At 9 years old, jazz bassist Christian McBride knew he wanted to make music for the rest of his life. His mother bought his first instrument, an electric bass, and he “took to it like fish to water” in his West Philadelphia home.

Since then, McBride, 47, has become one of jazz’s most important artists. He’s won six Grammy Awards and has worked with the likes of the Roots, Chaka Khan, Natalie Cole, and most memorably, the Godfather of Soul: James Brown. Right now, he’s the co-artistic director of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, along with Jonathan Batiste.

Related stories

McBride has spoken out for decades against racism in the performing arts. (He was part of former President Bill Clinton’s 1997 town hall meeting on the topic.)

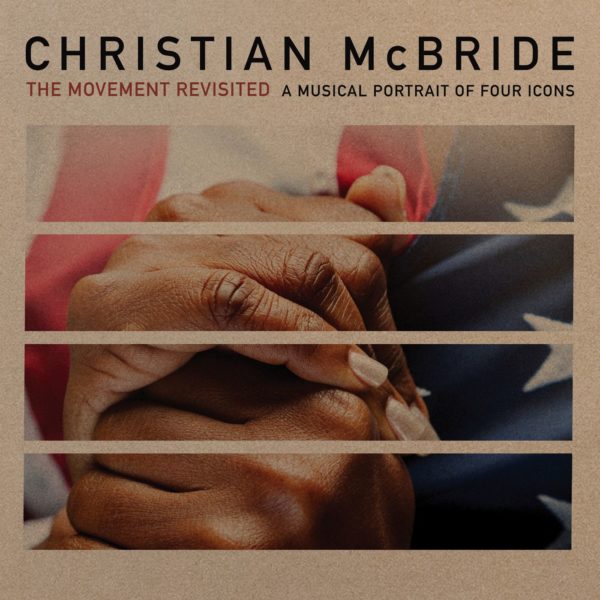

In recognition of Black History Month, McBride recently released The Movement, Revisited: A Musical Portrait of Four Icons. The album highlights critical speeches from the civil rights era by Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“I decided to choose four people who meant something to, not only our culture, but to me,” McBride said. The speeches are voiced by Philly’s Sonia Sanchez, along with Vondie Curtis-Hall and Dion Graham, over jazz numbers composed by McBride.

McBride talked with The Inquirer about the album, his inspirations, and the authenticity of his music.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

There’s always a need to know what happened in your past. We somehow tend to think that we’re making progress when what we’re really doing is picking up the ball where someone left off. So a lot of what we’re fighting for in today’s culture are old battles.

It’s wonderful to dream of a utopian world where human rights and equality won’t have to be fought for, but the reality is that we’re flawed as human beings. There’s always going to have to be a reminder, a little tap on the shoulder to say, ‘Hey, remember what we’ve been through.’

I think I do that without even trying. I think there’s a certain pulse, there’s a feel, there’s a rhythm, and there’s a tone that’s unmistakably black. And I think that most black musicians have that without even trying.

So many people. Particularly, with a project like this, when you think of long-form jazz pieces, the first name that comes to mind is Duke Ellington. No one did it better than him when it came to long, extended works. He was our first great composer.

But then there are also people like Wayne Shorter and Quincy Jones — who I feel people don’t quite realize that long before Quincy met Michael Jackson, he was a legend as a big band writer and arranger. When it comes to learning how to write for jazz ensembles, particularly big band ensembles, Quincy Jones has always been one of my go-to’s.

I tried to be as specific as possible with the title: The Movement Revisited: A Musical Portrait of Four Icons. Hopefully, the album will conjure up some really strong feelings for the people who were there and who lived through that era.

And for the people who don’t know much about the era, particularly young people, I hope it inspires them to go do their homework.

I firmly believe that people can always tell when you’re honest, when you’re true, and when you’re faking it and phoning it in. Even the untrained ear can tell. You don’t have to be a jazz lover to listen or watch a musician play and tell when they’re feeling it or not.

I like to think that every time I have my bass in my hand, I’m 100% feeling it, and think people know that.