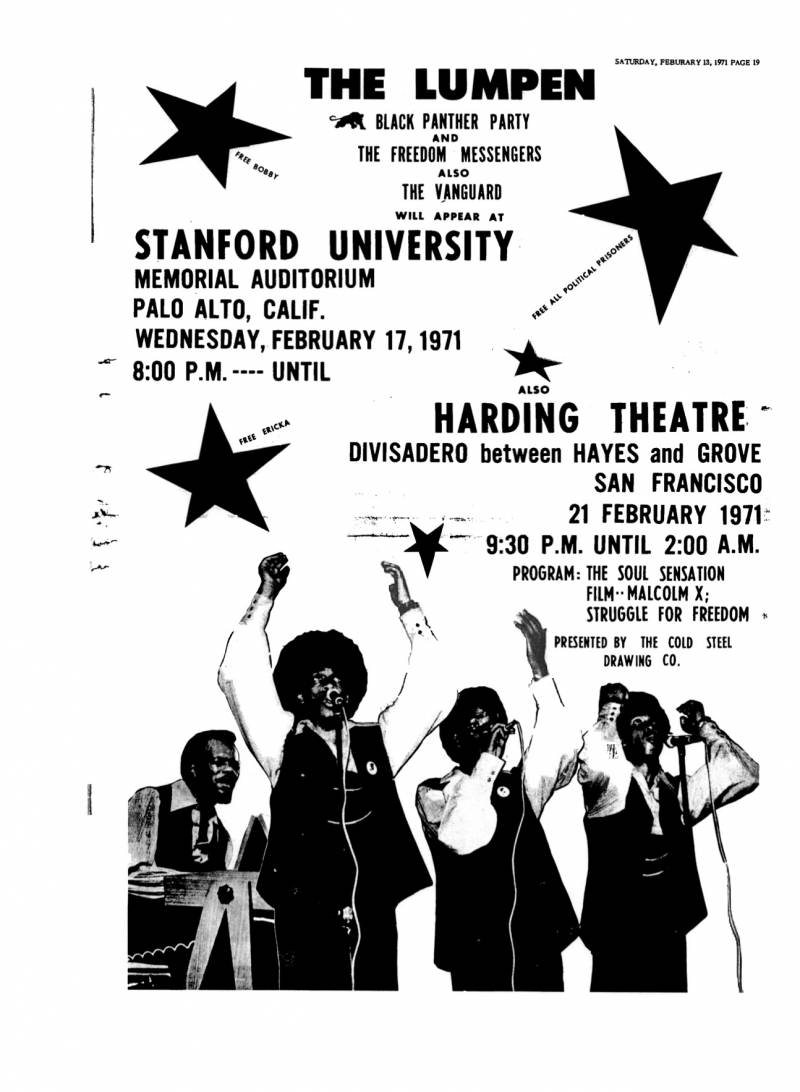

The Lumpen assemble a six-piece interracial backing band from local players sympathetic to the cause. They’re called the Freedom Messengers.

By the summer of 1970, the group is performing at rallies, community gatherings and Panther events around the Bay Area.

And they’re good. They’re tight. It’s a professional show on par with almost any act. They’ve got the energy of James Brown, and the dance moves and harmonies of the Temptations. But the lyrics are all about what the Panthers are all about.

