For his latest Behind the Curtain entry, rock journalist Steve Rosen recalls meeting one of his heroes, Arthur Lee of Love, for a Rolling Stone interview in 1975 — and what about Lee and his music had such an impact on Rosen throughout his life.

It is July 1966 and I’m not yet 13 years old but I’m already a geek, a dork, unpopular and feeling like I’m living in someone else’s body. At school, other kids my age have already sorted out who they are. The girls with beautifully straight and lustrous hair and the boys with perfect smiles and straight teeth and outgoing personalities are socs, (rhymes with gauche) as in socialites. They are the popular ones, the ones everybody likes. They all have lots of friends and interact easily with one another. Later in life they will end up marrying young, leading dull lives and working at mind-numbing jobs but as 13 year olds, they have it going on.

Then there are the tougher kids. Neighborhood bullies. They terrorize me and threaten me and call me names. I hate them. These fuckers will end up robbing liquor stores, shooting heroin and doing time. Serves them right.

Finally — this is not a perfect science here and I’m no child psychologist or whatever so bear with me — there are the would-be hippies. Little girls with painted flowers on their impossibly rosy cheeks and boys with perfectly layered hair wearing headbands and moccasins. I desperately want to be a hippie but my hair doesn’t grow that way and I don’t have any moccasins and I wouldn’t have the nerve to wear a headband on a dare.

So, I’m on the outside and I’m only 13 and I want to feel like I’m breathing the same air as everybody else, so how do I do that? By listening to the songs that come out of my little transistor radio. I hold onto it like it is some sort of Book of Secrets and if I place it against my ear long enough, I’ll eventually find out who I am. I don’t, but that little radio is one of the only things that sort of connects me to the world, and when those songs go tumbling down the corridors of my ear canal, I can be anybody I want to be until that song is over.

For those 180 seconds — most songs back then were typically three minutes in length or under and though FM radio had started 30 years earlier, it would not be truly felt until this period in the mid-1960s when songs would soar past the three-minute time limit and indeed entire albums would be played top to bottom — I was tuned in, man.

I was king of the hippies. I was the emperor of all hippie socialites. I was popular and my hair was straight and not kinky and I wore headbands and I had so many friends clamoring for my time and inviting me to their little birthday parties and stuff that I actually had to write down all my engagements in a little book. My little red book.

Of course, none of that really happened — but it didn’t matter. For those few minutes, I wasn’t a geek and outcast. I was somebody else, and that was enough.

One of the songs that transported me to that wonderful place inside and outside my head was Love’s “7&7 Is.” Holy fuck, I loved that song. It was frantic and dangerous and the guitars were buzz saws and the drums were bulldozers. When I heard the first three seconds of the song, I was instantly transported to a magical place where girls actually talked to me and I was kicking the shit out of every little fucker who had teased and bullied me. I wanted to stay in that space forever, but 2:20 later it was over and I was forced to come back to earth and realize I wasn’t Superman and that the next day at school I’d be tortured all over again and become the sad, lonely, unpopular kid who sat by himself at lunch.

When I think back on that song and how it provided a soft place to land, I always imagined that the guy singing the song — I had no clue back then his name was Arthur Lee — had written the song for me. Well, about me. I knew he hadn’t, of course, but I thought maybe he had. Maybe he had heard about this little kid who was being emotionally tortured on a daily basis — and sometimes threatened with adolescent violence because he was forever being challenged to fight — and wanted to help me maneuver through the labyrinth of my youth. Though I had no real understanding of what he was saying, this singer knew what it felt like to be ostracized. To be an outsider looking in; to feel like you were falling in on yourself.

I really didn’t pay much attention to lyrics generally but I do remember always singing along with this song. The first line was, “When I was a boy I thought about the times I’d be a man.” I did think about that. I thought, “Oh, shit. If it’s this bad now, how terrible will it be in 10 years? Twenty years?” I couldn’t understand the second line but the third line I knew was about me: “In my lonely room I’d sit, my mind in an ice cream cone.” I didn’t know exactly what “… sit my mind in an ice cream come” meant but I sure as fuck knew what a “lonely room” was. I lived there. I was trapped there.

