Thom Bell is on the phone from Washington state, talking about Philly soul.

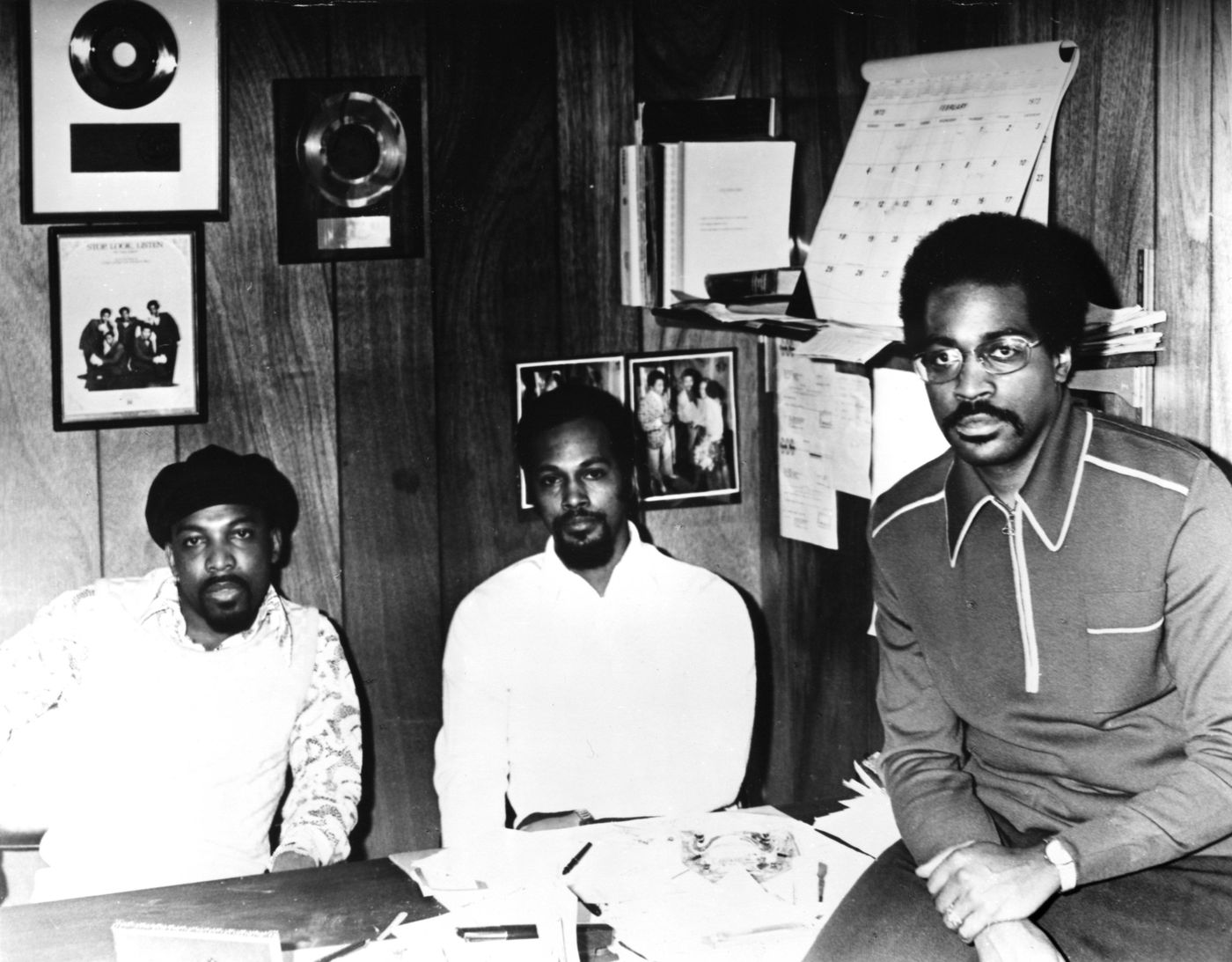

The producer, arranger, and songwriter stands alongside Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff — “The Mighty Three” — as one of the titans who created the Sound of Philadelphia that defined sophisticated R&B in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

