He had it all but he didn’t know it. The limos, the five-star hotels, the red carpets, the adulation of auditorium audiences. Nathan Cavaleri had made it in America.

He was a guitar hero; supernatural, untouchable.

There were the appearances on Good Morning America, Conan O’Brien, Arsenio Hall.

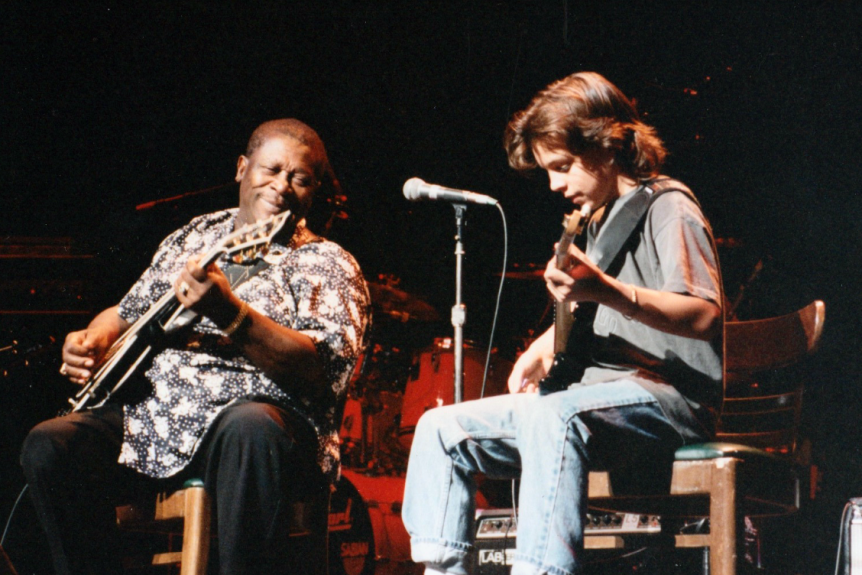

There was the touring with B.B. King, perhaps the most influential blues musician of all time; performing alongside Bonnie Raitt and Etta James in front of president Bill Clinton; playing after Elton John and before Jimmy Page and Robert Plant for 60,000 people in Zurich; making albums for Michael Jackson’s record label.

“For three years it just exploded,” his former manager Russell Hayward says.

But Nathan Cavaleri was not able to indulge in the usual rock star excesses. He was a child.

Instead of afterparties, he had to do his homework. He was barely aware of the stratosphere he was moving in. “I had no idea of the magnitude of those experiences and who I was playing with,” he says now.

And he was a sick child when it all took off, battling leukaemia.

There would be a reckoning. No child star escapes unscathed, let alone one playing for his life.

Ten years after the music stopped Cavaleri would suffer, long and hard; down, down through the nine circles of hell.

All the passion gone, the mojo departed, paralysed with fear, he would reject the adorable child prodigy that he had been.

Five agonising years later he would emerge recreated; bruised, changed, stripped bare, altered, but finally fully himself and singing his own song. He says now he’s “at peace” with “whatever happens on this journey”.

Everything that has happened has brought him to this place. “I can really hear it in the music,” says musician and long-time friend Mark Lizotte, aka, Diesel.

Fellow musician Ash Grunwald believes Cavaleri’s music is all the better for it. “As a songwriter, all of this stuff is gold,” Grunwald says.

“If you feel strongly about anything, it really helps your songwriting. And there’s a lot of stuff to be mined there.”

‘Guitar prodigy’ makes me cringe

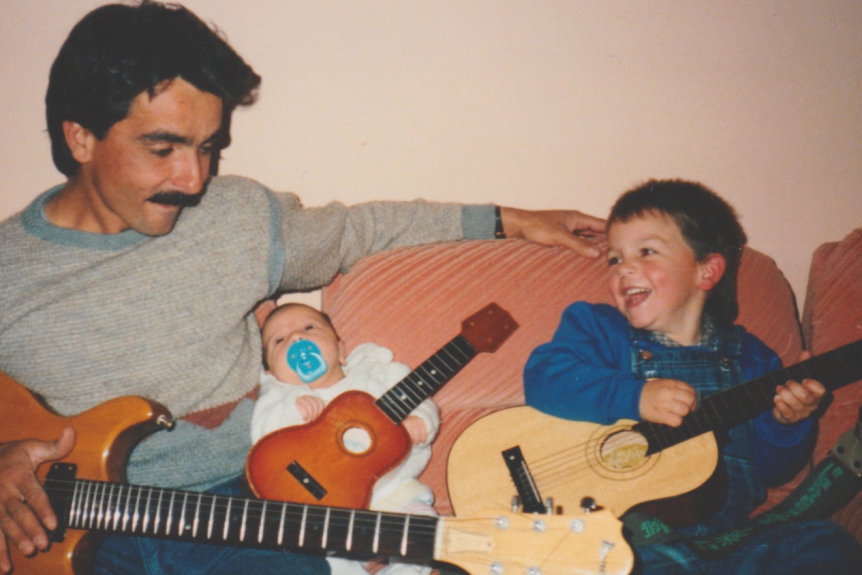

From the age of three Cavaleri had copied the guitar playing of his father Frank, a bricklayer who played the blues constantly at home.