I loved the singer because he was hurting and probably never had any girl ever talk to him either. He was me but much more. He was a singer in a band and he was on the radio and the music he made touched me somewhere deep inside and the words, oh man the words, were perfect distillations of my own life.

I couldn’t get enough Love in my life [sometimes Love is all you need] and that feeling grew. About a year after “7&7 Is” became my mantra, Love recorded Forever Changes and my world was impacted all over again. “Live and Let Live” became my new time machine to a place of safety and security. This singer was singing about being lonely and man, did I understand what that meant.

Everything eventually got sorted out as it usually does. I graduated high school in 1971 and was no longer on the receiving end of taunts and put-downs. I began writing shortly after leaving school and though I still felt a sense of insecurity and lack of self-confidence — a fucking curse I’d never rid myself of — meeting my heroes and writing about them was about as great a panacea as I could have ever wanted.

Imagine then how my head exploded when in 1975 I had the chance to actually meet Arthur Lee. The “7&7 Is” singer, the freaking genius who wrote, “Oh, the snot has caked against my pants/It

has turned into crystal,” the opening lines of “Live and Let Live.” Propelled forward by equal parts terror at sitting in a room with him and adulation, I contacted Rolling Stone. Though I had only been writing for a couple years, I had already written my first story for them — a feature on Bad Company — and I thought there was nobody on the planet more capable of understanding who Love was than me, so I gave the paper a shout a second time.

Rolling Stone said yes and now I was terrified times two: Beyond the insane pressure of sitting face to face with Arthur Lee, I had to confront the brain-crushing knowledge I was doing the story for Rolling Stone.

The interview was held at an office building called Crossroads of the World located at 6671 Sunset Blvd. This was the home of RSO Records, Arthur’s label at the time. Reel to Real, what would be Love’s final album, had been released in December 1974 and this was one of the reasons Arthur wanted to talk.

I was escorted back to a conference room where I carefully set up my cassette recorder and plug-in microphone. My head was filled with whispers and roars and the hollow voices of ghost memories. I thought about the dude I was about to meet and how I had listened to his music over and over and how brilliant he was and the way he tossed me a life vest when I was drowning in the turbulent seas of my own insecurities. I thought about all of that when he came bopping into the room.

Arthur freaking Lee. He was a gangster, hipster, hustler, storyteller, sage, survivor, savior, villain. His head was shaved and he was spooky, his clothes were mildly unkempt and a thin moustache sprouted from his upper lip. I rose to say hello and his eyes narrowed, staring at me like a wary creature unsure of the thing in front of him. His body coiled and uncoiled as if in preparation to strike. His head darted back and forth and he mumbled beneath his breath. He was not high but acted as if he was.

Out of nowhere, he addressed the tape player sitting on the table: “I don’t like violence,” he said, “but I love to fight.” Holy fuck, what did that mean?

When he finally sat down, the singer emitted a mad cackle, which would be the first of many. It was startling in its intensity and scared the shit out of me. I’d learn that the crazy laugh was a warning sign, which came out when I hit on something he didn’t want to talk about. When Arthur laughed, there was nothing funny about it.

He nodded to the record company publicist sitting in the background to cue up the Reel to Real album. When it came pouring out of the monitors, he said, “It’s an R&B-type thing and pretty funky. I’ve got to see if people are going to dig my trip.”

For the next hour-and-a-half, Arthur laid out his life for me. There were moments where he went off on tangents and I could barely understand what he was saying but mostly he was the coolest cat on the planet and I never wanted the conversation to end. I wanted to tell him how much his music affected me but I don’t know how to do it without sounding like a goofball and ultra-nerd.

