Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

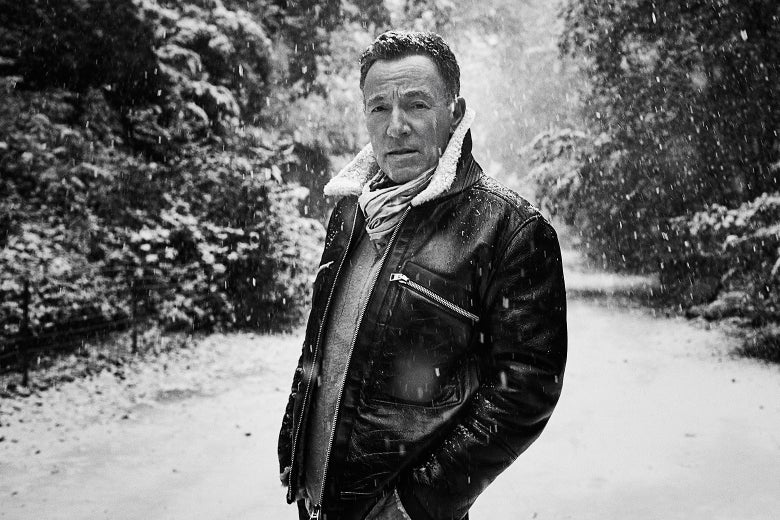

The first question raised by the new Bruce Springsteen album Letter to You is how many Bruce memoirs is too many. In the past half-decade, the now-71-year-old arena-rock master has produced a 500-page autobiography, a Broadway stage show based on the autobiography, and a Netflix performance special based on the Broadway show. And now, in many ways, comes their E Street Band album counterpart, not to mention its accompanying Apple TV+ making-of documentary. If these retrospective exercises are, as the title track loudly implies, Springsteen’s intimate letters to his fans, our mailboxes are getting awfully stuffed. At what point does it all turn into spam?

Thankfully, with Letter to You, I’d say not quite yet. It’s certainly a nostalgic record in its inspiration, which was the death in 2018 of George Theiss, the other surviving member of Springsteen’s teenage rock band, the Castiles—his “first and greatest school of rock,” as he says in one of the documentary’s solemn voice-overs. That eventually led to a 10-day writing binge last year that produced the album’s core set of tracks. Guessing by external evidence, that may be the largest batch of genuinely new material he’s produced in about a decade. Several lyrics call up scenes he’s described before, from those years of playing union halls and beach dances. But more of them assess what it means to be the “Last Man Standing” and surrounded by “Ghosts,” as two of the song titles put it. There’s an atmosphere not just of summing up but of reflecting on the summing up, how that’s altered him, and what comes next, if fate allows. (And given how ridiculously fit he still appears, fate probably will.) This lends Letter to You a kind of meta-memoir layer that staves off part of the risk of redundancy.

But that wouldn’t be enough, considering how many of the songs ride that one train of thought (with all the locomotive metaphors here, it’s definitely a train and not a highway), if Springsteen hadn’t made a few other extremely canny decisions. First, most obviously, on a record that looks back on his life in music, he called together the group of people who carry that legacy in their muscles and bones, the E Street Band. More importantly, he heeded a couple of the members’ advice and restrained himself from working up full demo versions of the songs on his own, as he’s habitually done ever since the band reunited in the late 1990s. That’s tended to lock him into his arrangements and reduce the players to actors following his musical script. Instead, he played them the tunes acoustically in his studio and let them invent their parts spontaneously, in a weeklong recording spree that kind of mirrored his original writing binge. So the album comes directly off the floor, like nothing since a few cuts from Born in the U.S.A. in the mid-1980s.

The method yielded a return to the classic 1970s Born to Run sound—the girl-group/Motown grandeur and the theatrical piano-drum-guitar-sax-organ-glockenspiel dynamics (Clarence Clemons’ nephew Jake fills in for his uncle for the first time on record)—not to mention the group’s permanent destroy-the-room concert energy. It’s something their restless, self-critical leader has seldom been relaxed enough to allow on new records. Now he’s embraced it—in the doc, you hear him shouting joyfully to pianist Roy Bittan to make his part “more E Street, more E Street!”—and it’s pretty glorious. While they all must be punching the walls that they can’t take these anthemic pleasers on the road in pandemic times, much of it comes to listeners as a serendipitous simulation of the roar and the heat we’re missing in the live experience. A track like “Burnin’ Train” conveys more propulsive feeling than any of Springsteen’s mostly overcontrolled albums have managed this century. You can let the album wash over you without fussing about which songs ultimately work or don’t. The arrangements justify themselves.