“When he started getting my ideas and twisting them around, I said to my wife Jo, ‘this kid is really scary’,” Frank admits.

At six, Cavaleri was diagnosed with leukaemia.

“That’s probably when my relationship with the guitar deepened because it took my mind away from having to deal with those medical procedures and all that pain,” Cavaleri says. “It was one of the very few things that brought light.”

All the pain was poured into the guitar. “Sometimes it was anger, a lot of the times it was sadness.”

When he was seven, the Starlight Foundation found a way to grant a very sick boy an almost impossible wish — to jam with his ultimate guitar hero Mark Knopfler from Dire Straits.

“All of a sudden I’ve got this fire to get up and deal with the lumbar punctures or whatever it was. My attitude changed. I had to practise and practise and practise.”

Years later he would realise the Fernandes guitar Knopfler gave him that day was the uniquely personal one he had used for the Love Over Gold album.

“That guitar became my best friend. And when I went to bed, I’m thinking about playing that guitar and when I wake up I’m playing that guitar,” Cavaleri says.

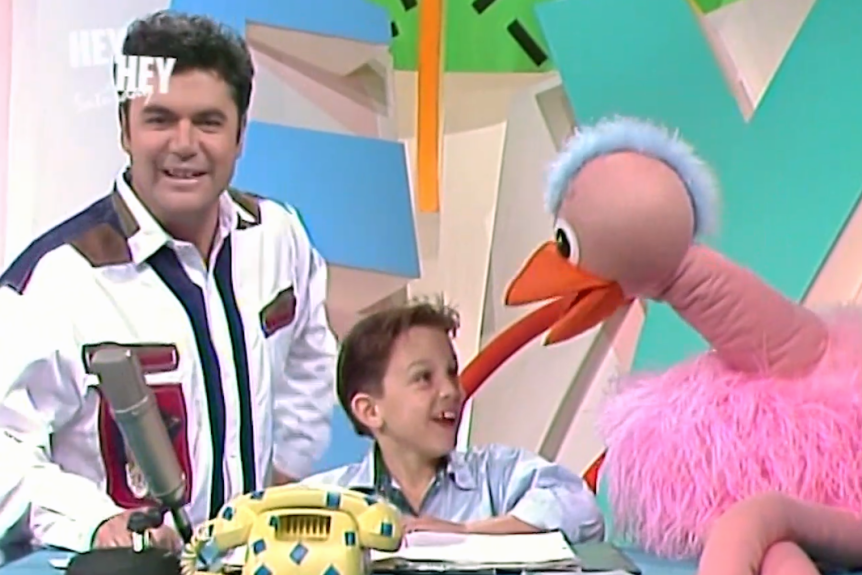

When Cavaleri returned from London, everything changed. The amiable cute kid, the freakishly gifted child was in demand. A regular on Hey Hey It’s Saturday, the Midday Show, a darling of the print media.

“It brought so much joy to my life to play on those TV shows,” he says now.

But to this day: “Those two words — guitar prodigy — still makes me cringe.”

Jimmy Barnes and his wife Jane offered him a record deal. That came with a tour playing to thousands of people a night with Jimmy and Diesel. “I just remember being amazed at what I was hearing,” Diesel says. “It just sounded like a fully blown blues master up there.”

Diesel recalls that Cavaleri sometimes looked pale and ill. He was being treated for leukaemia, but Cavaleri says, “As soon as I’d step onto that stage, it was like I’d have superpowers because everything would just disappear.”

By then, Cavaleri was only nine years old. But he already understood the suffering that the blues comes from and he played with his whole heart.

“Nathan had this spiritual connection, I think,” former manager Russell Hayward says. “Taking control of his mind when he was playing.”

They started with playing small blues clubs in the US and did a segment for CNN that was repeated on an hourly loop. Michael Jackson saw it and got on the phone.

“I didn’t really get what a big deal it was to be signed to Michael Jackson’s MJJ label or even to perform with him,” Cavaleri says.

“I just didn’t understand it until years later.”

Allegations of child abuse against the singer also emerged later but Cavaleri only had positive interactions with him.

“Not once did my over-protective parents have any doubts in our experience with him,” he says.

