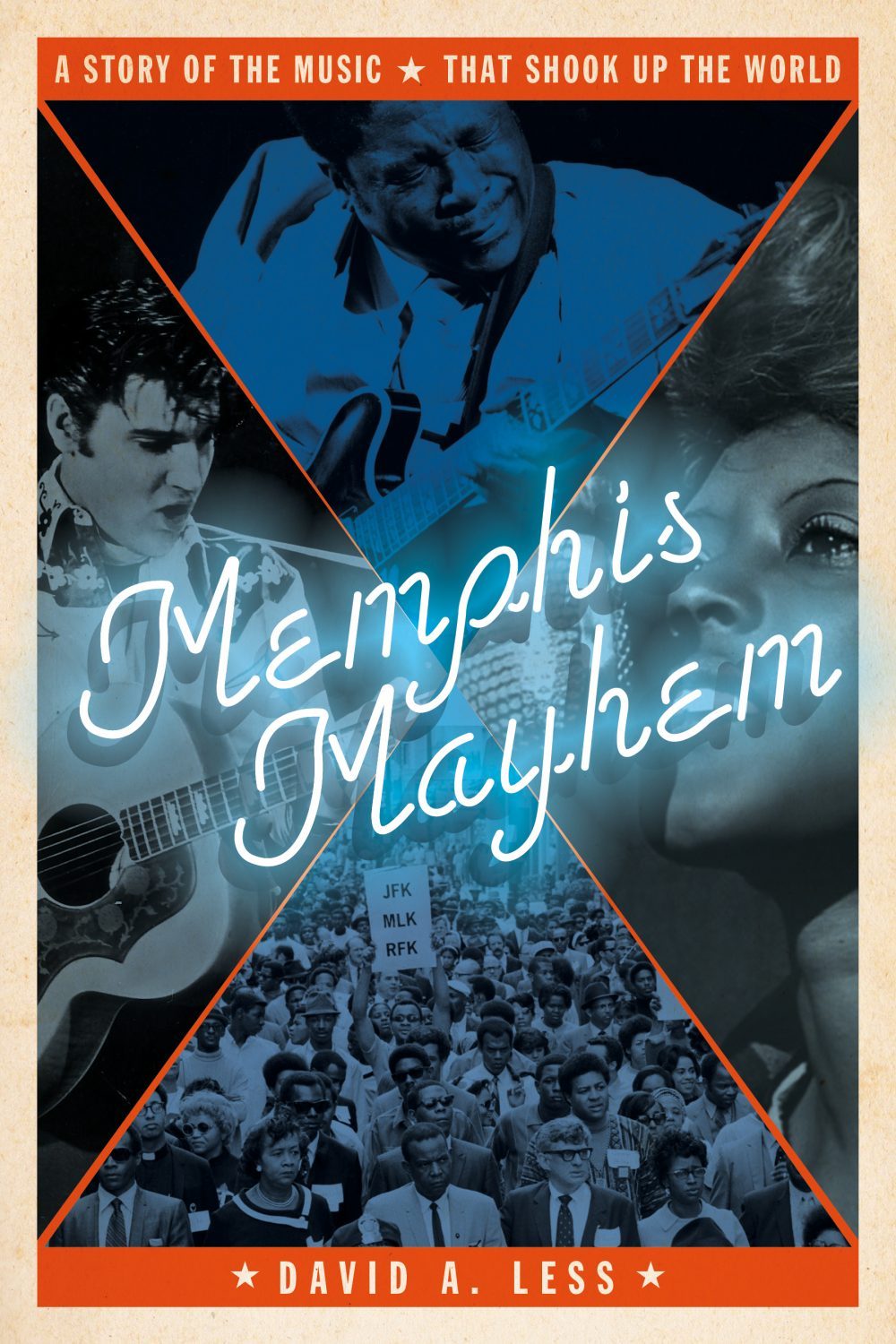

A new book will explore the racial collision that led to a cultural, sociological and musical revolution in Memphis, Tenn. “Memphis Mayhem,” due out Oct. 6, traces the city’s evolution as a mecca for musicians, starting with early blues at the top of the 20th century to the integrated collectives that were Stax acts like Booker T. and the MG’s and on through punk, pop and hip-hop.

Author David A. Less devotes a chapter to successive deaths of budding star Otis Redding, in a plane crash in December 1967, and Martin Luther King, Jr., who was assassinated outside a Memphis hotel in April 1968. Read an exclusive excerpt below:

The year 1962 was a momentous one for Steve Cropper and Stax Records. When Chips Moman quit, Steve was promoted to one of the principal producers. After the success of “Green Onions,” Booker T. & the M.G.s became the house band playing on most of the records through the remainder of the decade.

