Advertisement

A new compilation of music released on Black Fire Records is a vital link between jazz and go-go, the city’s official genre.

In the mid-1970s, more often than not, the news coming from Washington was dreary. TV screens filled with images of the Watergate hearings, the war in Vietnam and an economy turning cold. But under the shadow of the Capitol, the city’s thriving Black community — making up three-fourths of its population — was in the midst of a renaissance.

Listen to “Soul Love Now: The Black Fire Records Story 1975-1993,” and you’ll quickly get a sense of what it might have felt like to live through some of the headiest years of the Black Power movement in a town also known as “Chocolate City.”

Many compilation albums seem to jerk you around from one artist’s greatest hit to another band’s B-side, but this 10-track anthology feels like a unified dispatch from a shared time and place. It helps that the bands on Black Fire Records often overlapped and traded members, and that the business’s founders — Jimmy Gray, a jazz D.J. and impresario who went by the alias Black Fire, and the saxophonist James Branch, known as Plunky — nudged all their artists to use instruments that reinforced a pan-African sound.

“In terms of African aesthetics, we would judge our music on what it accomplished for the community, for the tribe,” Mr. Branch, 73, said in a recent phone interview from his home in Richmond, Va.

The vocalist Jackie Lewis — who performed for years in Mr. Branch’s band Oneness of Juju, under the name Lady Eka-Ete — said that Mr. Branch treated every performance as a chance to raise awareness. “Plunky’s vision was always to educate people in the music, even to the standpoint of what instruments were being played,” she said in an interview.

“Soul Love Now” comes out of a new agreement between Strut Records and the now-dormant Black Fire label, for which Mr. Branch has controlled licensing rights since Mr. Gray’s death in 1999. Last month, Strut also rereleased “African Rhythms 1970-1982,” a multi-disc selection of Mr. Branch’s recordings with Oneness of Juju. Strut has licensed the entire Black Fire catalog, which includes many albums’ worth of material — much of it never previously released — and is planning further archival releases.

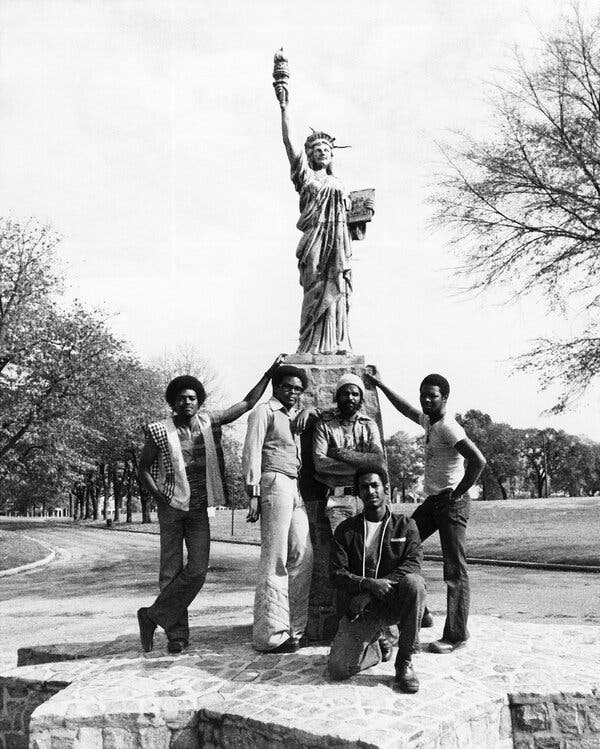

As the 10 tracks on “Soul Love Now” attest, the drum-heavy Afrocentric sound of its artists — including Experience Unlimited, which would later shorten its name to E.U. and grab the nation’s attention in Spike Lee’s “School Daze” — forms a missing link between midcentury jazz and Washington’s go-go tradition, the deep-pocketed style of funk that was recognized this year as the city’s official music genre.

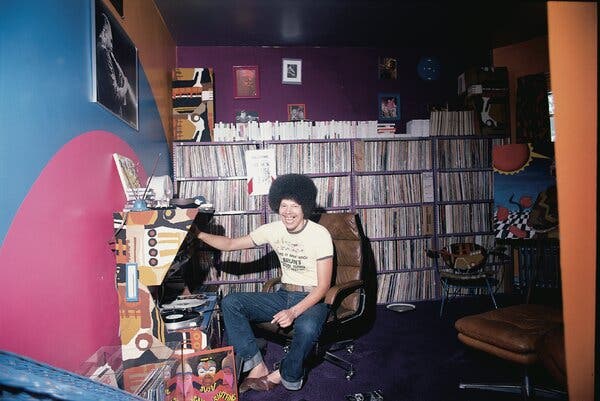

Jimmy Gray was born in D.C. in 1937, into the country’s largest Black professional class and one of its most thriving music scenes. His aunts ran jazz clubs on bustling U Street throughout his childhood, and by the time he was in high school he was already a record nut. After a stint in the Navy he became a D.J. on WHUR-FM, Howard University’s citywide radio station, where he played contemporary jazz on the stylistic cusp. He would rarely interrupt the music to speak, and when he did, his voice was often doused in reverb. Identifying himself simply as Black Fire, he quickly became an invisible icon on the city’s cultural landscape.