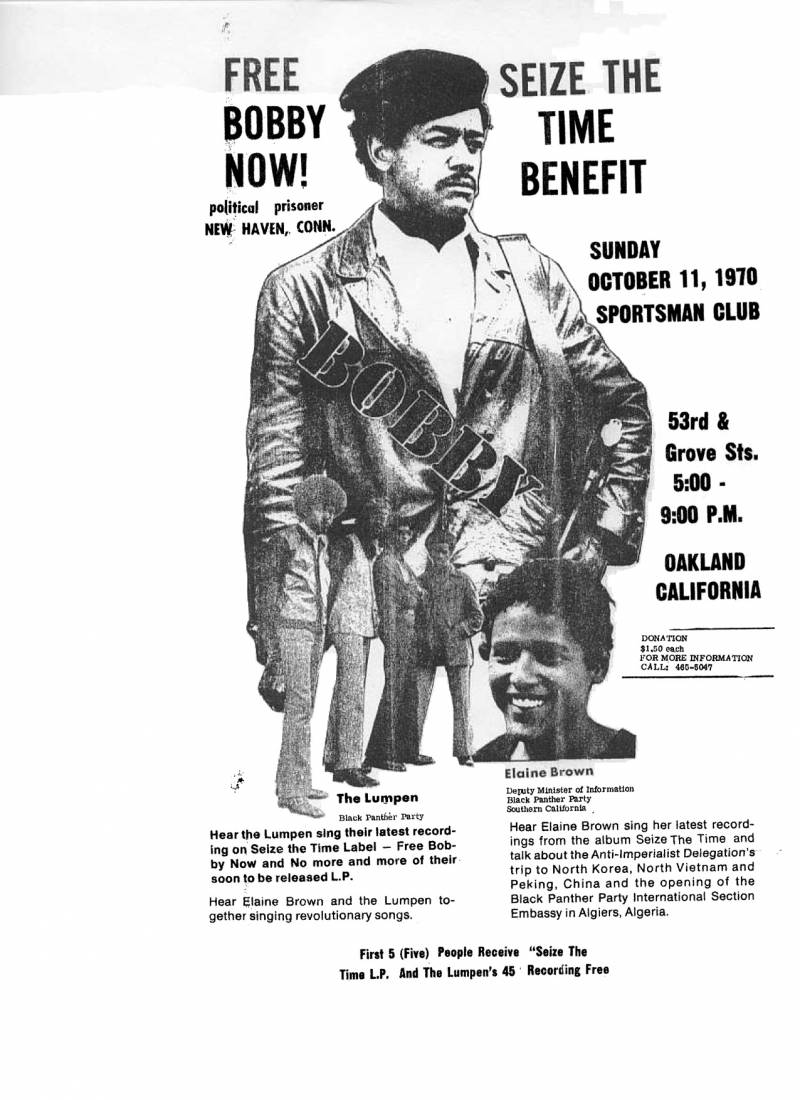

Bobby Seale has just been arrested in New Haven. The first and only single the group makes is “Free Bobby Now.” It’s written by Bill Calhoun, recorded at Tiki Studios in San Jose in August of 1970. Calhoun’s song “No More” is on the flip side.

The record is released on the Panthers’ own Seize the Time label, with credit to Black Panther Party Productions. It’s promoted in the Party newspaper, and sold at live shows and Panther events. Any profits are funneled back into the party.

The Lumpen take the single around to Bay Area radio stations, but the lyrics are considered too provocative for airplay. But no one questions the quality of what they’re hearing.

“They took the craft seriously,” says Rickey Vincent. He’s the author of “Party Time: The Inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band” and “How Black Power Transformed Soul Music”. It’s a subject he knows well. His mother was an early Panther.

“When they did ‘People Get Ready’ by Curtis Mayfield and The Impressions, they hit those notes that you had to hit that show respect for those aspirations that were in that song in 1964-65. The Lumpen flipped the lyrics, obviously. Instead of saying ‘People get ready there’s a train a’comin’,’ they said, ‘People get ready, the revolution’s comin’, you don’t need a ticket, you need a loaded gun.’ And it was like, wait a minute, that’s soul music the way it’s supposed to be sung, but those are not lyrics the way we’ve heard them before.”

The Lumpen start headlining shows. They’re gigging weekly, doing benefits and playing college campuses up and down the West Coast. And when they’re not headlining, they’re on bills with the Grateful Dead, Carla Thomas and Curtis Mayfield.

And not only is the music on fire, but the live show takes choreography to a whole ‘nother level.

“Once we hit the stage, [it was] nonstop,” Torrence says. “Even mixed in a dance routine where we would act out brothers on the block playing dice, and James Mott would be a cop. He’d come and harass one and he’d be beating this brother up, and he’d be beating him with a club and I’m watching it, and then I’d finally get disgusted and I’d jump on the cop and Clark and I together, we’d beat the cop down. So it wasn’t just the singing, it was the choreography. The whole experience was something they hadn’t seen before.”

In the winter of 1970, the band hits the road for a tour of the Midwest and East Coast. The crowds are enthusiastic. But tensions are running high.

