51 years after “Creem” published its first issue, a documentary four years in the making is finally about to rear its unwashed head and peel back the beer-soaked curtain on the music, the mayhem, and the food fights that forged the magazine’s legacy

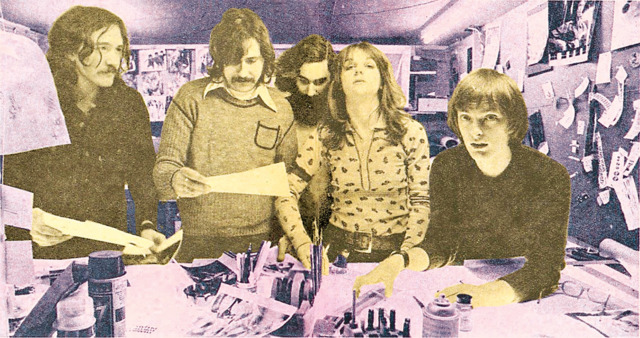

The Creem team (from left): Charlie Auringer, Lester Bangs, Ric Siegel, Jaan Uhelszki, and Dave Marsh.Photo: Richard Lee

The Creem team (from left): Charlie Auringer, Lester Bangs, Ric Siegel, Jaan Uhelszki, and Dave Marsh.Photo: Richard Lee

Let’s get a few things straight.

Subscription kid-turned-writer and unofficial KISS correspondent Jaan Uhelszki wasn’t a goddamn groupie in tight jeans with a tape recorder; and editor Dave Marsh may have coined the term “punk rock” and played the Who’s “I Can’t Explain” 23 times in a row during his stint at a college radio station, which got him fired; Barry Kramer — an unyielding capitalist, agent of controlled chaos, and the reason we came to love an anthropomorphic milk bottle like it was our deranged love child — was nothing if not a beautifully contentious and gifted ringleader; and untamed prolific rock critic Lester Bangs — as in the Lester Bangs — didn’t set out to be anybody’s fucking hero.

As for Creem — former home to this band of misfits and the Detroit-founded rock rag that cheekily touted itself as “America’s Only Rock and Roll Magazine” as a “fuck you” to the prim and polished musings of rival Rolling Stone and held a megaphone to its audience’s ears wailing with off-beat humor, unmerciful flagellation of untouchable rock gods, hands-on reporting, sexual irreverence, and unrelenting love of music, the good, the bad, and The Runaways (whose debut record was famously panned by Creem writer Rick Johnson: “These bitches suck. That’s all there is to it.”) — it lives on, motherfuckers.

Fifty-one years after Creem published its first issue and 31 years after having printed its last (and 10-plus years after an emotional and unsexy battle over intellectual property rights), a documentary four years in the making is finally about to rear its unwashed head and peel back the Boy Howdy Beer-soaked curtain on the music, the mayhem, and the food fights that forged Creem magazine’s legacy, which solidified that rock stars are never our friends.

Directed by Scott Crawford (a punk aficionado, Creem devotee, and the dude who once said a great rock writer should be “a tastemaker, not a bootlicker”), co-written by Uhelszki (trailblazer and one of the original Creemsters), and produced by JJ Kramer (son of Creem‘s founder, Barry, who died when JJ was just 4 years old), Creem — America’s Only Rock and Roll Magazine traces the publication’s history from ramshackle beginnings in Detroit’s Cass Corridor in 1969 (where founding editor Tony Reay, an employee at Kramer’s head shop Mixed Media, came up with the name Creem, a playful nod to his favorite band, Cream, as well as yet another middle finger to Rolling Stone, and convinced Kramer to put his money into kickstarting the mag), to its stint at a farmhouse in Walled Lake, where the writers and editors worked and cohabitated like the hippies they were not, to the posh-ish and professional-ish office space in tony Birmingham, a final resting place of sorts for the paper before ownership switched hands and eventually folded in 1989.

