Advertisement

those we’ve lost

His blend of American folk, Latin and rockabilly music captivated listeners worldwide. His secret: arrangements that people could dance to. He died of Covid-19.

By Jim Farber

Trini Lopez, who had worldwide hit records in the early 1960s by creating a unique mix of American folk, Latin and rockabilly music, died on Tuesday at a hospital in Rancho Mirage, Calif. He was 83.

His longtime friend and collaborator Joe Chavira said the cause was complications of Covid-19.

Mr. Lopez’s two biggest records — “If I Had a Hammer” and “Lemon Tree” — had both been hits as well for the folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary several years earlier. But Mr. Lopez’s versions soared even higher on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart.

His “Hammer” reached No. 3 (Peter, Paul and Mary’s had gotten as high as No. 10), and his “Lemon Tree” got to No. 10 (theirs had peaked at No. 35). They also had more international impact.

Mr. Lopez’s version of “If I Had a Hammer” shot to No. 1 in 36 countries and sold more than a million copies. His stylistic advantage? Arrangements that listeners could dance to.

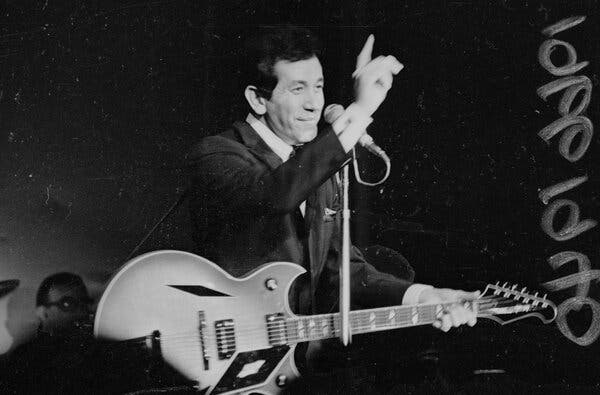

His interpretations bridged two prominent trends of the day. At a commercially rich time for folk music, Mr. Lopez drew on the beauty of the genre’s tunes while souping them up with the sharp rockabilly beats employed by hitmakers like Buddy Holly and Carl Perkins.

“Making songs danceable helped me a lot,” Mr. Lopez told The Classic Rock Music Reporter in 2014, adding, “Discotheques back in those days were not only playing my songs, they were playing my album all the way through.”

For yet another draw, Mr. Lopez punctuated many of his songs with joyous hoots and trills drawn from Mexican folk, emphasizing his ethnic heritage at a time when many Latin performers kept theirs hidden. “I’m proud to be a Mexicano,” he told The Seattle Times in 2017.

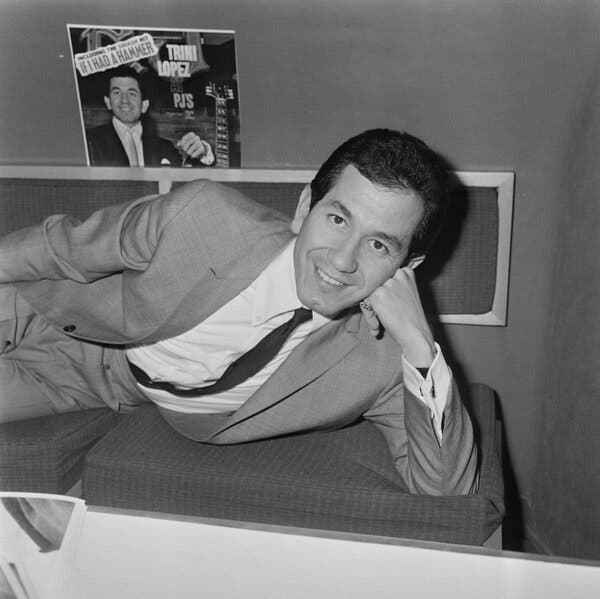

His groundbreaking mix of sounds connected with listeners right from the start, with his debut album, “Live at PJ’s,” recorded at a popular Los Angeles nightclub and released in 1963. The disc went gold, fueled by the success of “If I Had a Hammer.” The album also featured a version of “La Bamba,” the traditional Mexican song that another pioneering Latin rocker, Ritchie Valens, had turned into a Top 40 hit five years earlier.

He racked up other Top 40 hits with “Kansas City” and “I’m Coming Home, Cindy.” He made Billboard magazine’s adult contemporary Top 40 15 times.

Not only a singer, Mr. Lopez was an accomplished guitar player, leading the Gibson Guitar Corporation in 1964 to invite him to design two instruments, both of which became collector’s items. Decades later, star guitarists like Dave Grohl of Foo Fighters and Noel Gallagher of Oasis employed vintage versions of those instruments.

