During graduate school at UCLA, I sometimes played hooky and headed to Schoenberg Hall (the music department building) to check out their Ethnic Folkways vinyl. UCLA had and still has a busy ethnomusicology department, with a library stocked with treasures. I would pull LP’s off the shelves, put them on the turntable, and listen with headphones on. I didn’t know much about African or Caribbean music back then, so some of the sounds were novel and strange. I found others unlistenable, especially those with the rough portable reel-to-reel tape recordings, the single microphones, and the primitive settings for recording music (outdoors, no electricity, etc.).

My visits to Schoenberg Hall took place in the mid-1970’s, long before the term “world music” was devised. Fifty years later, this traditional music is less “foreign” to us given the amount of available music from every corner of the world and the shrinking of the planet with air travel, global telecommunications, and other factors that I covered in my book Rhythm Planet: The Great World Music Makers.

A pioneering man named Moses Asch started Folkways Records in 1948. He was a true explorer, out to capture folk and ethnic music from far-off lands and more. It would be an understatement to say that he succeeded. Thanks to Asch, we can trace the growth of world music from these early recordings. The Folkways archive is now under the care of the Smithsonian Institution, which acquired the recordings when Asch died in 1986.

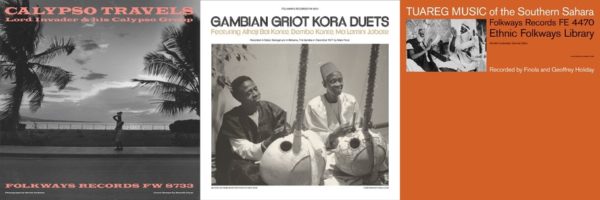

Smithsonian Folkways, the music label for the Smithsonian, launched a vinyl reissue series in 2018 to spotlight hidden gems and bring back some of the most important albums released by Folkways. The first three re-issues out of the gate for 2020 highlight seminal recordings from the Caribbean, the Sahel, and Gambia. Each deluxe album comes in a cardboard jacket with artwork reminiscent of the original albums. The 180 gram vinyl shows respect as well, but keep in mind that some of these are field recordings captured in less-than-ideal settings. Here are my notes on the releases, as well as a short playlist featuring a couple of tracks from each album.

Lord Invader – Calypso Travels (1960)

Anybody visiting Trinidad and Tobago (or the Trinidadian community in NYC) during carnival will be familiar with calypso music. I’ve heard that rap music derives from calypso, the latter commenting on current social and political events, with self-boasting and funny story-telling songs. Take Lord Invader’s songs on this last album that he recorded before his death in 1961. His lyrics mention Fidel Castro, the new Cuban leader at the time, as well as Egyptian strongman Gamal Abdel Nasser. There’s a song about the Little Rock, Arkansas school integration crisis of 1957 and others about Lord Invader’s travels through Europe, where he was popular and frequently toured. There’s a funny song about dancing with an attractive woman in a bar who turns out to be a cross-dresser. The music style is very jazzy, with African and Afro-Cuban rhythms. Harry Belafonte, Robert Mitchum, and Maya Angelou all had scored calypso hits in the U.S. by this time, so the music on this album is probably the most familiar of the reissues, and certainly the closest to home. By the way, I like that every calypso artist seems to have an honorific in their name—Lord Invader, Young Tiger, Mighty Sparrow, Lord Kitchener.

Tuareg Music of the Southern Sahara (1960)

Tuaregs are the desert nomads of North Africa. This 1960 album was recorded right around the time of Malian independence from the huge swath of territory previously known as French West Africa. So instead of Mali, the album title refers to the Southern Sahara.

I find Tuareg Music of the Southern Sahara to be the most intense of the reissues. We hear piercing ululations by the assembled women, lots of vocal distortion, and no electric guitars as in modern Tuareg desert bands like Tinariwen and Terakaft. This is music with very old and deep roots. In the liner notes of the original album we read, “Out of this cauldron of history the Tuareg of today have emerged, more or less unscathed, their habits, dress, customs, beliefs and language (Tamashek) little different from what they must have been 2000 years ago.”

On this raw album, it’s just drums, handclapping, and vocals. On one song you can hear camels braying. Listeners will be startled by the women’s ululations. There are dance songs, love songs, wedding songs, and hunting songs. For anybody who enjoys the modern Tuareg desert grooves of Tinariwen and others, this is a good way to return to the roots of this rich and intense music.

Gambian Griot Kora Duets (1977)

A jewel among West African traditional instruments, the kora is a large gourd covered in goatskin and ornamented with beautiful beadwork. It has 21 strings and can be tuned in different ways. Koras are the prime instrument of griots, the traditional oral historians and storytellers who often performed for the ruling classes, but also sang about the phenomena of daily life affecting regular folk. The performers were also called jalis.

Gambian Griot Kora Duets showcases kora music as oral history and storytelling, its traditional province, featuring the artists Alhaji Bai Konte, Dembo Konte, and Ma Lamini Jobate. This 1977 album differs from modern kora albums, which often focus on instrumental music rather than the more ritualistic jali/griot aspect. There are tracks praising the artists’ homeland, early Mandinka songs about kings of the past, a classic song composed during World War II. On some tracks the musicians’ wives join and sing the lyrics. The sound is superior to the earlier Tuareg album, as it was recorded using a more modern Sony 2-track tape deck and four condenser microphones.

The Folkways kora duets album was released long before general audiences knew about the kora. In 1979, its original release date, I was only aware of kora albums on French labels such as Arion, such as those by Lamine Konte. I remember his albums from working at Vogue Records here and then living in Paris, where I haunted FNAC and other record stores. All that has changed with the profusion of albums celebrating this elegant African harp-lute. For those who want to explore further, Malian kora master Toumani Diabaté has recorded magnificent kora albums for the World Circuit label. I love Toumani’s album with his son Sidiki, as well as his album with the Symmetric Orchestra. I also love the African strings group 3MA, which includes kora player Ballaké Sissoko. The kora emits a magical, enchanting sound that makes it a perfect instrument to pair with pianos and many other Western instruments. Some examples of these interesting partnerships include piano, Welsh harp, and cello.

PLAYLIST NOTES

Tuareg Music of the Southern Sahara (1960): In the song “Ilougan,” people express their emotions while watching camels dance. The ululation of the gathered women shows their appreciation for the spectacle. Camels are the most important animals in Tuareg culture. In the wedding song, “Arouia Idaoua Ouf Emri,” you can hear a camel braying as if enjoying the festivities.

Lord Invader – Calypso Travels (1960): Calypso songs mention current events, and the track “Fidel Castro” talks about the new leader of Cuba. “Beautiful Belgic” is about the artist’s travels through Belgium while on a European tour.

Gambian Griot Kora Duets (1977): “Sutukung Kumbu Sora / Solo” names the various villages a wealthy Gambian man named Kumbu Sora (Alhaji Bai Konte’s father) lived in and visited. His son sings about it. “Darisalami Amad Fal,” also by Alhaji Bai Konte, honors a Mauretanian Sherifa (descendant of Mohammed). The artists’ wives join in on this track.