The film expertly enlists those tenacious staffers who worked tirelessly to make Creem happen — many of whom worked insane hours, made dick for pay, and endured the magic of collaboration and wild outbursts from clashing egos — and those hungry outsiders that, like the film’s director, discovered Creem at newsstands while left unattended by preoccupied parents and inhaled the rag’s every page. R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe appears in the film to credit his entire music career on having discovered the alternative world Creem gave access to, one in which people like Alice Cooper and Iggy Pop were as good as royalty and Grace Slick could slip a nip, and where writers could boldly critique sacred cow — er, Beatle — Paul McCartney’s decision to perform live with then-wife Linda as being a “blow for feminism” and “inverse sexism of the most emetically patronizing kind.”

“I mean, Creem was punk rock before that was even a word, you know, so just in their attitude and their approach. All of that really resonated with me,” Crawford says. “I mean, I was such a misfit, outsider kind of kid. It was like my Bible.”

Crawford recalls concealing his copies of Creem inside other magazines so that he could read without parental repercussions and later, more specifically found himself pouring over Bangs’ writing, which he describes as being “snotty as hell and kind of bratty,” which was a lot like the music Crawford was into at the time. But beyond the attitude, Crawford says Bangs resonated with him because of how his music writing made him listen to music.

“He was able to describe an album in a way where I could hear it without actually hearing the album,” Crawford says. “And that’s the real gift that he had.” Before going full-time at Creem, Bangs was a contributor at Rolling Stone, where he submitted several scathing reviews of albums like MC5’s Kick Out the Jams, Black Sabbath’s self-titled debut, and the one that got the California native canned, Canned Heat’s The New Age. During what would be his final interview in 1982 with Jim DeRogatis, rock critic and author of Let it Blurt:The Life & Times of Lester Bangs, America’s Greatest Rock Critic, Bangs said he knew Rolling Stone was “a piece of shit” from the beginning and his reviews “stuck out like sore thumbs.” (In the same interview, when asked if he enjoyed his stay at Creem, Bangs said he hated it. “It was a horrible place,” he said. “It was one of these kind of setups where you have a bunch of idealistic young people in the late era of hippiedom and a guy comes in who sees that he can make a lot of money off of their idealism. … There were a lot of things that were real sick about it.”)