Trinidad Lopez III was born on May 13, 1937, in Dallas. His father, Trinidad II, was a singer, dancer and musician in the ranchera style but made his living as a manual laborer. As a teenager, the elder Mr. Lopez had married Petra Gonzales in their hometown, Morolean, in central Mexico, before moving to Dallas, where they had six children.

The family lived in a poor area of the city known as Little Mexico, where Trini attended elementary school. When he was 11, his father bought him a $12 guitar from a pawnshop and taught him to play. “That was the biggest reward of my life,” he said.

Trini began performing for coins on street corners, playing traditional Mexican songs, including “La Bamba.” At the same time, he took inspiration from the hits of African-American blues artists like T-Bone Walker and Jimmy Reed, as well as early rockers like Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly.

To help support his family, Mr. Lopez dropped out of N.R. Crozier Tech High School (now Dallas High School) in his senior year to play music full time. By then, his music had been increasingly influenced by American-bred styles. His first band, the Big Beats, performed at the upscale Cipango Club in Dallas.

Mr. Lopez later attributed his drive to succeed in part to the prejudice he had endured growing up. “My problem was always being a Mexican in America,” he told the website For Elvis CD Collectors in 2008. “In Texas, we were treated worse than the Blacks. But I had big dreams.”

Mr. Lopez met Buddy Holly, a fellow Texan, in 1958 through local gigs. Holly recommended him to his producer, Norman Petty. But Mr. Lopez’s working relationship with the producer, as well as with his own band at the time, was fraught. Both discouraged his singing. The only two songs that he and his band recorded for Columbia Records were instrumentals.

Frustrated, Mr. Lopez quit the band.

He made his solo debut on the Dallas-based Volk Records with a song he wrote, “The Right to Rock.” The label tried to get Mr. Lopez to hide his ethnicity by changing his last name, but he refused. The next year, he signed with King Records, which issued a dozen singles over the next three years, none of which cracked the charts.

Several years later, after Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P. Richardson, better known as the Big Bopper, died in a plane crash, a Liberty Records producer, Snuff Garrett, contacted Mr. Lopez about possibly replacing Holly as the new frontman of the Crickets. But meetings and auditions never panned out.

Mr. Lopez’s pivotal break came after he landed a steady gig with his trio at P.J.’s, a hangout for stars like Frank Sinatra and Steve McQueen. After catching his show several times, Sinatra sent Don Costa, the key producer for his record label, Reprise, to sign him.

Inspired by the energy of the shows, Mr. Costa had the notion to make Mr. Lopez’s first album a live work, recorded at P.J.’s with just his trio. To capture the full concert experience, Mr. Costa had a microphone on the floor of the club, using as a motif the sound of the audience clapping along to every song.

The “Live at PJ’s” album kicked off with a cover of “America,” from the musical “West Side Story,” emphasizing Mr. Lopez’s Latin heritage, albeit from a Puerto Rican rather than a Mexican perspective. The album included a cover of “Cielito Lindo,” a Mexican classic often performed by Mariachi bands. (Mr. Lopez’s version was heard in 1989 on the soundtrack of the Oliver Stone movie “Born on the Fourth of July,” starring Tom Cruise.)

“Live at PJ’s” proved so successful that it inspired a sequel that same year, “By Popular Demand: More Trini Lopez at PJ’s.” One of its tracks was a cover of the Jerry Leiber-Mike Stoller song “Kansas City,” which went to No. 23 on Billboard’s pop chart.

He soon became a big draw on the Las Vegas circuit as well as in theaters and clubs around the world.

Mr. Lopez found his way into television in 1969, starring in a variety show special for NBC using the surf-rock group the Ventures as his backing band. The show also produced a soundtrack, “The Trini Lopez Show.”

By then he had branched out into acting, with limited success. His first role, in the 1965 film “Marriage on the Rocks,” a comedy with Sinatra and Deborah Kerr, was a cameo in a nightclub, though a song he performed on the soundtrack, “Sinner Man,” reached No. 12 on Billboard’s adult contemporary chart.

He also appeared in the hit 1967 movie “The Dirty Dozen,” in a role that was meant to be large but that got cut down after Mr. Lopez left the shoot before it ended, frustrated by production delays. He had the lead role in “Antonio,” a 1973 movie about a poor Chilean potter who befriends a rich American (Larry Hagman) passing through his village.

Mr. Lopez continued to record albums through 2011, with the “Into the Future” album, for which he paid back Sinatra for his early break by covering songs associated with him.

Mr. Lopez never married and had no children. “I’ve always been a loner,” he told Classicbands.com. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

For all Mr. Lopez’s success as an international headliner, he would later look back with pride at one particular gig in which he shared the bill, with the Beatles, at the venerable Olympic Theater in Paris. It was just before the Beatles’ American debut, in 1964.

“I used to steal the show from them every night!” he told The Classic Rock Music Report. “The French newspapers would say, ‘Bravo, Trini Lopez! Who are the Beatles?’”

Julia Carmel contributed reporting.