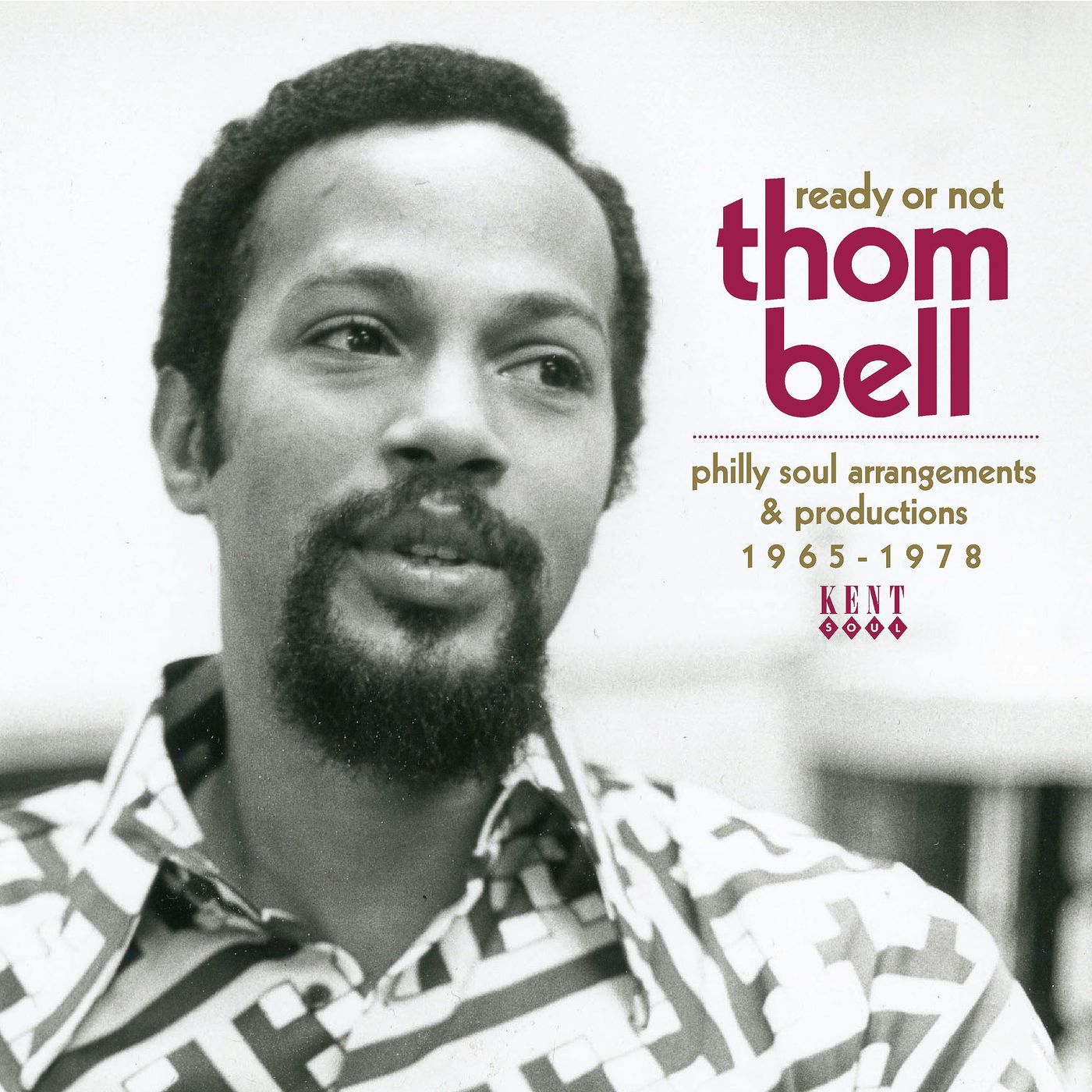

Now he is the subject of a new compilation album that tracks the height of his career. Ready or Not: Philly Soul Arrangements & Productions, 1965-1978, on the Ace Records label, is a 23-song set expertly compiled by Bob Stanley, the music historian who’s also a member of the British dance-pop band Saint Etienne.

The collection — which takes its title from “Ready or Not (Can’t Hide From Love),” the 1968 Delfonics song that was revived by Lauryn Hill of the Fugees in 1996 — includes plenty of indelible Bell hits, like the Stylistics’ “You Make Me Feel Brand New” and Spinners’ “Could It Be I’m Falling in Love,” while digging deep for Lesley Gore’s “Look the Other Way” and Ronnie Dyson’s “One Man Band (Plays All Alone).”

All are marked by the lustrous, lighter-than-air delicacy and a refusal to be weighed down by pop music convention that is a Thom Bell trademark.

“I don’t write anything that’s hard on the ear,” says the 77-year-old Grammy lifetime achievement winner and Songwriting Hall of Fame inductee, in a rare interview from his home near the Canadian border, where he moved in the late 1970s and lives with his wife and five dogs.

“I don’t care if it’s loud, big-bam-boom James Brown, or anything else. It has to be pleasing to the ear.”