Of course, there’s a danger there of pandering to fans’ own nostalgic wishes. The excitement in popular music springs from the mixture of repetition and novelty, and Springsteen’s usual aversion to doing exactly what the public wants has prevented him from seeming even more like a guy playing Bruce Springsteen in a Bruce Springsteen movie than he already inevitably does. In fact, one of the things that’s going on beneath the surface of this record is that the E-Street Band is at times, in a sense, playing the part of the Castiles—the still-enduring band standing in for the members of the long-lost one. On first listen, I wondered whether they should have assumed that mask a little more fully on some tracks, calling back here and there to the mid-to-late-1960s sound of the earlier group, and had fun with the conceit a bit in the vein of, say, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I soon realized that would have jarred with the undercurrent of loss and mourning—but Springsteen came up with an even more unexpected twist that fulfills that time-travel function, while destabilizing E Street triumphalism in a subtler way.

That was his choice to scatter, among the album’s mostly tight dozen tracks, three that come from nearly five decades ago—songs written before his 1973 solo debut record that have never before been officially recorded and released. Like the ones on Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J., these pieces are sprawling, baggy, confusing, and ecstatic, phrased in snakey multisyllabic lines straight out of mid-’60s Bob Dylan, often with good-timey Americana choruses that recall the Band. They shouldn’t have any business on this record, but with the equal treatment the E Streeters give them, and with the singer somehow triangulating his youthful rushing drawl with his septuagenarian stadium rasp, remarkably they do. Instead of seeming like anachronistic throwbacks, they infuse the album with a sense of unpredictability that’s been difficult for the mature writer to capture ever since he nailed the knack of making songs feel more like inevitabilities. I’m not sure what “If I Was the Priest” is supposed to be about, but I’m very glad that the Virgin Mary is in the middle of it offering a “personally blessed balloon.” I do get what “Song for Orphans” and “Janey Needs a Shooter” (a song Warren Zevon kept pestering Springsteen to hear in the 1970s to no avail, until he finally just wrote his own version) are about—faux-prophetic pontification and loverman posturing, respectively—but they go at it by such roundabout paths that I get a dizzy high keeping up. On an album so much about grieving for lost youth, they bring the bona fides, saying here, this is what it was, all this wild-eyedness, all this chutzpah, all this possibility. But Springsteen and company can deliver that now with an authority a green, grasping 22-year-old couldn’t have reached.

In turn, though, the old songs do point up how many of the new ones lack the same originality. A songwriter who once seemed never to have a thought he didn’t immediately put through a hundred backflips (compare the Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town making-of documentaries to this album’s) now seems to settle for cliché all too easily. In part that’s because he has too much life behind him not to be dwelling on eternal verities. But an album that starts with the key line “One minute you’re here/ The next you’re gone” and closes with a gloss on Lead Belly’s standard “Goodnight, Irene” refrain “I’ll see you in my dreams” is reprising a lot of ultra-familiar sentiments. And when he endeavors to swell them up to Springsteen-epic size, they can seem more strained than grand.

The worst case here is “House of a Thousand Guitars,” which attempts to invoke a hopeful image of music as a holy meeting place where differences can be set aside and the predations of the powerful escaped. But that central phrase doesn’t soar, partly because it doesn’t flow phonetically enough to carry the freight, and also because in 2020 a thousand frankly sounds like too many guitars. Guitars are no longer the universal instrument of the common people, if they ever were, so a thousand of them sounds as oppressive as it does utopian—like a retired white boomer’s fantasy collecting obsession that’s driving his family crazy. There’s a similar try-hard-ness about “The Power of Prayer,” another song about the spiritual significance of music that I find more sententious than moving. It actually has some interesting existential detours within it, but the and here’s the moral pushiness of the refrain is reductive.

It’s always been a flub to regard Springsteen as a singer of protest songs.

