Advertisement

Critic’s Notebook

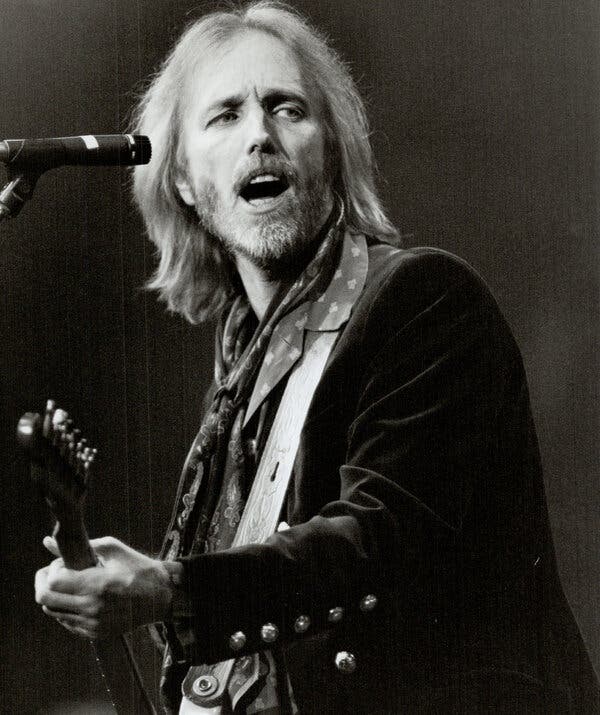

A deluxe edition of his blockbuster 1994 solo album spotlights the musician’s creative process, and the mind-set of a man at a crossroads.

By Lindsay Zoladz

One day in 1993, Tom Petty opened his mouth, and a new song came out, fully formed.

“I swear to God, it’s an absolute ad-lib from the word ‘go,’” he later told the writer Paul Zollo of the title track from his melancholic and masterful second solo album, “Wildflowers.” “I turned on my tape-recorder deck, picked up my acoustic guitar, took a breath and played that from start to finish.”

The extraordinary new collection “Wildflowers and All the Rest” lets listeners experience that mystical, intimate moment: The first home-recorded demo of “Wildflowers” is among the five-disc release’s many spoils. (There are also 14 more home recordings, a live album, a disc of alternate takes and unreleased recordings of the 10 other tracks that would have made the cut had “Wildflowers” become the double album that Petty initially intended.) In a murmured vocal, Petty sounds like a man fumbling for a light switch and never quite finding it, though a quick flash of luminescence brings a lyric that expresses something simple and true: “Far away from your trouble and worry,” he sings in his tender drawl, “You belong somewhere you feel free.”

Like a lot of great songwriters, Petty believed he channeled his music from somewhere else, so it wasn’t like him to immediately consider exactly who or what a new song was “about.” (“I hesitate to even try to understand it,” he said of his gift in Peter Bogdanovich’s 2007 documentary, “Runnin’ Down a Dream,” “for fear that that might make it go away.”) But some time later, Petty’s therapist floated his own theory: “That song is about you. That’s you singing to yourself what you needed to hear.”

That analysis, Petty recalled to his biographer, Warren Zanes, “kind of knocked me back. But I realized he was right. It was me singing to me.”

From the outside, in the early ’90s, it would have been surprising to hear that Tom Petty needed reassurance from trouble and worry: The wryly grinning rock star appeared to have the Midas touch. Petty was then entering his second decade with the Heartbreakers, the tight, rollicking band that he and some fellow North Floridian pals had formed in the early 1970s; in the years since, they had put out a long, consistent string of hit albums that seemed to hover somewhere above the music industry’s passing trends.

By the late ’80s, and his late 30s, Petty had not only met his heroes (Roy Orbison, George Harrison, Bob Dylan and Jeff Lynne) but formed a band with them, the Traveling Wilburys. He and Lynne had also recently recorded “Full Moon Fever” (1989), Petty’s first solo album, which they captured quickly with charmed and refreshing ease. His record label almost didn’t put it out because it didn’t think it was commercially viable, despite its first two tracks being “Free Fallin’” (!) and “I Won’t Back Down” (!!). Instead, it became his biggest seller yet.

And yet Petty was, throughout all the ostensible highs, outrunning some internal demons that overtook him the minute he slowed down. His two-decade marriage was failing. (His wife, Jane Benyo, had been with him since “the age of 17” — a fact that Petty’s friend Stevie Nicks had once misheard because of Benyo’s Florida accent; you can fill in the rest of the story from there.) Petty’s stormy relationship with the Heartbreakers drummer Stan Lynch was threatening the band’s future. And there were all sorts of intrusive memories that he’d been trying to bat away since leaving Florida, of a childhood with a sick, saintly mother and an abusive father whose version of Southern masculinity he could never quite live up to. In the respite after the Heartbreakers released the Lynne-produced “Into the Great Wide Open” in 1991, Petty entered the most searching and fertile creative period of his career.