Mr. Gray parlayed his influence on the airwaves into promotional jobs with labels, including majors like Verve and small artist-run indies like Strata-East in New York, Tribe in Detroit and Black Jazz in Oakland — outfits that sought to provide a welcoming home for creative musicians in their African-American communities, away from the exploitative practices of corporate labels.

Mr. Branch, then going by Plunky Nkabinde, first learned about Mr. Gray in 1973, when he noticed that an edition of Mr. Gray’s magazine, also titled Black Fire, had used his band’s album art as its cover image. “I thought I was going to sue him, because he used my album cover as his logo,” Mr. Branch said, laughing about it now.

The musicians in charge of Strata-East, which had released Mr. Branch’s album, explained that Mr. Gray was a friend, and an influential one at that. Mr. Gray and Mr. Branch soon became close, and they took particular inspiration from Strata-East. It gave artists the lion’s share of the profits from each release, and allowed them to retain their publishing rights. But Strata-East ran into financial distress — even after scoring a hit record with Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson’s “Winter in America” — leading Mr. Gray and Mr. Branch to wonder if they could create a label that balanced artistic freedom with effective business practices.

They decided that they would institute a clean 50-50 split, whereby the artists and the labels evenly shared the profits from all album sales. “The idea of Black Fire was that of a business undertaking,” Mr. Branch said. “There were some business considerations as well as some cultural considerations.”

He had been working on a new musical concept for his band, swerving away from hard-boiled free jazz toward funkier, more accessible territory. Oneness of Juju made Black Fire Records’ first album in 1975, “African Rhythms.” It never became a hit, but it was a big seller in the D.C. market and has become something of a cult classic.

“Soul Love Now” captures the band performing that album’s title track, a call-and-response anthem with a wriggling groove and a clanging tide of percussion, in 1975. Halfway into the song, with the band really rumbling, Mr. Branch gets on the mic. Backed up by two percussionists, a drummer, a muscly electric bass, male and female vocalists, and the twin chimes of vibraphone and Fender Rhodes, he exhorts the crowd: “Stand up!”

“An African tradition — no spectators, everybody participants,” he declares, then cues the house lights while the music continues to roll.

In these years, the civil rights and Black Power movements appeared poised to take root in a new way in D.C., ushering in an era of progressive Black governance. The city had just achieved home rule in 1973 — the power to elect its own local leaders, who since Reconstruction had been appointed by Congress — and for the first time its large Black middle class was in a position to select its own political destiny.

Charles Stephenson, an activist and educator who managed Experience Unlimited for decades and co-authored “The Beat: Go-Go Music From Washington, D.C.,” remembered that the city government took a hard leftward turn as soon as home rule went into effect — and that Washington’s artistic life reflected that.

“Culture generally imitates life, and at that point in time the Black consciousness movement was in full stride,” he said.

With the Carter-Reagan recession, the influx of crack cocaine and the rise of a conservative national politics, the tides soon changed. But in the sound of “Soul Love Now” is the essence of a city in the midst of a social project that still carries lessons worth hearing.

It’s in the compilation’s opening track, “Children of Tomorrow’s Dreams,” by the radical Black drama troupe Theatre West, its age-of-Aquarius message of change carrying across a hypnotic, Rhodes-driven flow. And it’s in Wayne Davis’s “Look at the People!,” a raucous, secular-gospel cri de coeur.

The compilation’s closing track, “People,” is a grooving but smooth-sailing plea for compassion by Experience Unlimited, which released its debut album on Black Fire in 1977. With only the vaguest hints of the heavily percussive go-go sound that would become its calling card within five years, the tune is as influenced by Seals and Crofts and Santana as by Funkadelic.

Experience Unlimited was far afield from Mr. Gray’s jazz roots, but he was attracted to its unfettered mixing of styles and the social consciousness in its lyrics, Mr. Stephenson said. “Jimmy was a conscience,” he said of Mr. Gray. “He wanted music pure.”

These lessons resonated with Jamal Gray, 33, who took up his father’s mantle and is now a multidisciplinary artist and organizer. He recalls his father raising him in a rich cultural environment that involved more than just radical music-making. “It was just a lot of different moving parts that all represented this raising in communal consciousness,” he said. “The music was a reflection of that.”

On Juneteenth, Jamal Gray’s band, the Nag Champa Art Ensemble, self-released its latest single, “What Would You Have Me Do?,” a stuttering and skewed hip-hop lament. It calls attention to how many things haven’t changed since the late 1970s. There’s frustration in that, but also some reason for hope.