David Levinson is the Freedom Messengers’ 19-year-old sax player. After a show at the University of Minnesota, a snowstorm is kicking in. The band is packing up their gear when they’re approached by members of the Black Student Union.

“I’ll never forget this,” Levinson says. “They invited the Black members of the band to stay with them, but they didn’t want the white members of the band, of which there were two of us.”

“These guys from the student group come out and they look like a military junta,” says Saturu Ned. “[They] got on the black berets and the black boots. I’m like, ‘What are you guys doing?’ ‘Oh, uh, who are those white guys?’ ‘Excuse me? They’re a part of the Lumpen band.’ ‘Well, they can’t stay!’ We told ’em, ‘Look you motherfuckers, we’re not staying if they’re not staying.’ I said, ‘This is a people’s revolution and these are our brothers that we stand behind.’”

Levinson is still close with Saturu and the other former band members. “That’s just a small example of the kind of camaraderie and unity we felt. There never was any racism promoted for or practiced by the Black Panther Party at all.”

The Lumpen are also in the crosshairs of the cops wherever they go. Late one night after a college show in New Jersey, the police follow the band down an empty road heading out of town.

“They made us get out the car,” Saturu says. “They knew who we were and it was pitch dark where they pulled us over. We were like, this is it. They gonna kill us. There was a general rule back then, go to a lighted area. What they did was, one car got in front of us, slowed down. The other one got right behind us. And they waited for that real dark area to pull us over — this is part of the intimidation, right?

“There were four of’em. They was grinnin’. ‘Sing for us!’ So we started singing—what was that song? ‘As we stroll along together…’ They would harass us to let us know, we watching you. We know who you are.”

But the Lumpen are battling another force besides the authorities. And it’s coming from within the party.

“There were people in the party, some in leadership, some in the rank and file that said, ‘Yeah, these guys [in the Lumpen] think they’re something special,'” Torrence says.

“If it wasn’t for Emory, I don’t think the Lumpen would have came about because Emory is the one who had the juice,” Billy X Jennings emphasizes. “And there was people that wasn’t into the Lumpen. They didn’t think revolutionaries should be doing that kind of thing. But they were older people too, there weren’t R&B people, they were blues people, and during that time there was a difference. Most of the leadership was southern guys. Southern guys like blues. We are young guys, we like R&B. So that’s why [the Lumpen] never really got any more higher than they were because they were always related to as Panthers first.”

But that didn’t stop them.

On Fire in Oakland

It’s Nov. 10, 1970, at Merritt College in Oakland. It’s the alma mater of Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. The birthplace of the Black Panther Party. Tonight, to a packed auditorium, the Lumpen will get the message out.

Bear in mind: this group has been together for less than a year.

While almost everybody else in the San Francisco music scene has been getting high and jamming, the Lumpen have been working as full time revolutionaries, pursued by the police and the FBI.

And they still find time to get this group together.

And tonight is special. The show is being recorded for a live album, and the group pulls out all the stops. Billy X Jennings is there with his fist in the air.

“It was one of the best shows in my life because the audience was electrified. Once the Lumpen came on and the band start playing, you would hear them repeat something to the crowd and the crowd would throw it back. Like when they say, ‘All power to the people,’ the crowd would say, ‘All power to the people!’ with a force! And when they’d say, ‘Death to the Fascist pigs,’ they’d say, ‘Death to fascist pigs!’ If you just listen to the people’s feedback alone, you could get high on that. They were killin’ me boy! And even to this day when I hear that, it gives me that revolutionary enthusiasm cause everybody was on the one that night. We were thinking about the same thing — revolution.”

The show was an undeniable success… but no album ever appeared.

The master tapes made that night went missing, and have never been found. Some have suggested that they were confiscated by the FBI. It’s also possible that they were mislabeled and disappeared in the chaos and discord of the time period. Or they could be decaying in an attic somewhere, long forgotten.

Only a grainy, multi-generation cassette of the show has ever surfaced, but it captures the raw power of the band.

As 1971 arrives, the Panther Party leadership is in chaos. Bobby Seale is still in prison in New Haven. Eldridge Cleaver, the Minister of Information, has fled to Algeria to escape an attempted murder charge on an Oakland cop. The FBI is working to weaken and target the party through a secret counterintelligence program.

The party is factionalizing.

