Advertisement

From blackface minstrels to the Velvet Underground to virtual reality: How a gritty neighborhood in New York always turned out the most vital music.

By John Strausbaugh

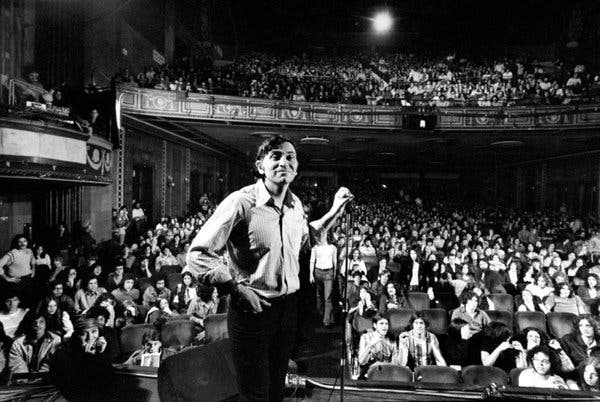

A new exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, “Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution,” celebrates the life and career of the iconic concert promoter with a wealth of photos, artifacts, and, of course, songs. New Yorkers might be particularly interested in the section on the Fillmore East, the hall at Second Avenue and East Sixth Street where, from March 1968 to June 1971, Graham brought a Who’s Who (including the Who) of the era’s top rock, pop and soul acts to the Lower East Side.

But the Fillmore East was nothing new; it was just the latest bloom in an astonishingly fertile musical neighborhood. The same conditions of poverty, high immigration and cheap real estate that made the Lower East Side such a notoriously tough place to live also helped to make it an incubator for all sorts of music, from the highbrow to the loathsome. Here, a handful of representative songs scattered across the years.

“Dixie,” Daniel Decatur Emmett, 1859

Yes, that “Dixie.” Alas, the first pop music stars from the Lower East Side were blackface minstrels. For all that minstrels went on about plantation life and their old Kentucky home, minstrelsy was in fact largely a northern, urban phenomenon that came out of neighborhoods like the Lower East Side, where poor whites and poor blacks lived crowded together and borrowed bits of each other’s music and dance.

The Elvis of early minstrelsy, Thomas Dartmouth Rice, was a son of Irish immigrants from the neighborhood’s infamous Five Points slum. His signature song, “Jump Jim Crow,” was a hit all over the world. One traveler claimed to have heard it in Delhi.

Daniel Decatur Emmett, a successor to Rice, said that he wrote “Dixie” one dreary night on the Bowery in 1859. Although Southerners quickly claimed it as a Confederate anthem, it was just as big a hit in the North, sung not only at Jefferson Davis’s inauguration but on the train carrying Lincoln to his.

“I’m Waiting for the Man,” Velvet Underground, 1965

In 1964, an immigrant from Wales named John Cale began sharing the $25 a month rent on a fifth-floor walk-up in the tenement at 56 Ludlow Street. It was there that he and a frequent visitor from Long Island, Lou Reed, formed the Velvet Underground in 1965, and wrote several songs that would appear on their debut album. Among them were “Heroin” and “I’m Waiting for the Man,” shockingly raw evocations of the dope culture that was rampant in the neighborhood in the mid-60s.

It’s worth noting that, accounting for inflation, the $25 rent that Cale split with a roommate in 1964 would be around $200 today. The average rent on a studio apartment on the Lower East Side is more than $2,000 now.

“Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” Yip Harburg and Jay Gorney, 1930

In the first half of the 20th century, Jewish immigrants and their children used popular music, including minstrel songs and blackface, as a way up and out of the neighborhood.

Irving Berlin (born Israel Baline in Belarus) was 5 when his cantor father, fleeing the pogroms, brought the family to the Lower East Side. Berlin was a singing waiter in a Chinatown dive when he earned 27 cents for his first published song in 1907.

George and Ira Gershwin’s parents also fled the pogroms. George’s first piano was an upright hoisted through a window of the family’s 2nd Avenue apartment. His first hit, “Swanee,” was a latter-day minstrel song Al Jolson sang in blackface.