In other cases, songs that are fine on their own simply feel like they’re making the same point the one a couple of tracks ago did. There’s a growing temptation to shrug, and I start to long for another more sensual song (along with “Burnin’ Train”), or one about parenthood or marriage, for variety’s sake—his wife is one of his bandmates, after all, so it wouldn’t be far off theme. The juxtaposition with the early Dylan-damaged songs makes me think, too, of the contrast with the artist’s youthful hero—Uncle Bob has only gone on getting weirder as he’s gotten older, as his album earlier this year amply showed. With Springsteen, by contrast, it can seem like the regular Joe costume that he strategically suited up in decades ago has kind of sealed around him, and suffocated his imp of the perverse.

Still, there were good reasons he put it on in the first place. Hailing from a working-class family and town, he quickly came to want to use his creative-oddball powers to represent voices that rarely can be heard for themselves. Along with his genius for showmanship, his ability to empathize and find narratives for ordinary experience—despite, from the first, his refusal to live a mundane life himself—is why he’s Bruce Springsteen and a thousand other guitar guys are not. Aging and death and losing some people and cherishing the ones you still have around you (with the E Street Band sonically incarnating those companions)—none of that is trite, and neither is addressing it in direct and simple terms, accessible across all kinds of social categories. Many people are going to hear their lives in it, and often I do too.

Part of my initial reaction to getting more memoir material was feeling vaguely let down that Springsteen was offering more self-reflection amid collective crisis. But as he told Rolling Stone in September, the fact is that a bundle of topical anti-Trump songs from him would be “the most boring album in the world.” It’s always been a flub for part of his audience, the music press, and at times Springsteen himself, to regard him as a singer of protest songs. He’s hit that mark a couple of times—most of all with “American Skin (41 Shots),” a song about the 1999 police shooting of Amadou Diallo that’s continued echoing in this year’s Black Lives Matter protests. But he’s not at his best when he tries to bear the mantle of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and early Dylan. Springsteen’s most resonant political material comes not through noble rhetoric but via his personal interest in life stories, whether his own or people he’s known or characters who come to him, within his carefully guarded class solidarity. And as he also told Rolling Stone, his instinctive populism has been put to the test in the Trump era: “I’ve got a little less faith in my neighbors than I had four years ago.”

So not making the predictable political album was, I think, the other clever decision Springsteen made with Letter to You. However (aside from one sidelong reference in “House of a Thousand Guitars”), he did reach back to an unrecorded song from the pre-Trump years to offer “one that stood in for the album I didn’t make.” That is “Rainmaker,” a song about demagoguery but more vitally about what makes people crave a demagogue, about those neighbors it’s hard to keep faith in. He sings, “Rainmaker, a little faith for hire/ Rainmaker, the house is on fire/ Rainmaker, take evеrything you have/ Sometimes folks need to bеlieve in something so bad, so bad, so bad/ They’ll hire a rainmaker.” It reminded me of what I read this week in an essay by retired union worker and sometime music writer Tom Smucker:

Politics that propose a too-small solution to a too-big problem and call it realistic, make the whole idea of realistic sound suspicious. Gaslighting working people about jobs lost from de-industrialization can push folks looking for an explanation towards the darker corners of our national mythology. If it’s true that your good job is never coming back, why not believe a lie?

Within the sound of this album, in the sound of the E Street Band, despite what sometimes might seem like too-small meditations, there is always a refusal to settle for an inadequate scale, to make the paroxysms and paradoxes of just living in this world sound like a petty business. Many people—and I’ve been one of them sometimes—hear in Springsteen’s scope and bravado its own kind of demagoguery. (They’re the ones who say they only like Nebraska.) His reluctance, ever since Born in the U.S.A., to keep making albums that have that widescreen magnitude testifies to his own hesitations about that. On Letter to You, unusually, he’s insisting on melding the micro and the macro together, to make the loudest noise about, often, the most internal things. It is its own kind of strategy, a little like a buttress, a way of holding on until something gives way. As that faux-prophetic or maybe just plain prophetic young man wrote in “Song for Orphans” nearly 50 years ago, “The lost souls search for saviors, but saviors don’t last long.” There are some fake saviors now in his beloved country that have to be gotten out of the way of the changes that need to come—and maybe after that, this long-laster will be able to take his gaze off the rearview and shift into a new gear.