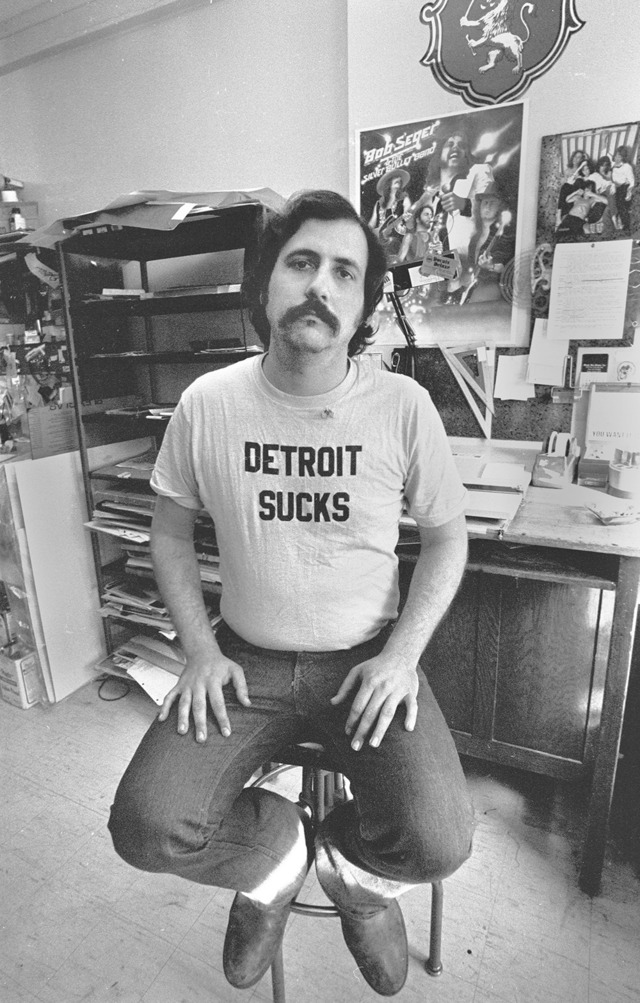

Lester Bangs in his iconic T-shirtPhoto: Charlie Auringer

Lester Bangs in his iconic T-shirtPhoto: Charlie Auringer

Music, first and foremost, though maybe only second to unflinching truth-telling, was the lifeblood of Creem, not just in its content but as it related to its general ethos, with much of the magazine’s staff operating as if they were in an actual band. You had the lead singer, which may have been Marsh but could have been Bangs. However, it’s more likely that Marsh was lead guitarist, with someone like Ben Edmonds or Robbie Cruger on bass, with Barry as manager, Barry’s partner and wife, Connie, as the band’s faithful sound tech, with Uhelszki on drums (for no other reason than her ability to keep the rhythm while balancing multiple editorial responsibilities at once, like overseeing the news section, “Beat Goes On,” penning the movie column, “Confessions of a Film Fox,” writing monthly reviews and features, contributing to photo captions, among less glamorous work like copy editing), all while seated next to a cough-syrup fueled Bangs; they both started working at Creem on the same day.

“When Lester would interview Lou Reed, he would always make us go with him. I remember it was like this group thing, I can’t believe either of them thought it was OK, but I remember sitting there, really uncomfortable, and Lester called him a little insect to his face,” Uhelszki says. “And it was like, you could see him sputtering, but that was Lester’s way, he would do anything to elicit a story. I mean, we were all a little bit like that. It’s like, back then, journalism was a contact sport, at least for us.”

Like many of the original Creem teamsters, Uhelszki didn’t finish college, though she did start attending Wayne State for journalism after she got hired at Creem when The South End, WSU’s student newspaper, said she didn’t have enough credentials or experience to write for them and that she should “walk down Cass Avenue to Creem because they didn’t care about things like that.” She recalls one of her last journalism class assignments, which was to cover a wrestling match, and instead of doing it herself, she passed it along to Bangs, who scored Uhelszki a lukewarm “B.”

“We used to have an ad in the front of the magazine, and it said, ‘We ain’t got nothing you ain’t got, so what do you got?’ meaning we take submissions from anybody, which is pretty much how I got there. I thought, well, I want to write — I mean, I’ve been writing since the fourth grade, so, you know, let me loose,” she says. “It took me a while to get there, but that was it.”

For her first Creem assignment, Uhelszki was sent to cover a press conference held by Motown crooner Smokey Robinson. Robinson was set to announce that he was going to split from his group, the Miracles, to embark on a solo career. Marsh, who was editor at the time, gave her just one day to turn the story around so she wouldn’t, as he says in the doc, “chicken out.” The result? A love letter from Uhelszki to Robinson, which ran as a cover story in 1972.

“Everything was ripe for a review,” Uhelszki says. “It was a time of me-journalism, where the writer was as important as the subject. I guess my breakout story was when I convinced KISS to let me go on stage with them. And they actually said, yeah. You know, to this day, I still can’t believe they said yes.”