To say that Thom Bell’s songs meet that prerequisite would be an understatement. “Betcha By Golly, Wow,” they surely do.

Bell wrote that song with his musical partner, Linda Creed. “We rode the ethers of life and music together.” She wrote “You Make Me Feel Brand New” for him. She died at 37 in 1986, and he chokes up talking about her. “Her husband and I were the last two people to throw dirt on her grave.”

“Betcha” was originally recorded by Connie Stevens in 1971 as “Keep Growing Strong” before becoming a hit for the Stylistics the next year, and later was covered by Prince.

Bell was born in Jamaica and grew up in West Philadelphia with nine brothers and sisters. His mother was a pianist and his father played accordion and Hawaiian lap steel guitar. Young Tommy got his first drum kit at 4, and studied classical piano. There was not a radio in the house.

Then his father opened a restaurant, and he heard Little Anthony & the Imperials “Goin’ Out Of My Head” on the radio. The work of two Bell favorites — writer Teddy Randazzo and arranger Don Costa — “was the music I was hearing in my mind.”

He gave up on classical to make his own pop music. “She supported me,” he says of his mother, who died earlier this year at 99. He played her favorite song, Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say,” on piano for her on her deathbed.

Bell and Gamble met when Gamble walked Bell’s sister home and Bell was playing piano in the living room. Soon they were together in a group called Kenny & the Romeos, playing regularly at clubs like Loretta’s Hi-Hat in Camden County. When Bell left, he was replaced on piano by Huff.

The list of Philly soul hits that Bell was instrumental in creating is long. He wrote “I Can’t Take It,” by the Orlons, with Gamble in 1965 when they were hustling African American musicians trying to break in at the dominant, white-owned Cameo Parkway label.

In 1968, he penned “La-La (Means I Love You),” with William Hart of the Delfonics, though he says credit should also go to Hart’s toddler son, who heard the melody and starting singing gibberish that turned into the title.

Ready or Not also includes “Back Stabbers,” the 1972 breakthrough hit for the O’Jays on Gamble and Huff’s Philadelphia International Records label, for which Bell did the string arrangement.

Stanley praises TSOP’s architects for their “aspirational” sound. “If you wanted to put Philadelphia on the map, you couldn’t do better than call your label Philadelphia International,” says Stanley, who was smitten with Bell’s songs in London in the ’70s. “It was, ‘We’re here, and we’re going to reach out to the whole world and tell them what we’re doing.’ ”

As an arranger, Stanley compares Bell to Ennio Morricone, the revered Italian film composer who died last week.

“The instruments he uses are very unusual,” says Stanley, speaking from Yorkshire in England. “On ‘Didn’t I (Blow Your Mind This Time),’ he has an Alpine horn followed by a sitar. That’s insane! … Quite often he played all the instruments himself, so the label couldn’t complain about the cost. It all comes from his own imagination. He’s closer to a soundtrack composer than a regular pop music arranger.”

“I’m a very independent guy,” Bell says. “I’m not a follower. I’m a leader, and the person I want to lead is me.” He repeats a personal motto: “You never can tell when you’re with the Bell.”

In the early 1970s, Atlantic Records asked him to produce Aretha Franklin, at the peak of her popularity. He turned the job down. “She didn’t need me,” he recalls.

Instead, he chose to work with a journeyman group from Detroit: the Spinners. He told them he would buy them each a car if he failed to get a No. 1 R&B hit. If he did, he was owed a custom Cadillac. “I’ll Be Around” was their first of five chart toppers.

Bell co-owned the 309 S. Broad St. building that housed Philadelphia International (and Cameo-Parkway before that) with Gamble and Huff, before it was demolished in 2015.

He named the “Mighty Three” publishing company, and designed an insignia with a trio of elephants. “Because they are world’s largest mammal on land, and you can never forget our tunes.”

But he resisted several offers to become a partner in Philadelphia International, choosing to retain the freedom to work on other projects with non-PIR artists.

So despite Bell’s prodigious resume — including collaborations with Elton John, Teddy Pendergrass, Deniece Williams, and Johnny Mathis, who he says is the best singer he worked with — his name is not as recognizable as the Gamble and Huff brand.

Ready or Not aims to bring more attention to his body of work. But if only those in the know are aware of his accomplishments, that’s OK by Bell.

“Nobody did that to me,” he says of being an unsung hero. “I did that to myself. I got what I deserved. I got the satisfaction of making music. I got to make a few bucks. And I was able to think and do what I wanted to do. I’m in it for the love of music. That’s what makes my heart beat.”