Throughout the years, music has been an integral part of social movements. WUSA9 took a look at the history of music in social movements and its current impact.

WASHINGTON — From the negro spirituals sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers in the 1870s to popular socially conscious music of the 50s, 60s and 70s, from artists like Curtis Mayfield, Nina Simone, and Marvin Gaye to contemporary artists like Kendrick Lamar and the DMV’s own Raheem DeVaughn – music has been used to inspire change and advance social movements.

WUSA9’s Ariane Datil takes a look at how the music of Black social movements has evolved throughout the years.

Let’s start back in the 1920s with James Reese Europe’s 369th U.S. Infantry “Hell Fighters” Band playing How Ya Gonna Keep ‘Em Down On The Farm?

“How ya gonna keep ’em away from harm, that’s a mystery They’ll never want to see a rake or plow And who the deuce can parleyvoos a cow? How ya gonna keep ’em down on the farm After they’ve seen Paree’?”

“Nobody thought that anybody would be interested in Black music, outside of black circles, Kevin Fellezs, an ethnomusicologist at Columbia University said.

Fellezs studies how music shapes communities and influences cultures, specifically, African American communities.

He explains how Black culture was hijacked from African Americans – by white people, used to create false narratives about Black culture, but then ultimately and incredibly, used to shape the narratives of civil rights movements that fight for the reclamation of Black freedom and culture.

According to Fellezs, James Reese Europe was the first Black commissioned officer in the US Army.

“His job is to… keep the morale of the troops up. And so they give them this brass band,” Fellezs said.

He says the band, comprised of other Black soldiers from World War I, found so much success in France with their jazzy sound that a major record label in the country recorded some of their songs, including How Ya Gonna Keep ‘Em Down On The Farm? and “they became stars.”

“It was this huge hit,” Fellezs said.

But, he says that success didn’t translate back home in the United States where Jim Crow was still strong. And he says the frustration that the soldiers felt propelled them to press for equity at home.

“They said ‘we’re going to start demanding full citizenship,’ Fellezs explains. “That sort of becomes an impetus that grows through the 40s and again in World War II… that begins to build towards the civil rights movement. “

While artists like Europe were using their music abroad to share messages of discontent with the way African-Americans were being treated in the United State, Fellezs says gospel music is growing in popularity.

“The other thing that’s happening is gospel music, which is becoming a real force through the 30s and 40s in Black churches, and it gets picked up in the 50s as part of the Civil Rights Movement again because the churches are the spaces in which a lot of organizing is going on,” Fellezs said.

One of the groups grown out of the church was the spiritual performing Fisk Jubilee Singers.

“In spirituals, one of the roots, if you will, of gospel music, there was always a political edge to the music,” Fellezs said. “So, Wade in the Water, a classic spiritual song was really a set of instructions [for runaway slaves] on how to avoid the bloodhounds that were on your trail. So these kinds of hidden messages in those songs were always there.”

And it was through those spirituals that Fellezs says, Black artists were able to inspire large groups of music listeners to move toward action. Action that they hoped would eventually lead to equity for African Americans.

But there would, of course, be more battles to fight.

“On one hand you have the abolitionists and, on the other hand, you’d have these blackface minstrel groups that are kind of reinforcing and reproducing ideas about blackness.” Ideas that Fellezs said made an implicit argument against Black freedom.

“Whites actually thought this was real Black culture,” Fellezs said. “[But it] was being performed by predominantly Irishmen in the early years, in blackface, who were saying that this is authentic Black culture. And promoting it that way. And that’s why the kind of stereotypes around Black people get cemented.”

And according to Fellezs, it was the Fisk Jubilee Singers that were able to successfully combat those false representations of Black life.

“The Fisk Jubilee singers offer this other kind of music and this other kind of representation of Black life and Black interiority, that opposes the kind of broad, demeaning stereotypes that were being presented on the blackface minstrel stage,” Fellezs said. “And so it’s…implicitly political instantly.”

It was the 1870s when the Fisk Jubilee singers hit the stage. And according to Fellezs, that’s the first time that African Americans were able to use their music to start promoting Black freedom and equity to the mainstream audience.

But, as we saw with James Reese Europe’s band, it certainly wasn’t the last.