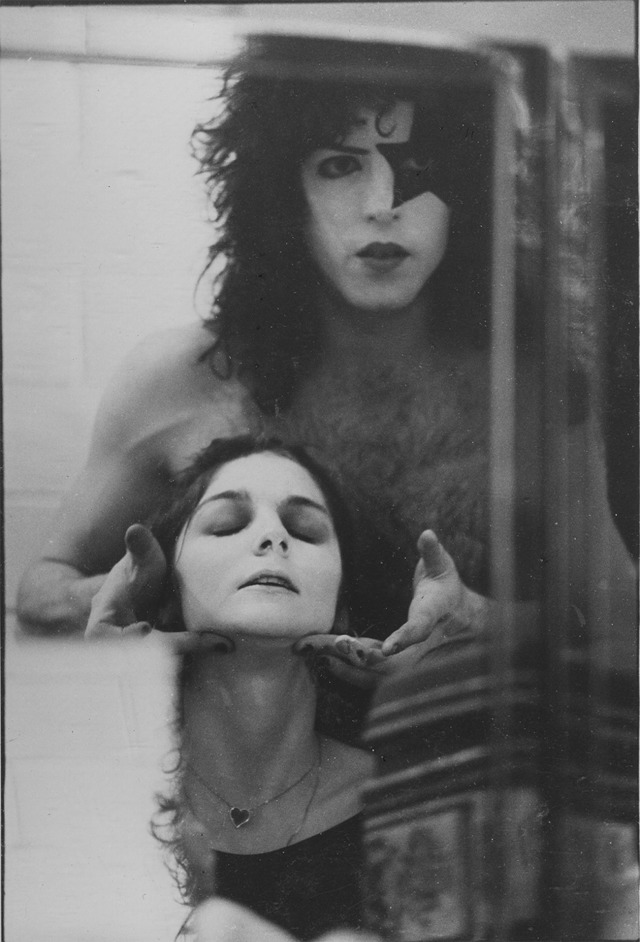

The story, “I dreamed I was on stage with KISS in my Maidenform bra,” ran in August 1975 and detailed Uhelszki’s journey pitching the idea to the vice president of Casablanca Records, and the band’s Paul Stanley, Ace Frehley, and Gene Simmons fussing over perfecting Uhelszki’s KISS makeup — a mish-mash of each member resulting in Uhelszki looking like some starry-eyed bat/cat hybrid before being shoved onto a stage in front of 5,000 screaming fans somewhere in Pennsylvania. She held an unplugged guitar, jumped around the stage, nudging KISS from their mics like one of the guys. After her performance debut, Stanley joked that she looked like Minnie Mouse up there, while Simmons applauded her scene-stealing prowess. She was the first and, so far, only music journalist to perform as a temporary member of KISS.

Jaan Uhelszki gets the KISS treatment with Paul Stanley.Photo: Barry Levine

Jaan Uhelszki gets the KISS treatment with Paul Stanley.Photo: Barry Levine

Being underestimated was a common theme for Uhelszki, who says being one of the first women in rock journalism came with a frequent dose of what she calls “an early version of mansplaining.” Not from her cohorts at Creem, where income was basically “economic determinism,” where everyone, at the mag’s peak, made about $22.75 a week after taxes, thanks to lover of cheap labor Barry Kramer, who she playfully describes as being “enlightened about women” and an “equal opportunity visionary and abuser.” The sexism she experienced was out in the real world, or at least out in the rock world. She recalls the time that Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman answered his door for an interview wearing nothing but a towel and refused to put clothes on — though, she’s quick to mention that when she interviewed Sharon Van Etten years later, she, too, answered in her towel, but eventually got dressed.

“[The men] wouldn’t think I’d have any kind of musical knowledge or any kind of context,” Uhelszki says. “And they would really think that I was a groupie. Every female was treated that way. I mean, it was amazing. I didn’t really think of it as being sexist; I was really just so happy to actually be able to do what I wanted to do with my life because there was no rock journalism. And it was pretty much that I really lucked out meeting all these people who wanted to do the same thing.”

Uhelszki credits youthful “euphoria and joy” as being her driving forces to work hard with zero work-life balance or personal space, as were the conditions associated with Creem‘s various communal workspaces. Once the magazine moved its operations to Birmingham, she says only then were they able to “move up.” She recalls still having to occasionally sleep under her desk to meet deadline, but once in Birmingham, they all started to get their own apartments and places to live. Sales were up, and Creem was the No. 2 rock magazine in the country, just behind Rolling Stone. But this didn’t mean their codependency came to an end.

“Basically, we hung out together because who else are you going to hang out with when you’re working at night and, you know, we would go see shows together because that was work. We did a group thing. You know, we’d all go together, we’d leave together. We didn’t really want to be anywhere else,” she says. “And I didn’t even think of that as being funny. But I look at it now, it’s like, really? Were we a cult?”