Eddie Cantor, born Israel Iskowitz in an Eldridge Street tenement, emulated Jolson and often performed in blackface as well.

But perhaps none captured the neighborhood zeitgeist better than the Gershwins’ boyhood friend Irwin Hochberg, another child of Jews who’d fled the pogroms. Using his professional handle, Yip Harburg, he wrote the lyrics for two great songs that bookended the Depression, emotionally as well as chronologically. The bleak “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” (with music by Jay Gorney, yet another pogrom refugee) came out just as the Depression hit. His other big hit was the soaring “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” which appeared in 1939, just as the Depression was ending.

“Marquee Moon,” Television, 1977

In 1974, Hilly Kristal, another son of Jewish immigrants, changed the name of his dive bar Hilly’s to CBGB — Country, Bluegrass, Blues — with the odd intention of making it a country music outpost on the grungy Bowery. Instead, it soon became the birthplace of punk rock and new wave, launching the careers of such bands as the Ramones, Talking Heads, Blondie, and Television.

By the ’80s CBGB was a pilgrimage site for punks from around the world and a home to hard-core bands, including an early incarnation of the Beastie Boys. The club was well past its heyday when it closed in 2006, replaced by a John Varvatos shoe boutique, but is still widely lamented.

“Nutty,” Thelonious Monk Quartet, 1958

After World War II, painters, poets, and other creative types were drawn to the Lower East Side by the cheap rents. They brought with them a love of bebop and all new forms of jazz. The enterprising owners of the Five Spot, a typical Bowery dive bar at 5 Cooper Square, transformed it into a jazz club in the mid-1950s.

Innovators like John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Ornette Coleman and Charles Mingus regularly performed there, for audiences that included Jack Kerouac, Langston Hughes, Larry Rivers and Grace Hartigan. In live recordings from the club, like Monk’s playful bebop classic “Nutty,” recorded there in 1958, you can hear the tinkling of ice in cocktails and the hum of conversations.

“Changes,” Band of Gypsys, 1970

When Bill Graham opened the Fillmore East in 1968, several strands of neighborhood tradition wove together. He’d first come to New York in 1941 as Wolfgang Grajonca, an 11-year-old Jewish immigrant, orphan and refugee from Hitler’s Europe.

By 1968 he’d renamed himself, served in the army, and made San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium the premier rock venue on the West Coast. The 2,700-seat auditorium where he started the Fillmore East was built as a Yiddish theater in the 1920s.

Jimi Hendrix was still Jimmy James when he was discovered in a downtown club and whisked away to superstardom in 1966. On Jan. 1, 1970, he helped Graham ring in the new year at the Fillmore East with his new Band of Gypsys, recording songs like “Changes.” Before the year was out he’d be dead of an overdose.

“202 Rivington Street,” Genya Ravan, 1979

Genya Ravan came to the neighborhood in 1947 as Genyusha Zelkowitz, a 7-year-old in a family of desperately poor Holocaust refugees from Poland. She grew up in a fourth-floor cold-water walk-up at the corner of Rivington and Ridge Streets, learning her English by singing along with the radio.

By 1964 she was fronting the female rock band Goldie and the Gingerbreads, who toured Europe with the Rolling Stones. After that she co-founded the band Ten Wheel Drive, who played one of their first gigs at the Fillmore East in 1969. “202 Rivington Street” is a bluesy rock ballad about growing up tough but vulnerable on the streets of the Lower East Side.

“Drive By,” Eric Bellinger, 2016

At Jump Into the Light on Orchard Street, you wear a virtual reality headset to experience what may be the future of music. It’s a VR arcade on the street level, but upstairs is a creative studio where designers have been collaborating with music artists like Brooklyn’s Maria Brodskaya and the West Coast singer Eric Bellinger on exhilaratingly next-gen enhanced-reality live performances and immersive 360-degree music videos, like one for “Drive By.”

Michael Deathless, one of the club’s owners, said of the neighborhood’s future in 2018: “The people with an angle, they’re going to survive.”