“Huey’s come back out with some different ideas about how things should go,” Torrence says. “In some cases you got Panther against Panther, whether you with Eldridge division or National Headquarters.”

At this point, Eldridge is strongly promoting violence.

“Right,” Torrence says, but “Huey and Bobby were moving toward a survival program. Even we had to change because all of our original songs was about picking up the gun. There was some other things going on internally, in terms of some of the things being done by Huey that I didn’t agree with, I didn’t join for. And it wasn’t about the police. That was the thing that was bad about it. I was never scared about the police. It’s a bad thing when you get more concerned about the people that you work with than you do with the cops.”

As the atmosphere within the Party becomes more desperate, interest in the group from those in power dwindles to nothing. The Lumpen members are reassigned. They’re taken off R&B duty and put on security detail. Their days as a group are numbered.

“No, it wasn’t justified,” says Emory Douglas of the group’s demise. “It could have been worked out, but you know we had people who wanted to exercise their position, as far as being in charge. All those things played into it, petty spitefulness. All that.”

As Torrence said earlier, if the day came when the singing had to stop, fine. That day finally came.

“We never thought of ourselves as anything other than Panthers. And the Lumpen was a cadre, a unit for a cultural purpose. We loved it, we enjoyed it, but in the big picture, it’s just another assignment. And so when the situation and circumstances change, then you move on to the next assignment. And we didn’t really have time to mourn about it. Because that’s exactly what happened.”

On May 23, 1971, in Sacramento, the Lumpen play their last gig. A few days later, Bill Calhoun decides to leave the party. He was the group’s songwriter. So only 11 months after it began, the band is done.

But the Panther Party is still Michael Torrence’s life. It’s all he’s known since he was a teenager. Which brings us back to that night in 1973 at the bar in West Oakland: The night Torrence talked to Bobby Seale and asked for some time off from the Panthers.

“So anyway, I go to Bobby at his birthday party at the Lamp Post and I said, ‘Well, Chairman, I have a daughter. She needs some support. Plus, I’m having these little anxiety attacks that’s affecting my work, it’s affecting my effectiveness. I don’t wanna quit, I don’t wanna leave, but I need some time. Get myself back together, and then I’m coming back. I’m coming back.’ And Bobby was real cool with me on it, you know. And I’m crying. I’m shedding tears.”

Torrence is leaving the bar when Huey Newton calls him back upstairs. He says the Party will contribute $50 a month for to support Torrence’s daughter. Then Newton puts a gun to Torrence’s head and says this:

“’Okay then,’” Torrence recalls. “’We send fifty dollars, but you say: All power to the people.’ All power to the people. So I stuck around.

“And about six months later, one of the guys from Chicago comes by, says, ‘You still wanna go? Cause we can’t afford to pay for your kid no more. So you can go, you can leave now.’ OK. Well, all right then. Power to the people now.”

And that’s it. Michael Torrence is out of the Black Panthers.

Related coverage

“And it was traumatic,” he says. “What was traumatic for me was leaving. What was traumatic was what it had become.”

Did he feel betrayed?

“Yes! Absolutely. Betrayed, angry, bitter, frustrated. Yes. It took me a while to get back to what they call livin’ in the world. ‘Cause the Party was my world. You ask me what I was, I was a Panther. That’s what I was and who I was. And then to lose that … and try and adjust to out being here, and get a job. What am I gonna put on my resume? Where you been the last five years?”

But Torrence did have something on his resume that worked outside of the revolution: The Lumpen. It got him a job.

Torrence wound up singing behind Marvin Gaye, and he appeared on the singer’s 1974 album, “Marvin Gaye Live!” It was recorded just a few miles away from where the Lumpen recorded their own live album just four years earlier, in Oakland.

Torrence went on to write, produce and sing for other artists for the rest of the 1970s.

Though he parted ways with the Panthers almost 50 years ago, it’s still part of him.

“As far as the Black Panther Party’s concerned, I don’t regret anything,” he says. “I was with people, [and] these things last a lifetime … and I wouldn’t take that back for anything. Did we make some mistakes? Yeah. But at the time, for what it was, it was right on time. I was just glad to be a part of it. Like I said, we never did it to get famous, we never did it to get rich. We did it because we really wanted to do something for our people, and make a change.”