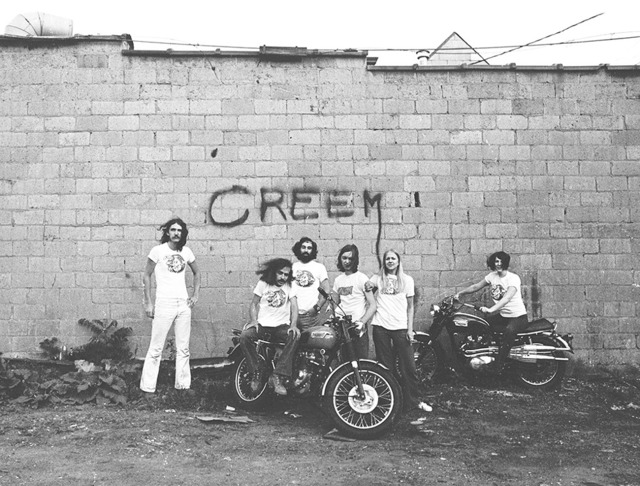

Creem magazine employees in 1969.Photo: Charlie Auringer

Creem magazine employees in 1969.Photo: Charlie Auringer

A typical issue of Creem might look something like this:

First, the cover: While Rolling Stone was peddling James Taylor and ’60s psychedelia to teens like the next cool drug, Creem put the faces and various body parts of David Bowie, Blondie, Bob Seger, Frank Zappa, KISS, Iggy Pop, and Alice Cooper on its covers. Turn the page, and you’ll find yourself a saucy little milk bottle with legs, arms, and a goofy smile that could convince you to take any number of unidentifiable pills from the coffee table. We mean, this guy is everywhere. This was Boy Howdy, Creem‘s mascot, which Barry had commissioned from legendary underground illustrator R. Crumb, who allegedly drew up the little dude in exchange for $30 and a shot of penicillin.

Then comes “Rock ‘N’ Roll News,” a vertical that delivered the who’s who, what’s what, and which band had called it quits or which Rolling Stone member had a ruby filling implanted in his upper right incisor (hint: It ain’t Keith). For more fleshed-out stories, though still bite-sized, “The Beat Goes On” included everything from Ted Nugent’s butchering habits, to hotel clashes between Faces pianist Ian McLagan and angry boxing fans, to Patti Smith crediting Creem for her rise to Godmother of Punk status after the mag dedicated three pages to her poetry, to one writer having joyfully discovered The Babys’ 1977 record Broken Heart. Writer Robert Christgau had a review column, the “Christgau Consumer Guide,” where he ranked records and gave Bruce Springsteen’s Born To Run an “A.”

Then came Creem’s Profiles. This is where the mag would feature stars of all levels — we’re talking Cheap Trick, Rod Stewart, Cheech and Chong, The Clash, and Todd Rundgren. Here they would be featured posing with a can of Boy Howdy Beer. Now, this ain’t a real beer; it’s a “bumper sticker” slapped on another beer can. Smoke and mirrors. Anyway, the Creem’s Profiles asked stars questions like their age, profession, hobbies, favorite quote, and the last book they read; often, these people hadn’t read a book anytime recently, so writers would sometimes make this one up.

“Stars Cars” was another Creem staple, in which stars would, you guessed it, pose with a car. Sometimes it was their car, in the case of Aerosmith’s Joe Perry, who was featured in the driver’s seat of his 1967 periwinkle blue Corvette, which he had crashed into a wall before the shoot but snapped a pic with it anyway. George Clinton posed with a garbage truck, wearing silver boots, and the Ramones draped their gangly limbs over a red, rusted-out beater with trash in the trunk and no back window.

The features were the real bread and butter of the mag because you had folks like Uhelszki hitting the road with Led Zeppelin and reporting from within; Susan Whitall’s intimate profile of Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders, another musical outsider; and Barry Kramer himself, who toured with Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels and survived a John Wayne-esque brawl at a gig in North Carolina.

Creem had film coverage, too, which had quippy one- or two-liners about what was going down in Hollywood town. Chevy Chase did what? Leonard Nimoy said that? What is Cher up to? Then, of course, the reviews — perhaps the section you’d skip ahead to so you knew which records to buy and which ones to burn.

