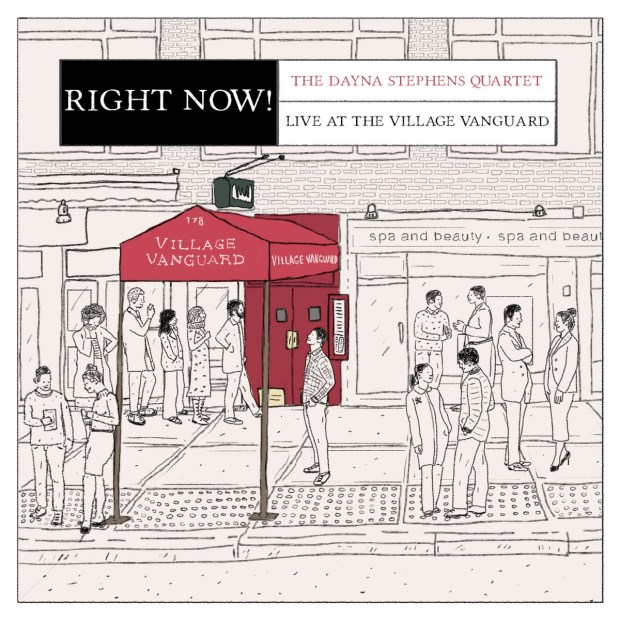

Country musicians dream of playing the Grand Ole Opry. Classical artists imagine themselves on stage at Carnegie Hall. For jazz players, the holy of holies is a far more modest edifice. A narrow subterranean room in the West Village, the Village Vanguard has absorbed sonic vibrations from the music’s greatest improvisers for more than seven decades.

East Bay-raised tenor saxophonist Dayna Stephens made his debut at the venerable club in 2007 with veteran pianist Kenny Barron, and over the years he’s returned several times as a sideman with the NEA Jazz Master. But it was another thing entirely to headline at the Vanguard, performing original music with his all-star quartet. He wrote himself into the vaunted club’s annals last year in a show captured his on recently released 10th album as a leader, ].”

Even without the recording, last year’s performance is an experience emblazoned on his memory, “something I never stop thinking about for more than 10 seconds at a time,” Stephens says from his home in New Jersey. “How many minds have been transformed in that place? I played there for a dozen years, but to lead my own group was another level of nervousness.”

The two-disc album captured his quartet with pianist Aaron Parks, bassist Ben Street, and drummer Greg Hutchinson. Stephen and the his quartet were set to return to the Vanguard (with Jaimeo Brown taking over the drum chair) for two live-streamed shows Oct. 2 and 3 — coinciding with the release of the new album — but the venue just announced it was shutting down for a month to fine-tune is streaming services. Stay tuned for updates on when Stephens’ shows might be rescheduled.

Founded in 1935 by Max Gordon and run by his widow, Lorraine, until her death in 2018 at 95, the Village Vanguard isn’t merely the world’s longest continuously operating jazz venue. The club has attained a singular status by consistently presenting jazz’s most prodigiously creative artists in concerts that have often ended up on era-defining live albums.

Tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins started the ball rolling in 1957 with an epochal trio session for Blue Note, “A Night at the Village Vanguard.” Bill Evans opened up new possibilities for interaction within a piano trio with his classic 1961 Riverside album “Sunday at the Village Vanguard,” a date with bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian that eventually yielded enough music for a three-disc box set (Motian went on to record several sublime albums of his own at the club decades later, but two weeks after the Evans date the 25-year-old LaFaro died in a car crash).

Tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins started the ball rolling in 1957 with an epochal trio session for Blue Note, “A Night at the Village Vanguard.” Bill Evans opened up new possibilities for interaction within a piano trio with his classic 1961 Riverside album “Sunday at the Village Vanguard,” a date with bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian that eventually yielded enough music for a three-disc box set (Motian went on to record several sublime albums of his own at the club decades later, but two weeks after the Evans date the 25-year-old LaFaro died in a car crash).

Saxophonists John Coltrane, Art Pepper and Dexter Gordon all recorded treasured albums at the Vanguard. Vocalist Mary Stallings had been a star on the Bay Area scene for decades when her 2001 MaxJazz album “Live at the Village Vanguard” prompted the New York Times to describe her as “perhaps the best jazz singer singing today.” Vanguard albums get noticed.

If Stephens was nervous confronting the club’s legacy the jitters aren’t apparent. With a broad, pillowy tone and a knack for crafting elliptically lyrical lines, he sounds utterly at home on stage, unhurried and eager to see where the music takes the band.

“For me it feels like playing with a singer,” says Street, who’s become something of a house bassist at the Vanguard in the live-streaming era, performing in recent weeks with bands led by Billy Hart, Andrew Cyrille and Joe Lovano.

“Dayna is a very special musician,” Street says. “We feel lucky we get to play with him. He reminds me more of Wayne Shorter, though he’s listened to everybody.”

Growing up in El Cerrito and Oakland, Stephens absorbed an unusually broad palette of influences far beyond the requisite work of Rollins and Coltrane. The Berkeley High graduate also gravitated to cool-toned Lester Young-influenced tenor saxophonist like Stan Getz and Warne Marsh.

“And Lee Konitz was one of my heroes,” he says, referring to the great altoist who died in April from COVID-19 at the age of 92.

Courtesy of Kuumbwa Jazz Center

San Rafael-raised Jaimeo Brown and Dayna Stephens started playing together as teenagers.

Stephens’ canceled Vanguard shows scuttled his chance to perform with one of his oldest musical relationships. He and San Rafael-raised Jaimeo Brown started playing together as teenagers, sitting in at long shuttered jazz spots like North Oakland’s Bird Kage and Jack London Square’s First Stop.

“From the first moment that we met each other we knew we had a lot of things in common,” says Brown, who’s recorded a series of revelatory projects drawing on spirituals and gospel songs associated with the Gee’s Bend quilters near Selma, Alabama.

With vast technologic and pandemic-driven disruptions in the music business Brown is considering the best platforms to release his third album of spiritually infused jazz. His mid-career perspective on collaborating with Stephens is deeply informed by his first-hand knowledge of the radically constricted path that leads down the Vanguard steps.

“There are very few who figure out how to survive as musicians in New York, and even fewer who are able to play at the Vanguard,” he says. “It’s a huge honor to be there with such a close brother. It’s a blessing.”