I thought Arthur dug the conversation, or at least he seemed to. Every time I thought I should bring the interview to a close, he kept talking. I wanted to scream, “See all you fuckheads who made my life a misery when I was a little kid. Here I am sitting here with Arthur fucking Lee and what are you doing? You’re sure as shit not interviewing Arthur Lee? Who gets the last laugh?”

I walked out of there and I was Superman. Insecurities gone. Self-confidence soared like an eagle.

When I think back on that day all these decades later, I immediately jump to, “Oh, I wished I had asked him so much more,” but that’s the way I always feel after talking to one of my heroes.

The story appeared in Rolling Stone and though it was a short piece, it was fantastic.

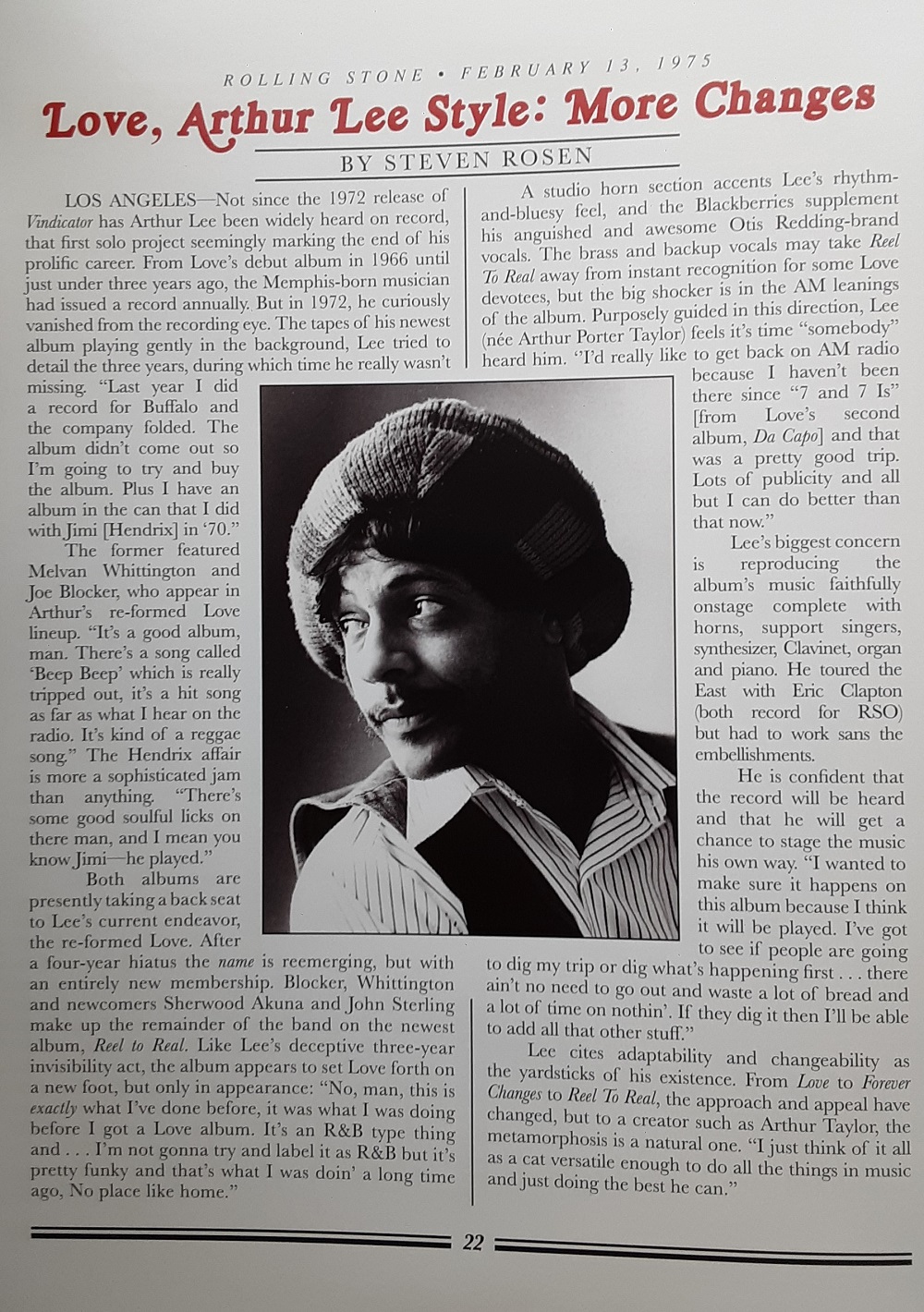

Steve Rosen’s Rolling Stone piece with Arthur Lee

I loved being in that room with Arthur. My heart rate was racing like a hummingbird’s and I was probably visibly shaking from the surge of adrenaline running through my veins, but I was in the moment. What I remember about the conversation is as much as he imparted a sense of bravado and pride when he talked about his music, there was also a sense of uncertainly about his own worth. I understood that part. Arthur Lee was really fragile underneath it all.

He would never enjoy the success of contemporaries such as the Doors, Buffalo Springfield or the Byrds but in my mind, he ate all of them up. Love had no peers.

Around 2005 or 2006, I was nosing around the Internet when I wanted to buy some Love CDs — I had all the albums on vinyl but I’d sold them years earlier — and found a page dedicated to Arthur. The website talked about Arthur’s illness, which I hadn’t known about, and it brought me to my knees. They were looking for donations for his treatment — you want to talk about how unfair life is and how this guy who was one of the greatest songwriters ever couldn’t even afford his own health insurance — and so I sent in $100. Not much.

There was a contact name on the page and I wrote to this person and told him I had interviewed Arthur and how life-transforming Lee’s music had been for me. He said he thought Arthur would really dig listening to the interview and could I make a CD copy and send it along? I copied the entire 90-minute conversation and sent it along and really never expected any kind of response.