Perhaps one of the most beloved sections of the mag was supplied by its readers, including, Joan Jett, who famously responded to a negative review of The Runaways’ debut (the one where they’re referred to as bitches that suck) via the mail section. And it wasn’t uncommon to encounter a message like the one penned by Mrs. Oliver Canett, of Dallas, Texas, whose letter was published in the May 1972 issue with T. Rex on the cover.

Dear Creem: Please cancel the subscription for Holly Beal to your sick magazine. You and your kind are to be pitied for polluting the minds of our youth.

The Post Office Department has been notified not to deliver this filth to our home.

May God help you before it is too late.

Creem‘s Ed Ward replied: “Too late for what?”

Crawford, whose previous work includes Salad Days: A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980-90), he had known for years that there was a Creem story waiting to be told.

“The writers were just as important as the artists that they covered. That was always fascinating to me,” Crawford says. “So to get to know some of these folks, it was interesting. You have this idea of how they’re going to be, and for the most part, they were thoughtful, intelligent, insightful people who still — to this day — love music and love writing about it, or at least love talking about it.”

An intellectual property attorney by trade, JJ Kramer spent years fighting to obtain the rights to his father’s company.Photo: Courtesy JJ Kramer

An intellectual property attorney by trade, JJ Kramer spent years fighting to obtain the rights to his father’s company.Photo: Courtesy JJ Kramer

JJ Kramer had been approached in the past to do a Creem documentary or similar projects. He says he didn’t “vibe” with those directors that had approached him, in terms of the story they would tell and their overall vision. Not to mention, some legal hangups made Creem — the legacy brand — untouchable, even to JJ, who, as a toddler, was named chairman of the board of the magazine after his father died. When Connie Kramer sold Creem and its intellectual property rights to Arnold Levitt in 1986, things became muddled in terms of who owned what, as the brand was split off into various pieces of IP, with former Creem photographer Robert Matheu securing licensing rights in 2001 to bring the magazine back.

JJ is, as he describes, is “the suit” of the family. When he’s not producing Creem documentaries, he’s serving as an intellectual property counsel for Abercrombie & Fitch, a skill set that came in handy when overcoming what became an “arduous, draining, and emotional” decades-long process for not only tracking down the fragmented brand, but regaining full intellectual property rights to his inheritance: all things Creem.

“Once that happened, it was like, OK, I’ve got all the rights, what do we do with it?” he says. “The first thing was, let’s go make this film. To me, that was a great first opportunity to put my stamp on the Creem legacy, and then use that as a jumping-off point for more stuff to come down the road.”

Thanks to some degrees of separation, Uhelszki introduced Crawford and JJ, both of whom clicked immediately when it came to what a Creem movie would look and feel like, not to mention they aligned on core beliefs like a great rock writer is one that can take a swing at a rock star and go for broke doing so, and in recognizing the magazine’s emotional center.

“He immediately recognized that it’s a story about the people behind it,” JJ says of Crawford. “We’ve got these incredible, outspoken characters in the film. So it’s about those characters. It’s about Detroit and that blue-collar, roll-your-sleeves-up, having-a-ginormous-Detroit-sized-chip-on-your-shoulder approach to things. And when he explained to me how he wanted to approach all that, it immediately resonated with me and I jumped in headfirst.”

What Crawford set out to do, however, was to learn more about Barry. Crawford says much was known about Marsh and Bangs, who he sees as the unofficial faces of the magazine. But Barry didn’t quite position himself for the spotlight in the way that Creem‘s writing staff or the rock stars they wrote about had. Instead, he poured himself into how to make and sustain a successful business, as both a master of manipulation and dysfunction. For the most part, he pulled it off — until he couldn’t.

“At times when I was working on the film and hearing stories, I didn’t understand how that circus functioned,” Crawford says. “But you can see that it didn’t function at all, at times. I mean, there were actual fights. I didn’t include half the fistfights — I mean, there was a lot more.”