Hayward had been warned about predators in the industry and Cavaleri was never left alone. His whole family including his younger brother Josh travelled with him.

“Because we nearly lost Nathan it was so important for us to stay together,” his mother Joanne says.

Cavaleri says despite his growing fame, his family kept him grounded.

“My parents didn’t give me any special treatment or anything like that,” he says.

“They disciplined me like every other kid. I had tutors, we had homework. Respect, love, family unity, all those things.”

Cavaleri made a McDonalds commercial with B.B King, appeared on Baywatch and made a children’s film Camp Nowhere where he shared a kiss with Jessica Alba.

And then he went from all that, back to school in suburban Sydney where the culture shock was brutal.

Teachers thought he had already had enough attention, other students bullied and derided him.

“One of the most challenging parts of my childhood was going from onstage and feeling that celebration, to then going back to the classroom where it was like I had a target on me,” Cavaleri says.

“I definitely had some major troubles with my self-esteem throughout high school because I just couldn’t relate to a lot of the other kids.”

Teen Cavaleri felt ‘cheesy’ playing blues

When Cavaleri was 12, the leukaemia, the illness that had indirectly brought him fame, had gone into remission. In the years that followed, so too did the passion for performing.

By 15 he started feeling embarrassed about his accomplishments and refused to play guitar.

“Having that type of attention as a kid has both inspired and haunted me,” he says.

“I wouldn’t play it at school, I probably lost heart, lost my connection with the guitar because there was just a lot of shame around it.”

Grunge was the music now and he thought people would think he was “cheesy” for playing the blues.

That boy wonder had been, says Hayward, “a sideshow, a pantomime show” now he wanted to be “normal”, just like everyone else.

But if he wasn’t Nathan Cavaleri, famously dazzling guitarist, then who was he?

His last live gig of that time was the 2000 Summer Paralympics, then he picked up a shovel and went to work as a brickies’ labourer for his father.

“I was in soul-searching mode.”

Chronic insomnia, anxiety plagued career

On his own time, he was honing his skills as a producer.

He was mixing an album in Melbourne when a friend brought a woman named Amy O’Brien into the studio. “I remember seeing a face with a beautiful smile, just radiating eyes and I just had to hang out with her. She just had this magnetic energy.”

She was 19 and he was 23. A year later she moved to Sydney and they married.

“He never spoke about himself or his past performances or who he played with or anything like that,” Amy says.

But as much as he tried to outrun it, the past was waiting to get him. It came rushing to take him down, to consume him. The reckoning was here.

He had put together a hard rock band, Nat Cole and the Kings, but was so “insecure” that he didn’t use his own name. The band was doing well until he walked onto the stage at the Queenscliff Music Festival one night.

“I had pins and needles all through my body,” Cavaleri says.

“I had a mini blackout. That was my first anxiety attack but I didn’t know it was an anxiety attack.”

He had recently lost friends from cancer and suicide.

“I remember thinking ‘this could happen to me, it could happen to me tomorrow’,” he says.

“I would go to bed thinking of death, I would wake up thinking of death. And that went on for years.”

The trauma he hadn’t understood as a child hit him now. That he had been close to losing his life, that he hadn’t come to terms with being a child star growing up on the road.

The daily anxiety, the fear and chronic insomnia would go on for five years, eating him up, paralysing, terrifying.

“Anxiety was claiming all these areas of my life, until it ended up corrupting the one place where I thought I was untouchable, which was the stage,” Cavaleri says.

“The stage went from something that brought me refuge and so much joy to just terror.”

Cavaleri decided to confront his past. He started writing about his experiences and it was a real eye opener. He realised he had got it all wrong. No one was laughing behind his back for being cheesy.

People admired him. There should be pride, not shame, a celebration of a remarkable life.

He suddenly understood that, “People work their whole lives to get the name that I have,” he says.

“I had thought the world was trying to crush me but really it was trying to wake me up. And when it did it was better than it ever was before.”

Loading…

His friend and former band member Kenny Jewell had a solo gig and invited Nathan to join him. But first Cavaleri had to learn how to overcome the fight or fright response to performing.

“Then I got up on stage and it was electric,” Cavaleri says.

“It felt like I’d gone to heaven and back. Just power and fire and excitement again.

“It reminded me of how I used to play when I was a kid.”

Now he brings his fears onstage. They are part of his narrative, of how he has been shaped, they are in the show and in his new album Demons.

“I was able to channel all that into the music. And by doing it under my name meant no more hiding.

“It’s kind of like I’m stripped of all my clothes and I’m out there. I’m just me. And I’m Nathan Cavaleri.”

Loading…

Watch Australian Story’s return episode, Growing Pains, on iview.