Perhaps the most important incident that year was when a young African American singer, who had served as a driver for another act, convinced Cropper to listen to his song. The song was “These Arms of Mine” and the singer was Otis Redding, who became Stax’s biggest star until his death in 1967.

During that remarkable five-year period, Redding wrote and recorded a trove of soul classics. He recorded live albums at the Whiskey a Go-Go in Los Angeles and in Europe. Redding was introduced to a younger white crowd at the Monterey Music Festival where he stole the show. The Grateful Dead’s rhythm guitarist Bob Weir said Redding’s performance at Monterey was like seeing God on stage.1

Recording sessions in Memphis are often collaborative efforts between musicians, singers, and producers. Songs take shape during the course of running through the chords, and arrangements can be malleable usually depending on the particular producer and rhythm section. At Stax, the music often developed while the tape was running/

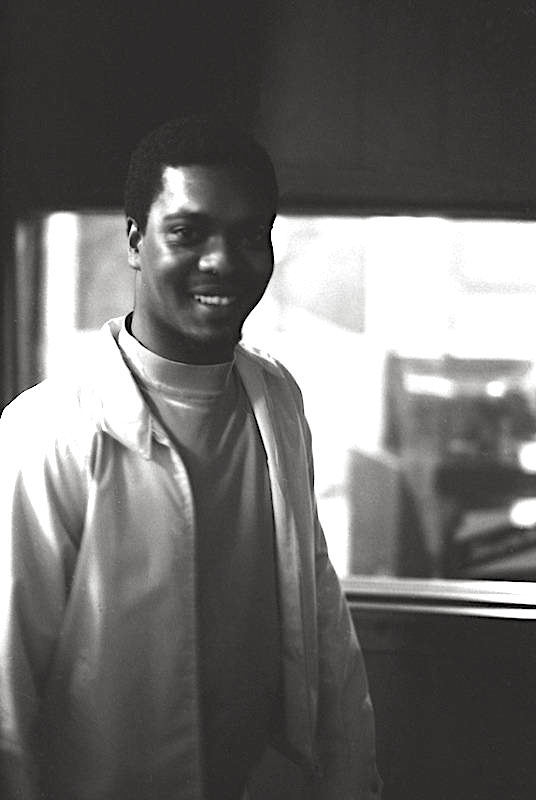

Booker T, courtesy of Terry Manning Courtesy of Terry Manning

Duck Dunn described a typical session and how Otis Redding changed things: “It was a complete collaboration. Booker or Isaac or somebody could give me a line to play. And if I strayed from it, and it helped it, they didn’t force you to do that. It was just—they gave you your space.

“When [Otis Redding] did ‘Respect’—and I never will forget—most of Stax’s stuff was done with a lot of whole notes and half notes and stops with the horn section. When he did ‘Respect,’ and he started that intro, da-da-da da-da-daa. They looked at him. They never heard anything like that before. I said, ‘Jesus.’ I didn’t believe it was going to work. Man, it came off. He was just a joy and he always smiled.”

Otis was bringing Stax soul music to a much bigger audience when he was killed in an airplane crash along with label mates the Bar-Kays outside Madison, Wisconsin, in December 1967. It was a tragedy that set Stax on its heels. The Bar-Kays, recent high school graduates, had recorded a hit titled “Soul Finger” and had been touring as Redding’s backup band. They were just kids, most fresh out of high school. The Bar-Kays had performed in Cleveland, Ohio, on Saturday, December 9, backing Otis Redding on a short weekend run of shows. The private airplane left the next day around noon for that night’s show in Madison, Wisconsin.

Their routine was for two members to stay behind and return the rental vehicles, catching a commercial flight to the next engagement. That afternoon, bassist James Alexander and guest vocalist Carl Sims stayed behind. With no available flights to Madison, they flew to Milwaukee where the pilot was to pick them up after dropping off the band.

Trumpeter Ben Cauley sat behind Redding who was in the copilot’s seat. Phalon Jones sat across from him. It was cold and foggy in Madison, and upon the descent, the airplane crashed into Lake Monona. Cauley was the only survivor of the crash and the only one on board who could not swim.

“I was cold, I was shaking,” Ben told me. “Then, for a while, nobody was there. They had floated away or drowned. And I felt like I knew I was next. I saw Ronnie [Caldwell] come out. Ronnie came up and he was hollering for help. And I was saying, ‘Ronnie, hold on, man. I’m trying to get over to you.’

“I had this airplane seat, man. I was trying to get to him, and the more I tried to get to him, it was slipping out my hand. And finally it slipped out of my hand, and at that point, I said, ‘Oh, no.’ I knew I was next because I didn’t have one, and another one came straight to me.”