But the documentary was not a vehicle solely for Creem fans (and virgins) to get a behind-the-scenes jolt of debauchery that made the magazine go round and round The heart of Creem: America’s Only Rock and Roll Magazine, served as a way for Barry’s son, JJ, to meet his father in a way he may not have otherwise been afforded.

“I’ll be honest with you, more than once we had to stop because I think, collectively, we all just had lumps in our throats as we were interviewing, JJ,” Crawford recalls. “That’s why having JJ in the film was so important because it was reminding people that, throughout the course of this film, Barry’s son is getting to know his father.”

In 1981, Barry Kramer overdosed in a motel room after putting a plastic bag over his head and inhaling a lethal amount of nitrous oxide. He was 37 years old.

JJ breaks down discussing it in the film: “It’s a fucking ugly way to go.”

Bangs would die a year later, at the age of 33, of an accidental overdose involving a cocktail of Valium, Darvon, and Nyquil. Just as Barry has been immortalized through the Creem documentary, Bangs, too, was immortalized in 2000’s Almost Famous. The semi-autobiographical directorial entry by Creem and Rolling Stone writer Cameron Crowe, who pegged Philip Seymour Hoffman to slip into Bangs’ iconic “DETROIT SUCKS” T-shirt and his needle-sharp wit to serve as the mentor who, in real life, wrote disparagingly about being idolized and spoke disparagingly of being the one to do the idolizing.

“The fact is that Lou [Reed], like all heroes, is there for the beating up. They wouldn’t be heroes if they were infallible, in fact they wouldn’t be heroes if they weren’t miserable wretched dogs, the pariahs of the earth, besides which the only reason to build up an idol is to tear it down again, just like anything else,” Bangs writes in an essay featured in Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung. “A hero is a goddam stupid thing to have in the first place and a general block to anything you might wanta accomplish on your own. Plus part of the whole exhilaration of admiring somebody for their artistic accomplishments is resenting ’em ’cause they never live up to your expectations. Plus which they all love the abuse, they’re worse than academics, so the only thing left to do is go whole hog nihilistic and tear everybody you ever respected to shreds. Fuck ’em!”

Looking back, JJ admits that he probably should’ve engaged in some kind of therapy to deal with the early and traumatic loss of his father, not to mention the close involvement he would grow to have with his father’s second family, the revolving door of misfits at Creem, without whom Barry could not have done what he did, which was, ultimately, kickstart a rowdy rock ‘n’ roll revolution. JJ recognizes that, through talking with the film’s 40-plus onscreen and offscreen subjects and sources, it was as good as therapy, and with the film behind him, he can now set his sights on more Creem-related projects and opportunities because, as he says, the documentary is but a fraction of what happened behind the scenes — like when Creem‘s Walled Lake farm office was under surveillance by the FBI in the ’70s due to Creem‘s affiliation with activist John Sinclair and the White Panthers. (Former Creem editor Bill Holdship reported that Barry had told the government to go fuck themselves when they contacted him about being a snitch.) There’s a whole story behind the relationship between Lou Reed and Lester Bangs, too.

JJ says there are “so many threads” to pull on and that he’s finally ready to let it unravel.

“I had always been straddling this line when it came to Creem,” he says. “It was something that, in a lot of ways, you know, as a child, I wore as a badge of honor. It was cool to talk about and tell my friends that my dad started this rock ‘n’ roll magazine, but I probably subconsciously didn’t start digging beyond that until I was an adult.

“It may sound a bit weird to say this, but I feel like my whole life I was both running towards Creem but also running away from it because of what it meant to really get into the trenches and sort of follow my father’s trajectory from when he was this incredible success story at the beginning — and the ending, where he was obviously very sick.

“This has been a very therapeutic process for me,” he adds. “It’s been incredibly emotional, but it’s everything I signed up for. It’s not only taught me about my father, but it’s taught me a lot about me. It’s been a really incredible ride.”

Boy Howdy! Creem — America’s Only Rock and Roll Magazine is available on video on demand on Friday, Aug. 7. You can get tickets here.

This story originally appeared in our sister publication, Detroit Metro Times