Two days later, I heard back and this person said Arthur had listened to it and really liked the interview. This friend of Arthur’s said how particularly open Lee had been with me that day and how he must have felt comfortable with our conversation.

This touched me so fucking deeply. The idea that Arthur Lee was listening to my voice was more than a little surreal.

A month after I sent the CD, Arthur Lee passed away from leukemia. I cried.

I began a strange ritual after his passing: I’d smoke a joint — I never smoked but it seemed imperative for this experiment — and cue up a Love album on my Zune mp3 player. I’d then stroll around the various paths and lanes dotting where I lived in Laurel Canyon, earphones tugged snugly into my ears and volume turned to max.

Arthur had lived up in the Hollywood Hills for a time and I’d pretend I was on some pilgrimage. I wanted to find the exact places on the dusty paths where Arthur might have walked. I’d pick up rocks along the way and think, “Did Arthur touch this rock? Was he holding it when he came up with the line, “When I was a boy I thought about the times I’d be a man”?

Silly and stupid. I know. I just didn’t want him to be gone. I wanted him to still be here and wanted to conjure his spirit. I wanted it to be 1966 again, when he was 21 years old and in the middle of his creative salad days.

I couldn’t bring him back, but I did revive him in a small way recently. My friend Irene Okuda told me about a film being made about Laurel Canyon and that I should contact them and let them know I’ve lived here for 40 years and had some stories and done some interviews with musicians who’d spent time here.

I did, and the filmmakers ended up using a brief audio snippet of my Arthur Lee interview in the recently-released two-part docu-series titled Laurel Canyon.

Arthur Lee was a strange cat. He was as gifted as anybody could ever be but there was a part of him that never thought so. He was insecure and lacked self-confidence in a way I totally understood, which is maybe why I so identified with him. Arthur was fragile inside — which is why he presented such a tough outer façade to protect all those delicate inner feelings — and was easily broken. Maybe that’s exactly what made his music so glorious and his own life so chaotic.

He had self-doubt and was uncertain about who he was. More simply, we all loved Arthur Lee more than he loved himself.

And nobody loved him more than I.