“There was definitely tension in his life,” the “Wildflowers” producer Rick Rubin recalled of the album’s sessions in Zanes’s biography, adding that it “seemed he didn’t really want to leave the studio. Like he didn’t want to do anything else in his life. I think he wanted to take his mind off whatever was going on at home.”

But of course that all spilled out in the songs he was writing, which were at turns raw, funny, hopeful and, just below the surface, throbbing with an almost constant ache. “In the middle of his life, he left his wife, and ran off to be bad — boy, it was sad,” Petty sings atop the richly textured acoustic guitar and a lightly shuffling beat of “To Find a Friend.” (Ringo Starr just happened to swing by the studio one day and obliged to sit in.) By the chorus, though, Petty’s jokey, I-know-a-guy facade has fallen away and revealed a confession of startling first-person vulnerability: “It’s hard to find a friend.”

Petty had long proven himself to be a writer of incisive economy — a rock ’n’ roll Hemingway in tinted shades. He had a knack for assembling simple, everyday words into spacious and evocative phrases: Even on the page, to say nothing of all he brings to the recorded vocal, there’s an entire short story in the five words, “And I’m free/Free fallin’.”

One of the geeky joys of “Wildflowers and All the Rest” is observing Petty at the absolute peak of his songwriting powers, making small, intelligent tweaks to these songs in progress. Sometimes it’s a single world, a few letters. During the sessions, the guitarist and longtime collaborator Mike Campbell had brought Petty a driving riff around which he wrote a song he called “You Rock Me” — tentatively, because he knew that was an awful title. In the collection’s liner notes, Campbell recalls Petty keeping the problem of that lyric on the back burner for months, then one day he arrived at the studio with a monosyllabic eureka: wreck. “You Rock Me” is a cliché. “You Wreck Me” is a whole vibe.

Toggling back and forth between the home recordings, alternate takes and the completed album versions reveals Petty subtly moving puzzle pieces around: A hummed bridge melody from the title track’s demo finds its home in “To Find a Friend”; “Climb That Hill” moves through two different arrangements before being cut from the finished record. Perhaps most fascinating is the evolution of “You Don’t Know How It Feels,” which shifts from a somewhat pensive home-recorded ballad to, on the live album, an anthemic, smoke-’em-if-you-got-’em crowd-pleaser. In between, the recording that made the track a hit adds in the drummer Steve Ferrone’s indelible beat, as produced by Rubin, a co-founder of Def Jam Recordings. “The nature of the drum pattern, how loud the beat was mixed, spoke to the hip-hop producer in me at the time,” Rubin says in the liner notes, “and gave a new flavor to the Petty palate.”

Like its predecessor, “Wildflowers” was a hit: It went triple platinum in less than a year, making it Petty’s fastest-selling record. Even its staunchest believers weren’t expecting it to become such a smash. “I think the reason I was surprised,” Rubin said in Zanes’s book, “has to do with the idea of a grown-up making a good record. There were so few grown-ups making good records that it really stood out, for just that reason.”

Sometimes the songs arrive at certain truths before their singer does. “I’ve read that ‘Echo’ is my ‘divorce album,’” Petty told his biographer, referring to his 1999 effort, “but ‘Wildflowers’ is the divorce album. That’s me getting ready to leave. I don’t even know how conscious I was of it when I was writing it.” By that time table, then, “Wildflowers” is also prelude to the darkness to come: Petty’s debilitating depression, and a mid-90s heroin addiction he kept hidden from almost everyone in his life.

And so the deep despair is there, too, in the rich soil of these songs. But what makes it bearable, and makes the record so timelessly listenable, is everything else that’s mixed in: humor, wisdom, a little randiness and a palpable sense of hope. I still find the final song on “Wildflowers,” “Wake Up Time,” to be the saddest song Petty has ever written: verses of last-call, midlife musings (“You used to be so cool in high school, what happened?”) followed by a chorus’s inner-child yowl, “You’re just a poor boy, alone in this world.” But it’s also one of his most hopeful. By its end — in this big, calming voice, as warm as the sun — he has become a third character, assuming the role of the kind of parent he always needed.

“It’s wake up time/Time to open up your eyes/And rise/And shine.” That’s Petty singing to himself again. Self-soothing with the creation of yet another perfect song.