By this time, rescue boats arrived and pulled Cauley out of the lake, and he was told to lie down as others were retrieved from the waters.

Alexander and Simms waited at the airport in Milwaukee for the pilot. When they heard about the accident, they were picked up and driven to Madison. “I was numb,” Alexander remembered. “First of all, I was seventeen years old. I had never had any kind of experience like that. But I guess the moment of truth came after they brought us from Milwaukee to Madison, Wisconsin. The authorities came and got us and the first thing that we had to do is go to the morgue and identify people.

“Just a strange thing to do, especially when all these guys in the group were your friends and you grew up with them and stuff like that, and then here you have to go and identify them in a morgue. That’s tough.”

Stax publicist Deanie Parker, a bright powerhouse in a key role at the label, recalled the days following the accident: “I think that I remember our wondering where do we go from here, because clearly at that time Otis was destined to be the biggest artist. Most important, Otis was a wonderful human being. He was a little bit shy, soft-spoken, fun, genuine. But not only that, we had another group of very, very talented young men who were studying the musicians’ every move.

“It was an incredible loss. What we experienced in that place that night when we first heard it. I don’t think that any of us who are still living have forgotten where we were at the time we heard the plane had gone down in Lake Monona.

“For days after that, it was horrible. There was a funeral every day it seemed. The search was going on. It was the dead of winter. I think probably the worst experience that I had after it was all over, they delivered those trunks from that plane that had their clothes and things in them. Water was still dripping out of them into the studio. It was just miserable.”

Then on April 4, 1968, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel where many Stax artists stayed while in town. It was a turbulent time for Memphis and the nation. The city leaders were rightfully concerned about the reaction of the African American citizens. Stax artist Isaac Hayes was asked to serve as a spokesperson to bring calm to the city.

Deanie Parker continued, “Apparently, people in high places, especially in the political arena, really didn’t think very much of what we were doing until they needed someone they thought could appeal to the people who they thought were going to burn this city down. Then Isaac Hayes and Stax Records became very important. That says something about this city and what was going on at that time. Until that time, they probably would not have even wanted anybody to know that we existed. They certainly didn’t approve of what was going on at Stax because everything we were doing was very evil.”

Change was in the air for Memphis music. In 1968, after the assassination of Dr. King, Stax’s longtime distribution agreement with Atlantic Records ended. Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun had sold their company, Atlantic Records, to Warner Bros. in 1967. The sale triggered a proviso in Stax’s distribution agreement: if Wexler was not involved, the contract would terminate. The problem was, according to the Stax contract, Atlantic now owned all of the master recordings it had been distributing. This meant no catalog sales for Stax the year after their best-selling artist died.

Catalog sales are the lifeblood of record companies. They provide cash flow from product that typically has no costs beside distribution, manufacturing, and licensing. The production and marketing expenses were often already recouped during the initial sales period. Artist royalties were usually advanced against sales when the master tapes were accepted, and often the advance was not recouped. This meant that no payments were due to the artist until the record had sold large numbers.

Larger retail outlets often had generous billing periods, sometimes resulting in a full quarter or more before the labels collected on new hit records. Catalog sales were ongoing, and although the billing periods were still stretched out, the longevity of sales gave record labels a steady stream of operating cash while searching for their next hit. The loss of Stax’s catalog was potentially devastating to the company.

Al Bell joined Stax as a radio promotions specialist in 1965. The company was riding a crest of hit records, including Otis Redding’s, and wanted assurances that black radio stations would play their records. An African American former disc jockey, Bell rose through the ranks of the company, serving as vice president and later as co-owner with Jim Stewart and eventually as the sole owner.

Stax was now a fully integrated company from musicians and producers to owners. But they were also a record label with no catalog. Bell oversaw an ambitious effort to release enough product to quickly rebuild. The idea was to get records into the marketplace and build a new catalog.

In late 1968, Stax was sold to Gulf & Western, a large conglomerate looking to diversify its holdings. Estelle Axton left the company in 1969, and Al Bell was promoted to vice president. He knew it was critical for Stax to have more hit records if it was going to survive. During an eight-month period, Bell supervised the release of twenty-seven albums and thirty singles in his plan to restock the catalog. Gulf & Western held the company until 1970, when Jim Stewart and Al Bell bought back the label.

By 1970, both Stax Records and Hi Records, stalwarts of Memphis soul, had African Americans included in ownership, with Willie Mitchell and Al Bell influential in signing artists and shaping the direction of their labels.

Excerpted from “Memphis Mayhem: A Story of the Music that Shook Up the World” by David A. Less. © by David A. Less. Published by ECW Press Ltd. Available from Amazon, your local independent bookseller, and wherever books are sold on October 6.

ECW Press