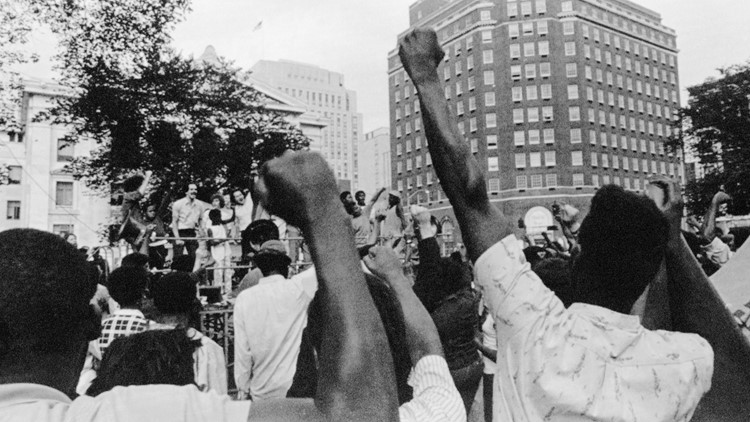

GALLERY OF PROTEST SINGERS THROUGHOUT THE YEARS

Social movement singers & activists

According to the Fellezs, “one reason music is used so much by social movements of any stripe is because of music’s sort of inherent emotional, as well as intellectual connection with people. And sort of bringing into consciousness for people, you know, ideas and maybe political situations they might not otherwise have thought about necessarily.”

“It seems like from birth I was cursed with a guilty complexion. Can’t even walk the streets in peace without the fears of being arrested. Now the community is divided we dyin by thousands from this virus. Cities in shambles and riots like when Marvin used to say: ‘What’s going on?'”

Grammy-nominated R&B singer Raheem DeVaughn is known as The Love King for his sultry ballads like Woman and Customer. But years ago, after the success of his debut album, the High Point High School graduate, faced a crossroads in his career. He asked himself: do I make the music that people need to hear right now? Or do I make the music that we think people want to hear?

“For me, it’s a conscious decision,” says DeVaughn. “I made a decision long ago as an artist that I want my music to be something that is historic, timeless, and evokes change but also has the energy of love.”

It’s a choice that many famous Black musicians have had to grapple with in the past. Artists like Stevie Wonder, Earth Wind, & Fire and Marvin Gaye who had to weigh the cost of making the music that could inspire change for Black people.

“So what’s really important about Marvin Gaye, that recording, in particular, is he had been, sort of a conventional romantic soul man, right?,” Fellezs said. “And in 1970 he approaches Barry Gordy says, ‘You know I’ve written these other kinds of songs and, you know, tide is changing. I don’t know, if romantic love songs are really what the public is wanting to hear.’ And Barry Gordy was like – ‘No!’ He’s like, nobody wants to hear social conscious music, especially coming out of Motown.”

It was that fight for what was right that inspired DeVaughn to make a similar choice decades later.

“Marvin Gaye fought for the integrity of making a record, like ‘What’s Going On’ when the label told them that they didn’t feel like it was a wise move,” DeVaughn says as he sits in a recording studio in Maryland working on his next album.

“It’s the same reason that I put out the album I put out 10 years ago: Love and War Masterpiece,” DeVaughn said. “When I was told that that wasn’t a wise move for me, you know, having such a successful career at that time, but you fight for what’s right. You fight for what matters.”

“So when you get to the civil rights movement in the 50s, there is already this kind of awareness and sense of using music to press for the social agenda,” Fellezs said. “And so, in the same way, that the Fisk Jubilee Singers singing outside of Black spaces sort of makes white America aware that Blacks have this whole musical tradition, the civil rights movement, when they bring gospel music outside of Black churches, [builds] awareness outside of Black spaces around the civil rights movement, there is this kind of precedent already.”

A precedent that allowed artists like DeVaughn to use his music to hopefully impact another generation of social change.

“The music that I make, it’s bigger than me, it doesn’t belong to me,” DeVaughn said. The goal of my music is to create a space that “brings people together and making love and but still also fighting for justice and equality.”

A message that is clear in, “Marvin Used to Say,” the first single off of his new album “What a Time To Be in Love.”

Who do we run to? And who do we call? What’s the use in still saying prayers, if deaf ears they fall on. You want to believe there’s a better place when it’s all said and done.

“When you think about artists like Marvin Gaye who spoke about what was going on at that time… and the fact that history repeats itself, ‘ DeVaughn said. “I think this is the most monumental time that we’ve had to be able to fight for change, you know, and change the social climate.”

The key is to keep the faith for our race to be won. It reminds me of a song: What’s goin’ on?. Marvin used to say: ‘Tell me what’s going on.”