Advertisement

100 years ago, Mamie Smith recorded a seminal blues hit that gave voice to outrage at violence against Black Americans.

By David Hajdu

Mr. Hajdu is a cultural historian and music critic.

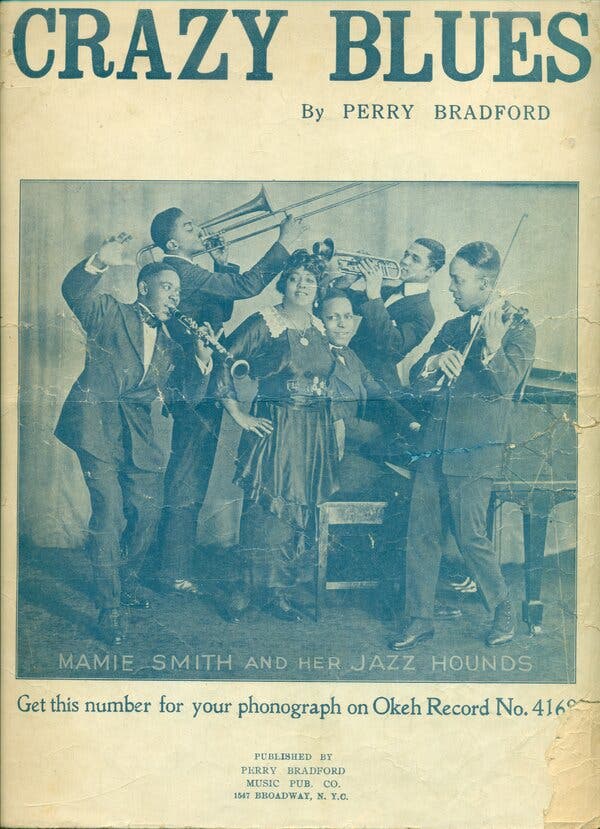

On Aug. 10, 1920, two African-American musicians, Mamie Smith and Perry Bradford, went into a New York studio and changed the course of music history. Ms. Smith, then a modestly successful singer from Cincinnati who had made only one other record, a sultry ballad that fizzled in the marketplace, recorded a new song by Mr. Bradford called “Crazy Blues.” A boisterous cry of outrage by a woman driven mad by mistreatment, the song spoke with urgency and fire to Black listeners across the country who had been ravaged by the abuses of race-hate groups, the police and military forces in the preceding year — the notorious “Red Summer” of 1919.

“Crazy Blues” became a hit record of unmatched proportions and profound impact. Within a month of its release, it sold some 75,000 copies and would be reported to sell more than two million over time. It established the blues as a popular art and prepared the way for a century of Black expression in the fiery core of American music.

As a record, something made for private listening in the home, “Crazy Blues” was able to say things rarely heard in public performances. Seemingly a song about a woman whose man has left her, it reveals itself, on close listening, to be a song about a woman moved to kill her abusive partner. As a work of blues, it used the language of domestic strife to tell a story of violence and subjugation that Black Americans also knew outside the home, in a world of white oppression. The blues worked on multiple levels simultaneously and partly in code, with “my man” or “the man” translatable as “the white man” or “white people.”

Ms. Smith, a skilled contralto with a keen sense of drama, brought clarity and panache to words that would strike today’s listeners as conventional only because they have been replicated and emulated in countless variations over the past century: “I can’t sleep at night/ I can’t eat a bite/ ’Cause the man I love/ he don’t treat me right.”

Out of her mind with despair, the singer turns to violence against her oppressor for relief in the chorus that gives the song its title: “Now the doctor’s gonna do all that he can/ But what you’re gonna need is an undertaker man/ I ain’t had nothin’ but bad news/ Now I’ve got the crazy blues.”

That a woman was singing made the song an acutely potent message of protest against the forces of authority, be they male or white, domestic or sociopolitical.

With “Crazy Blues,” Mamie Smith opened the door to a surge of powerfully voiced female singers who defied the conventions of singerly gentility to make the blues a popular phenomenon in the 1920s. Indeed, the blues became a full-blown craze, with listeners of every color able to buy and listen at home to music marketed as “race records.” The form was initially associated almost exclusively with women such as Ms. Smith, Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters and Bessie Smith. They and many more women made hundreds of records that sold millions of copies over more than a decade — well before the great bluesman Robert Johnson stepped into a recording studio for the first time, in November 1936.

There had been some blues recordings before “Crazy Blues,” nearly all instrumentals or records, often made by white musicians, of songs of various kinds with the word “Blues” in the title. A feeling of veracity as Black expression was part of the secret of “Crazy Blues.” But so was the song’s disturbing but powerful ending, in which Ms. Smith sings allegorically of the darkening circumstances: “There’s a change in the ocean/ change in the deep blue sea.” In the concluding verse, she speaks of changing the way she responds. She has decided to “go and get some hop,” she announces, and “get myself a gun and shoot myself a cop.”

It was an idea at once abhorrent and cathartic. Recorded in the wake of horrific violence against African-Americans, “Crazy Blues” was not only an outlet for exasperation in the face of “nothin’ but bad news.” It was also a rallying cry in Black musical language and a call for redress through reciprocal violence — one that broke daringly out of domestic allegory into a literal sphere where the police and the military claimed the only prerogative to shoot at will.

One hundred years later, the blues endures as the essence of American music, from rock ’n’ roll and three-chord country songs to hip-hop and contemporary R&B. If in a 2020 hit like Chris Brown and Young Thug’s “Go Crazy,” the title means to party, not to feel blue, we should remember that Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” was also a dance tune: People were not only moved by it; they moved to it.

From its earliest days, the blues has always done many and sometimes contradictory things at the same time, as both an outlet for rage and a release from it. Hatred and violence have hardly disappeared from the American landscape, but neither has the blues.

David Hajdu (@davidhajdu) is the music critic for The Nation, a professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and the author of the forthcoming “Adrianne Geffel: A Fiction.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.